Al Jaffee, who contributed cartoons and articles to the satirical Mad magazine for 65 years, died earlier this month at 102. The extraordinary length of Jaffee’s career is shown by his retirement at 99.

The New York Times published a lengthy and affectionate obituary describing Jaffee’s long and interesting life that can be viewed

A Long and Brilliant Career

In 1964, Jaffee created the Mad Fold-In, an illustration on the inside back cover of the magazine which, when folded in thirds, revealed a second image which contained a different, and often subversive, message. Jaffee was the sole creator of the fold-in for 55 years.

A tribute containing 13 of Jaffee’s fold-ins that spanned decades can be seen

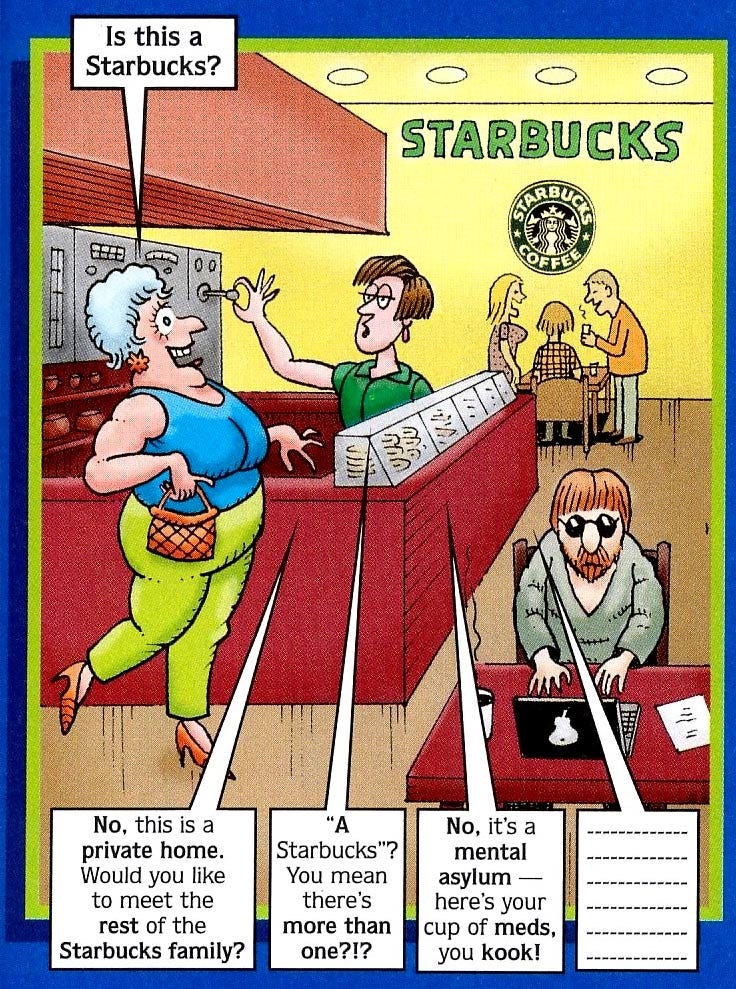

Another of Jaffee’s signature features for Mad was “Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions.” Here is an example:

In Mad’s peak period in the 1960’s and early 1970’s no target was off limits. Mad’s satire and general irreverence seemed incredibly cool to someone growing up in a small town in Michigan. Even better, when I became a Mad subscriber my parents disliked it. My Dad called Mad “juvenile.” I was an aspiring, and then actual, juvenile, so the magazine was a perfect fit.

Here is a 1971 cover showing how Mad went after one of its prime targets, Hollywood movies:

Jaffee was one of the group of artists and writers at Mad that were referred to as “the usual gang of idiots.” He was extremely productive and collections of his work were very popular.

Here is the cover of one of Jaffee’s collections that shows his somewhat beatnik-looking self-portrait:

New York, New York

I drifted away from reading Mad when I went east to Wesleyan University and then to Columbia Law School in New York City. I learned many things living near the Columbia campus on the West Side of Manhattan, and not all of them involved legal training.

I discovered that then, and I think now, it is very difficult to travel from east to west (or the reverse) by public transportation in Manhattan after about 10:00 pm. Busses and taxis go north and south, down Fifth Avenue or up Madison Avenue on the East Side and up and down Broadway or West End Avenue on the West Side, but the crosstown bus routes are limited by the natural barrier of Central Park. The subway lines run generally north and south, except for a shuttle between Grand Central Station and the 42nd Street subway station. And, all forms of public transit run with reduced frequency in the late evening.

The Camera

One weekend night in 1974 or 1975 I went, uncharacteristically, to a party on the Upper East Side. I left the party late, and I was aware that it could take a couple of hours to to get back to our apartment at 114th Street and Riverside Drive, in what was then a dubious neighborhood. The apartment faced two air shafts—there were no exterior windows—and I shared it with two other law students. I decided, in this rare instance, that a taxi, a major expense, was appropriate.

I hailed a taxi and when I got in the back seat I immediately felt something smooth and heavy on the seat—a 35mm camera in its case. Ever respectful of authority, I told the driver, “ Sir, I’ve found a camera in the back of your taxi.” He replied, in the best traditions of New York cab drivers, “I don’t want to f____ ing know about it.”

When I got home, I showed the camera to Al Ferrer, my roommate who had driven a cab in the summer after our first year of law school. His suggested that I call a city agency known as the Hack Commission (from “hackney,” I supposed) and report that I had found a camera. If nobody claimed it, a virtual certainty in a city as big as New York, then I would own a new (to me) camera. I made the call and reported that I had found the camera and where I was when I found it.

About a week later the phone rang in our apartment and a woman’s voice, in a heavy New York accent, said, “I think you have my camera.” The voice described the camera in accurate detail down to the number of exposures and the color of the camera strap. The camera I had appeared to be the one she was describing and I told her so. She said, “Will you bring it to me?” I declined, probably ungraciously. I gave the woman my address which, I suspected, was probably alien territory for her.

Three or four days later there was a knock on the door which I opened to find a stylish New York lady with two of the largest men I had ever seen on either side. My camera claimant had come with personal protection that seemed to have been provided by the New York Giants.

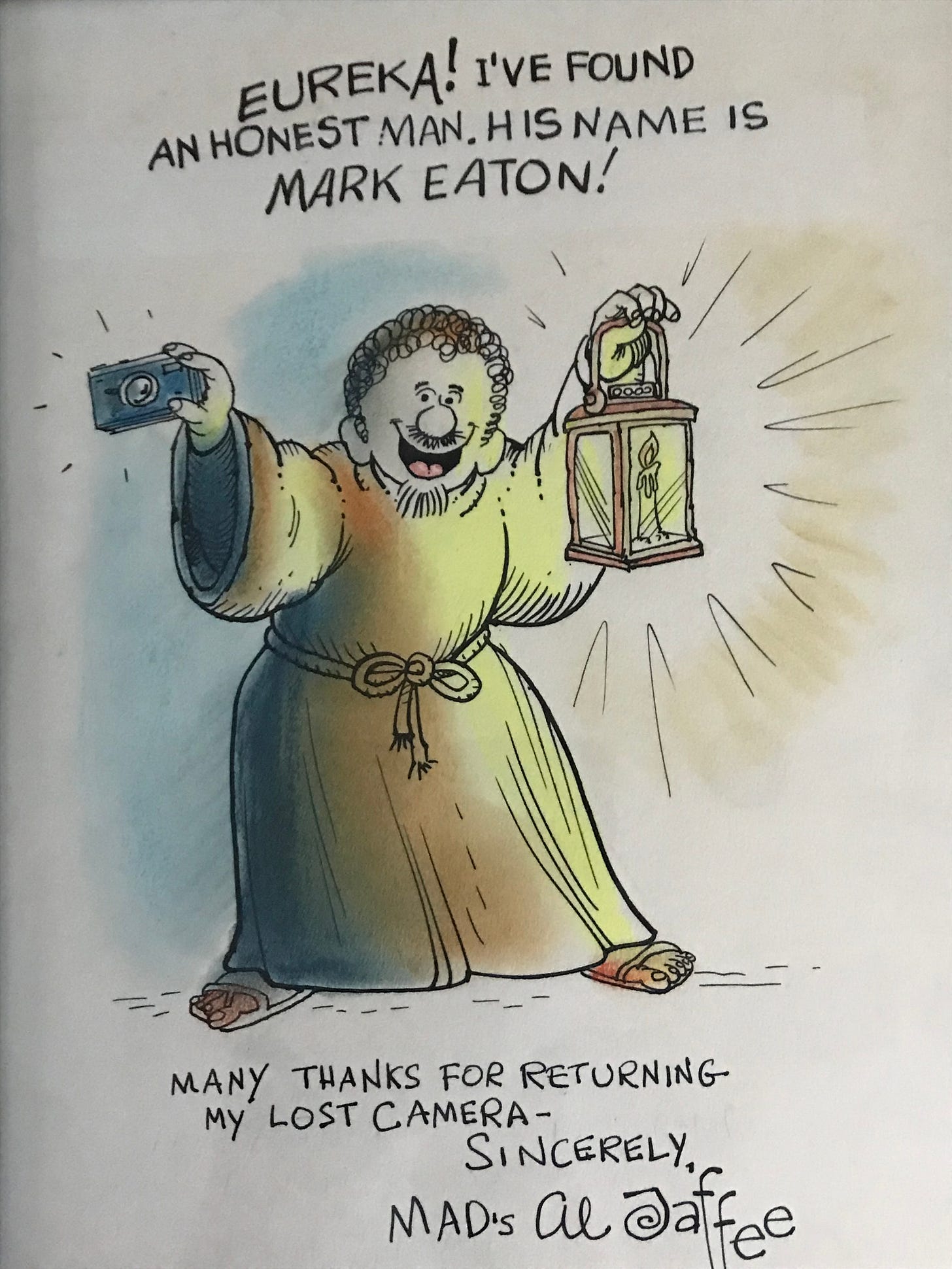

I gave her the camera and the woman said, “You know, it’s not really my camera. It belongs to an artist, Al Jaffee, who draws for Mad. He would like to give you a reward.”

I was too smart to fall for any of this and I was disappointed that my possible acquisition of a fancy camera was not going to happen. I suspected that the woman was a con artist of some kind, but the presence of her two large friends made pursuing that impossible. I adopted my best New York wise guy attitude. “Lady,” I said, “if the camera belongs to Al Jaffee ask him to do a drawing for me.”

Weeks, or maybe months, passed and I forgot about the camera, the lady, and her huge sidekicks.

Then, the mail came one day and this was in it:

Only Al Jaffee would conclude the camera episode with a cartoon self-portrait as the Greek philosopher, Diogenes.1

So, thanks Al, for the many laughs and for shoring up my faith in people.

Diogenes of Sinope (404-323 BCE) was a Greek philosopher best known for holding a lantern (or candle) to the faces of Athens citizens claiming he was searching for an honest man. He rejected the concept of "manners" as a lie and advocated complete truthfulness at all times.

Great story! Jaffe and his irreverent cohorts at Mad Magazine were the “gateway drug” of clever, subversive humor for millions of kids of a certain age.

Only in NYC!