Going to the Movies: Why More Movies Should Be About 90 Minutes Long

Length is not a necessary corollary of movie excellence.

The architect Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, in arguing for a modern and restrained architectural style, famously said, “Less is more.” His point was that there is no automatic correlation between ornament and design quality—a fancier building is not necessarily a superior overall design. The same thing is true of movies: additional length does not automatically create something that is better and more effective than a more concise film.

As silent movies became a mass medium in the early part of the 20th century, American distributors selected 90 minutes as a cut-off point. If a movie was longer, they reasoned, people would either lose interest and leave, or be put off and not bother to see the movie in the first place.

The list of movies that run approximately 90 minutes is impressive. It includes classics such as Frankenstein (1931), This is Spinal Tap (1984), Dr. Strangelove or: How Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and High Noon (1952.)

High Noon and Dr. Strangelove are similar in interesting ways. Each was shot in black and white and each was selected by the Library of Congress in 1989 in the first group of 25 movies to be preserved in the National Film Registry. Each movie was released in an era of widespread anxiety in the United States: concern over the blacklist and McCarthyism for High Noon and Cold War-era fear about nuclear weapons for Dr. Strangelove.

High Noon and Dr. Strangelove: Concise and Effective

In the Oscar-winning (Best Actor, Best Song, Best Editing, Best Score) western High Noon (85 minutes), tense events unfold almost in real time. We first meet Gary Cooper, as Marshal Will Kane, and Grace Kelly as Amy Kane, at their wedding ceremony. Will has retired and they plan to leave their frontier town, Hadleyville, as a new marshal is expected the next day. A telegram arrives at the wedding reception stating that the murderous Frank Miller is on the Noon train. Kane sent Miller to prison five years earlier and he has now been pardoned by corrupt “northern” interests. Three other members of Miller’s gang are waiting at the train depot.

Will and Amy leave Hadleyville, but they turn back because Will cannot abandon the town. One after another, the town’s citizens decline Will’s requests to be deputized to fight the Miller gang. His deputy, Harv (played by a young Lloyd Bridges), who was passed over for the marshal position, abandons him. Kane is in constant motion around the town as he seeks, unsuccessfully, for help in confronting the gang. The continuous action and the numerous shots of clocks heighten the tension.

In the scene above, Will, the agent of the law backed by the threat of violence, is dressed mostly in black. Amy, who is a Quaker, is entirely in white to represent the values of reason and enlightenment. We know then that before their ideal future as a couple can begin there must be a reckoning—a gun fight—with the Miller gang. Amy, of course, is drawn into the fight to protect her new husband.

Legendary film critic Pauline Kael assessed High Noon this way:

The Western form is used for a sneak civics lesson. Gary Cooper is the marshal who fights alone for law and order when his cowtown is paralyzed by fear. Much has been made of the film’s structure (it runs from 10:40 a.m. to high noon, coinciding with the running time of the film); of the stark settings and the long shadows; of screenwriter Carl Foreman’s psychological insight and his buildup of suspense. When the film came out, there were actually people who said it was a poem of force comparable to The Iliad. But its insights are primer sociology and the demonstration of the town’s cowardice is Q.E.D. It’s a tight piece of work though, well directed by Fred Zinnemann.[1]

Kael’s admiration for High Noon is grudging at best: “primer sociology” and “Q.E.D.” suggest that while the movie may be interesting, it is not profound. However, her point that the movie is a “tight piece of work” identifies one of its essential virtues: economy of expression. The movie highlights Cooper’s strength at playing laconic characters. In contrast, Kelly’s challenge was not appear flighty or insignificant and she meets it. The ending in which a split-second gesture (not described here to avoid a spoiler) speaks volumes is consistent with High Noon’s storytelling approach.

You can see the original trailer for High Noon:

Director Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove vaults from an ordinary day to a world-wide nuclear alert when Air Force General Jack D. Ripper, memorably played by Sterling Hayden, goes mad and authorizes his bomber wing to attack the Soviet Union. Ripper’s madness is entirely consistent with Cold War mutually assured destruction deterrent theory. [2]

In this scene, General Ripper orders his bomber pilots to implement “Wing Attack Plan R” to attack the Soviet Union. “R” is the 18th letter of the alphabet which suggests the extent and detail of the Air Force’s planning for nuclear war.

The movie features amazing British comedian Peter Sellers in three widely different roles: Dr. Strangelove (who eerily recalls Henry Kissinger,) the U.S. President (who resembles the late Adlai Stevenson), and Lionel Mandrake, a British officer on General Ripper’s staff who keeps his composure in terrifying circumstances.

George C. Scott’s character, Washington-based Air Force General Buck Turgidson, immediately sees the insane logic of Ripper’s actions to give the United States a “head start” in the inevitable nuclear showdown with the Soviet Union. Scott’s body language and facial expressions suggest that the distance between his portrayal of General Turgidson and his later starring role in Patton was not very great.

Dr. Strangelove was nominated for, and won, numerous awards and gave real meaning to the concept of black comedy. It was seen as a pointed satire of the military and politicians in the United States and the Soviet Union and a commentary on the spiraling arms race.

Kael wrote, "Dr. Strangelove opened a new movie era. It ridiculed everything and everybody it showed, but concealed its own liberal pieties, thus protecting itself from ridicule." [3] This is not completely right: an Air Force bomber flight crew commanded by Slim Pickens as Major T.J. “King” Kong is portrayed as serious, dedicated and competent. When Kong receives Ripper’s orders to bomb the Soviet Union he trades his helmet for a cowboy hat.

Kael also said:

Dr. Strangelove was clearly intended as a cautionary movie; it meant to jolt us awake to the dangers of the bomb by showing us the insanity of the course we were pursuing. But artists' warnings about war and the danger of total annihilation never tell us how we are supposed to regain control, and Dr. Strangelove, chortling over madness, did not indicate any possibilities for sanity. It was experienced not as satire but as a confirmation of fears. Total laughter carried the day. A new generation enjoyed seeing the world as insane; they literally learned to stop worrying and love the bomb. [4]

Regrettably, Dr. Strangelove’s dark charms are relevant today as the war in Ukraine generates discussion (and fear) about the use of nuclear weapons.

The official trailer for Dr. Strangelove can be seen:

High Noon and Dr. Strangelove are stories of crises developing under time pressure. Each is a model of taut and efficient storytelling. The editing in each film is superb. Each cut, or scene transition, is managed with great care and every line of dialogue has meaning. Neither movie contains any waste motion in unnecessary subplots, message-laden speeches, time consuming special effects or other excesses.

Summer of Soul: How to Edit a Huge Quantity of Footage

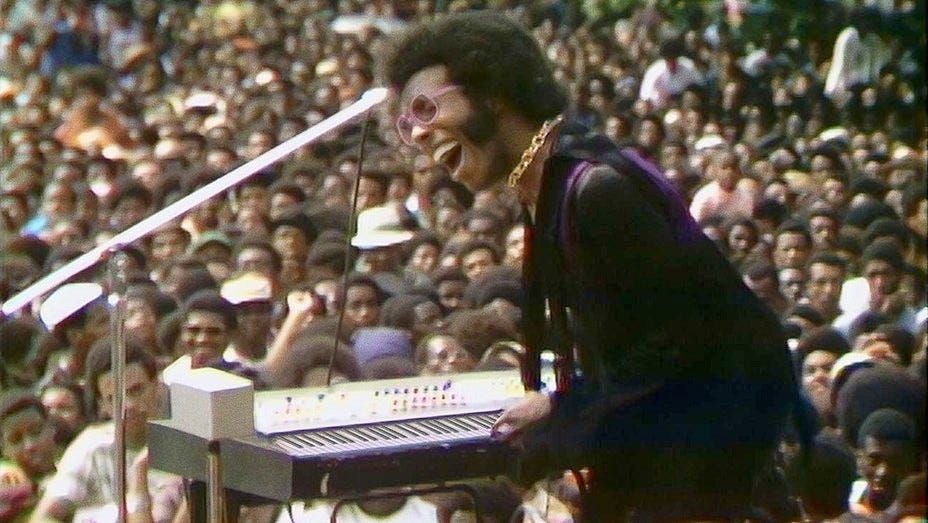

Another example of the importance of movie editing, and how challenging it can be, may be the underappreciated 2021 documentary, Summer of Soul. This Oscar-nominated (Best Documentary Feature) movie focuses on performances and performers at the summer-long 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival that included Sly and the Family Stone, Nina Simone, Mahalia Jackson and Stevie Wonder. Summer of Soul came and went rapidly in theaters. The movie’s director, Ahmir Thompson, a.k.a. Questlove, said, according to The New York Times:

I was like, ‘I got 40 hours’ worth of footage and this has to be 90 minutes,’ he said. I automatically know, after 25 years of doing shows, that if we got 90 minutes, that’s 14 songs. And there’s way more artists than there is space for songs, so now I’m thinking in terms of a cool mix tape.

When the pandemic hit in March 2020, Questlove and his team had to recalibrate. Additional interviews with festival artists were scrapped. He said:

It stopped being just the concert footage once we got to the pandemic and our Jenga fell down. We had to start from the top and be creative.

Summer of Soul, an acute portrayal of New York City in 1969, is much more than a concert movie. It runs a concise 1 hour and 58 minutes.

Licorice Pizza: Subplots of Doubtful Value

If Summer of Soul made rigorous editing a virtue out of necessity, other 2021 movies were not as disciplined. For example, director Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights, Magnolia, There Will Be Blood) released a highly-anticipated coming-of-age movie, Licorice Pizza, set in 1973 in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles where he grew up. The movie clocks in at two hours and 13 minutes.

Portions of Licorice Pizza (the title refers to a defunct Southern California record store that sold vinyl records that looked like, well, licorice pizzas) are devoted to two subplots. In one, Bradley Cooper plays Jon Peters, the supremely egotistical (and insecure) boyfriend of then megastar Barbra Streisand. The other involves Sean Penn as a Hollywood action star staring into the abyss of career decline who performs a drunken motorcycle jump on a golf course to entertain restaurant patrons.

Cooper and Penn are cool guys and sizable stars. It must be gratifying if either wants to be in a movie and it is probably difficult to resist involving either actor if the opportunity presents itself. However, neither subplot contributes much to Licorice Pizza.

The movie is really about how the main characters’ relationship evolves. Gary (played by Cooper Hoffman as about 15) is a child actor who is aging out (and growing out) of film roles. Alana (played by rock musician Alana Haim) is in her mid-20’s and drifting through life. They meet at a yearbook photo shoot at Gary’s school where Alana is a photographer’s assistant. The essence of the story is how Alana and Gary navigate what is, for their time and age group, a massive age difference.

Why Some Movies Are Very Long

Action movie franchises with bankable stars seem to be where “more is more is more” is the rule in movie-making. This trend may be driven by the sheer cost of making a movie with Dwayne (the Rock) Johnson or Matt Damon or Daniel Craig. Another thing that seems to extend action movies is the notion that the quality of the movie-going experience is directly related to the size and number of explosions or car wrecks.

The running time for Craig’s farewell as James Bond, No Time to Die, is 2 hours and 43 minutes, a test for any 007 fan. Again, there are subplots and scenes that could be omitted and little would be lost. Other action franchises can be equally bloated. The Batman, this year’s depiction of events in Gotham City, is a hefty 2 hours and 55 minutes. In these movies screen time consumed in reintroducing old friends (M, Alfred) from earlier movies in the series, subplots and action sequences. The narrative seems less important in these movies than extensive psychic immersion in the world of Bond or the Caped Crusader.

Nobody seems willing to ask how many Batmans we really need. As long as the box office returns hold up for these movies, the answer is probably “More.”

Long movies (examples include Gone With the Wind, Ben-Hur and My Fair Lady) used to have intermissions. Movie intermissions seem to have fallen out of favor, possibly because Hollywood recognizes that audiences are streaming more movies. Streamers can now create their own intermissions of two minutes, two hours or two days in the comfort of their homes.

None of this argues for brevity for its own sake. There are movies longer than 90 minutes in which every scene is essential and compelling. For example, it is difficult to think of scenes in Jane Campion’s 2 hour and six minute psychological thriller/western, The Power of the Dog, or in Sian Heder’s charming 1 hour and 52 minute comedy/drama about a hearing daughter with musical ambitions in a deaf family, CODA, that could have been omitted. Each movie is nominated for Best Picture in this year’s Academy Awards and each is a worthy contender.

The Question

The question, then, for movie-makers, is not that different than that faced by literary creators: What is absolutely necessary to tell the story in the most effective way? More often than is generally realized, the question can be answered in about 90 minutes.

[1] 5001 Nights at the Movies by Pauline Kael. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1982. Q.E.D. is an initialism for the Latin phrase quod erat demonstrandum meaning “which was to be demonstrated.”

[2] Hayden’s time on screen as General Ripper is relatively short, but his portrait of a military leader gone awry is unforgettable. Ripper, in a reference to fluoridation paranoia, drinks only rainwater and pure grain alcohol to avoid polluting his “precious bodily fluids.”

[3] Kiss Kiss Bang Bang by Pauline Kael, Bantam Books, New York, 1969.

[4] Ibid.

I finally got around to reading this on Oscar night. The article was way more interesting than the telecast.

Couldn't agree more. Especially in a world in which moviegoers deem blockbusters under 120 minutes an automatic loss, I feel like the beauty of concise, short but sweet films is lost beneath a bloated status quo of film. And while I really liked Licorice Pizza, I agree that there were many points that should've just been cut.