Why New York Times v. Sullivan Still Matters

Justice Clarence Thomas, Professor Herbert Wechsler and the origins and future of a pivotal Supreme Court decision

Supreme Court justices can be at their most interesting when they write not about the case before them, but about cases they would like to decide and how they would decide those cases.

On October 10, the Court denied a petition for a writ of certiorari in a defamation case, Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC. Certiorari refers to the Court’s discretionary jurisdiction—cases it is not required to hear but can elect to decide. Defamation is a tort that derives from the publishing of a false statement of material fact that harms the plaintiff’s reputation.

Justice Clarence Thomas concurred in the denial of certiorari and wrote a separate concurrence urging the Court, as he has previously, to review (for the purpose of overruling or modifying) New York Times Co v. Sullivan, the 1964 case that established the standard a public figure must meet to recover damages for defamation. [1]

Thomas’ short concurrence can be read

What New York Times v. Sullivan Means

New York Times v. Sullivan addressed the tension between the law of defamation and the free speech and free press guarantees of the First Amendment.

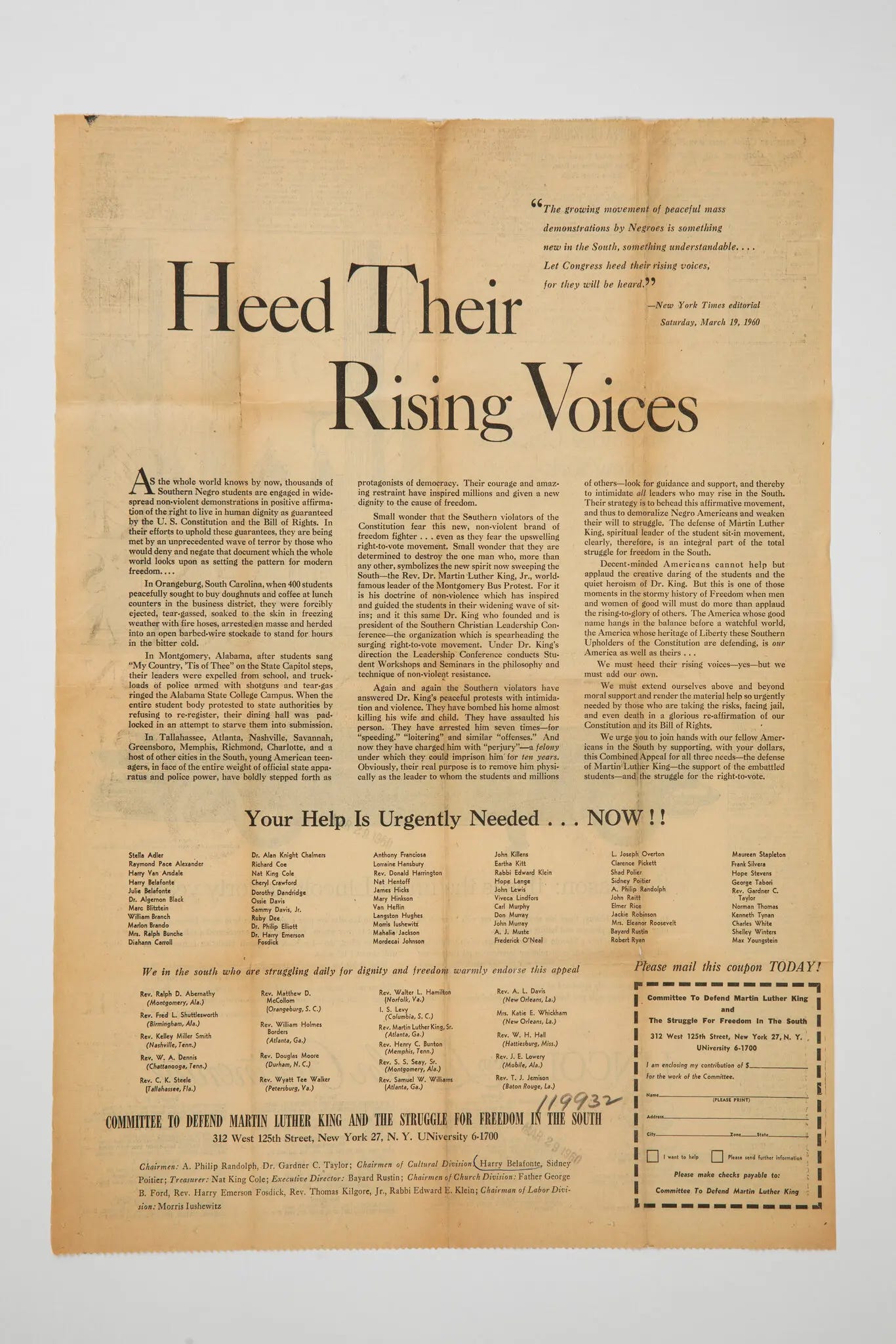

In 1960, the Times published a full-page advertisement that included the names of prominent civil rights activists, including actors and ministers. The advertisement, or advertorial, titled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” sought financial support for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who had been accused of violating various Alabama laws. The advertisement was paid for by local clergy who described themselves as the “Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South.” Here is a replica of the advertisement:

“Heed Their Rising Voices” contained factual inaccuracies relating to student expulsions, the number of times Dr. King had been arrested, and indirectly implied that the police were involved in the bombings at Dr. King’s home.

L.B. Sullivan, a Montgomery, Alabama city official was not mentioned in the advertisement. Sullivan was the head of the city’s public safety agency and he argued that the criticism of the police damaged his reputation.

At that time, the Times’ average daily circulation in Alabama was less than 400 copies, or less than 1% of its overall circulation.

A jury took less than two hours to award $500,000 in damages, or over $4 million in today’s dollars, to Sullivan. The jury award was the largest of its kind in Alabama history. The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed the award.

The Supreme Court, in a 1964 opinion by Justice William Brennan, reversed the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision. The opinion can be read

Justice Thomas states in his concurrence that New York Times v. Sullivan articulates a constitutional standard that:

…prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood unless he proves that the statement was made with ‘actual malice’—that is with knowledge that was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.

More explicitly, a public official plaintiff must prove that the defendant’s alleged statement was false and was of the type that would lower the plaintiff’s reputation. The statement must be a fact (as distinct from opinion) and the plaintiff must prove that the defendant published the statement knowing that it was false or published it with a “reckless disregard of the truth.”

Thus, the New York Times v. Sullivan standard allows journalists to be sloppy, or negligent, in reporting on public figures. Facts that permit a judge or jury to find that a defendant knew that what was being published was false, or had doubts about its veracity, are usually very hard to find.

Herbert Wechsler: Lead Counsel in New York Times v. Sullivan and Columbia Law School Professor

I was very naïve when, at age 21, I entered Columbia Law School in the fall of 1972. Even so, I learned quickly that there was something special about Professor Herbert Wechsler. The student and faculty foot traffic in the hallways of the law school seemed to part in respect when Wechsler appeared. [2]

Everyone at Columbia knew that Wechsler, who was lead counsel for the Times in New York Times v. Sullivan, was not just another academic—he was also a practicing constitutional lawyer of formidable ability.

L.B. Sullivan’s case was a major threat to the Times’ core business and reason for existing. There were other lawsuits pending or threatened that arose out of the “Heed Their Rising Voices” advertisement or other articles that portrayed the behavior of southern officials in unflattering ways. National media organizations, including the Times, cut back on sending reporters to the Deep South. The Times hired Wechsler, who had extensive experience in Supreme Court cases.

Wechsler spoke to our Constitutional Law class as a professor and as a lawyer who had been active in high stakes constitutional issues. Among other cases, Wechsler successfully represented the government in Korematsu v. United States, the case that upheld the Roosevelt Administration’s internment of Japanese citizens during World War II. Korematsu is not seen as the Supreme Court’s finest hour.

In a 2014 law review article, 50 years after the New York Times v. Sullivan decision, Wechsler’s handling of the case was described this way:

All these facts played a role in the case, but the most important force was the vision of Herbert Wechsler, the lawyer who argued the case for the Times in the Supreme Court. He broadened the issues beyond the necessities of the case to achieve his vision of what the law ought to be. He wanted to do more than win the case; he wanted to remake the law of libel. In doing so, he showed how much a committed, learned, and skilled advocate can achieve. [3]

Wechsler, if prompted, would talk about the case in class and how worried the Times was about the case. The paper’s leaders were also confounded, or maybe appalled, about the environment that contributed to L.B. Sullivan’s victory over the paper in the Alabama courts.

Wechsler had no special expertise in defamation law when the Times hired him. His masterstroke may have been his argument that the Supreme Court should hear the case. Lawsuits against public figures were common in colonial times. Until New York Times v. Sullivan, the free press and speech provisions of the First Amendment were not considered relevant to the state law of defamation.

Wechsler argued that the Supreme Court should hear New York Times v. Sullivan because the Alabama defamation law, which was similar to the law of many other states, was on these facts a form of seditious libel. In England, and to a lesser extent in colonial America, the common law made criticizing the government a crime by classifying such criticism as sedition.

In 1798, Congress passed the Sedition Act which made it a crime to publish “false, scandalous and malicious” accusations against the federal government, the president or Congress. The law expired in 1801 and was widely seen as an unconstitutional violation of the First Amendment.

Thus, Wechsler, at least initially, bypassed arguments relating to the inherent justice of the Civil Rights movement or the First Amendment’s guarantees of free speech and a free press. Instead, he found a compelling and impeccable reason grounded in principles that went back almost to America’s founding to convince the Supreme Court to decide the case.

Dominion Voting Systems v. Fox News and New York Times v. Sullivan

The standard articulated by the Supreme Court in New York Times v. Sullivan was an essential part of Fox News’ defense in the defamation case brought against Fox by Dominion Voting Systems that settled earlier this year. Facts came out in discovery that showed numerous examples of Fox reporters and editors doubting the veracity of the “news” it was reporting after the 2020 presidential election. This extended up the corporate chain of command all the way to Fox’s top executive, Rupert Murdoch. It became evident that Dominion’s evidence would likely meet the New York Times v. Sullivan “reckless disregard” standard. Fox paid a remarkable $787.5 million to settle the case, the largest amount ever paid by a defendant in a defamation case.

Walter Olson of the generally conservative Cato Institute summarized how the Dominion/Fox case related to New York Times v. Sullivan this way:

You sometimes hear people talk as if even plaintiffs with meritorious cases can’t win libel suits in American courts because of the First Amendment protections of the Supreme Court’s 1964 New York Times v. Sullivan case. Not so. Today’s settlement, in which Fox has reportedly agreed to pay Dominion Voting Systems a handsome $787.5 million, shows that while Sullivan may be speech‐protective, it did not then and does not now eviscerate common law rights to sue for defamation.

The media landscape looks very different today than it did in 1964. Has New York Times v. Sullivan made it too hard for public figures to win defamation cases? Justice Thomas thinks so.

Why Justice Thomas Wants the Court to Overrule New York Times v. Sullivan

Libel Law in 1787. Justice Thomas’ concurrence argues, “The common law of libel at the time the First and Fourteenth Amendments were ratified did not require public figures to satisfy any kind of heightened liability standard as a condition of recovering damages.” He asserts that in New York Times v. Sullivan the Court “usurped” control over state defamation laws and imposed its own elevated standard.[4]

Thomas sees New York Times v. Sullivan, and the cases extending it, as “policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law” that bear, “no relation to the text, history, or structure of the Constitution.”

Thomas’ argument reveals the inherent limitations of “originalist” jurisprudence bound so tightly to history. The First Amendment was adopted in 1791 when the United States was a pre-digital nation. The media did not have nearly the reach and influence, or the capacity to inflict reputational harm, that it had in 1964 or that it has today. Thomas’ approach seems to require that the makers of the Constitution exercise a kind of clairvoyance. If the Constitution’s framers did not consider how state defamation law intersected with the First Amendment it was because the issue was not a material practical concern in their era.

Justice Thomas as a Media Figure. Thomas’ concurrence asserts that “the actual-malice standard comes at a heavy cost” because media organizations and interest groups can safely “cast false aspersions on public figures with near impunity.” The Supreme Court has a “rule of four” that requires four justices to vote to hear a case. Whether three of his Supreme Court colleagues will accept one of his repeated invitations to hear a case challenging New York Times v. Sullivan remains an open question.

Thomas’ concurrence in Blankenship v. NBCUniversal, LLC cites several cases in which he advocated, consistent with his originalist view of the Constitution, that the Court review New York Times v. Sullivan. [5] Even so, it seems fair to ask whether the “heavy cost” that Thomas sees as a problem may also be driven by his perceptions of the media accounts of his acceptance of, and failure to report, gifts from wealthy friends.

For example, on October 25 The New York Times described a report by Democratic members of the Senate Finance Committee. The report found that Thomas acquired a $267,230 luxury motor coach through an interest-only five year loan with no down payment from a wealthy friend. The loan was ultimately forgiven. The Times story can be read

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] The written form of defamation is called libel. The oral form is known as slander.

[2] Another professor I knew at Columbia who became well known for achievements outside teaching and scholarship was Ruth Bader Ginsburg. When I took her seminar on Conflicts of Laws (an arcane subject of limited practical utility) Ginsburg was bringing a series of Supreme Court cases on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union that resulted in major changes to the Social Security laws. She talked in class about one of them, Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld. Mr. Wiesenfeld was a widower whose wife died in childbirth. He wanted, unusually for that era, to raise his daughter as a stay-at-home father. His claim for Social Security spousal death benefits was denied. Women, in Congress’ view when the law was passed, would not be breadwinners and would need death benefits if their husbands died. Men, under the law as then written, had no right to death benefits if a spouse died. The Supreme Court, as Ginsburg argued, ruled that the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment required that men have the same rights to spousal death benefits as women.

[3] For a deep dive into how Wechsler handled the New York Times v. Sullivan case, see Wechsler’s Triumph, by David A. Anderson, 66 ALA. L. Rev. 229, 230. The article can be read

[4] The theme that a Supreme Court precedent should be overruled because it “usurps” control of legal issues that belong to the states was evident in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the 2022 case that overruled Roe v. Wade. Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion called Roe “egregiously wrong.”

[5] In his concurrence, Justice Thomas cites himself several times. Borrowing this approach, see a May 24 post in About Alexandria’s Legal Affairs section titled, Say it ain’t so, Justice Thomas.

Special thanks to David Logan for assistance with this post.