Why Lincoln Still Matters

Three Fascinating Books Show the Differing Political Styles of Abraham Lincoln and Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin

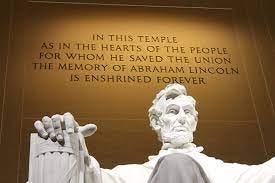

Governor Youngkin’s Vetoes

The Virginia General Assembly’s recent legislative session concluded with Governor Glenn Youngkin signing some bills and vetoing others. Virginia’s governors customarily sign both the House of Delegates and Senate versions of bills that are identical when they reach the governor’s desk. The Richmond Times-Dispatch reported on April 12:

GOP Gov. Glenn Youngkin vetoed nine out of 10 bills sponsored by a Democratic state senator whose bills were threatened during the legislative session by a senior aide to the governor.

Ten bills filed by Sen. Adam Ebbin, D-Alexandria, reached the governor’s desk. Youngkin amended one and vetoed the other nine.

“I’m stunned at the governor’s unexplainable decision to veto meaningful, non-controversial, legislation. It is the polar opposite of what he campaigned on,” Ebbin wrote on Twitter.

Four of the nine bills passed the House and Senate without any opposition. Asked why he vetoed the bills, Youngkin spokeswoman Macaulay Porter issued a statement that cited companion bills in the House for a number of Ebbin’s bills.

In other words, because the same bill passed the House, Ebbin’s bill wasn’t needed. However, governors traditionally sign a bill if they agree with the policy, even if there’s a companion bill. No other lawmaker’s bill was vetoed for that reason even though many bills have companions in the other chamber.

Ebbin, who chairs the Senate’s Privileges & Elections Committee, told me that he attributes the vetoes to his successful opposition to Youngkin’s nomination of Andrew Wheeler as Secretary of Natural Resources. Wheeler, formerly a lobbyist for fossil fuel interests, was the Trump Administration’s Environmental Protection Agency Administrator.

Ebbin said that he could see no public or legislative purpose for the vetoes of the nine bills and that the Youngkin administration has not explained the reasons for the vetoes.[1] Ebbin could not recall anything like the vetoes happening previously. Accordingly, the vetoes appear to be an attempt at payback.

Today’s Question

Governor Youngkin’s vetoes of Senator Ebbin’s bills might be viewed in light of this question: What would Abraham Lincoln have done? That is, would Lincoln have retaliated against a political rival as Governor Youngkin did?

Character and political style are intertwined. Politics does not build character; it reveals character. There may be more written about Lincoln, and his character and political style, than any American president.[2] Lincoln’s approach to politics can be instructive.

The following is a short admiring account of three illuminating books about the 16th president and how he conducted politics. Collectively, they suggest an answer to today’s question about Governor Youngkin’s vetoes.

Lincoln as Political Leader

Economics nerds (and others) will enjoy Roger Lowenstein’s new book, Ways and Means—Lincoln and His Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War. (Penguin Press, New York, 2022.) This book makes the case that, rather than seeking to punish his political rivals as Governor Youngkin did with his vetoes, Lincoln found ways for them to contribute to his agenda.

Ways and Means shows Lincoln enabling his political rival and Treasury Secretary, the hardworking, capable, ambitious and politically obtuse Salmon P. Chase. Lincoln, in the shrewd pursuit of his goals, generously accommodated Chase’s emotions and ego and found ways to maximize Chase’s considerable abilities as a financial engineer. Chase was convinced that he, not Lincoln, should have been president and he showed his conviction in numerous ways. [3]

Lincoln’s management of Chase, and others in his cabinet, accelerated the nation’s transition from Thomas Jefferson’s vision of decentralized, or state-based, economic and government authority to Alexander Hamilton’s concept of a strong and effective federal government.

In making the case about the importance of economics in waging war, Lowenstein gives credit where it is due:

Given its economic and demographic disadvantages, the South’s stick-to-itiveness, militarily, was nothing short of remarkable. ‘The Yankees did not whip us in the field,’ one Confederate leader said. ‘We were whipped in the Treasury Department.’ (p. 207)

Lincoln deftly and selflessly managed Chase, and others in his administration, including a rotating cast of generals before he settled on U.S. Grant. His goal, of course, was to preserve the union.

Lincoln as Intellectual Revolutionary

Garry Wills, a prolific and insightful historian, won the 1992 Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for Lincoln at Gettysburg—The Words That Remade America (Simon & Shuster, New York, 1992).

Wills meticulously analyzes the 272-word Gettysburg Address beginning with an overview of the traditions of Greek funeral oration.[4] He demolishes the myth that Lincoln composed the Address while traveling to the ceremony and explains why it was revolutionary in thought and style. Here is Wills examining Lincoln’s artistry:

Some have claimed, simplistically, that Lincoln achieved “down-to-earth” style by using short Anglo-Saxon words rather than long Latin ones in the Address. Such people cannot have read the Address with care. Lincoln talks of a nation “conceived in Liberty,” not born in freedom; of one “dedicated to [a] proposition,” not vowed to a truth; of a “consecrated” nation whose soldiers show their “devotion”—Latinate terms all. (p. 174)

One of the many astonishing things about the largely self-educated Lincoln is that we know he was the principal author of his enduring writings—he had no staff of speech writers and pollsters. The succinct Gettysburg Address contrasts markedly with the two hour oration of more than 13,000 words delivered by Edward Everett, the principal speaker at the ceremony. [5]

Wills argues that, “Words were weapons, for him, even though he meant them to be weapons of peace in the midst of war.” Wills asserts:

This [the Address] was the perfect medium for changing the way most Americans thought about the nation’s founding acts. Lincoln does not argue law or history, as Daniel Webster did. He makes history. He does not come to present a theory, but to impose a symbol, one tested in experience and appealing to national values, with an emotional urgency entirely expressed in abstractions (fire in ice.) He came to change the world, to effect an intellectual revolution. No other words could have done it. The miracle is that these words did. In his brief time before the crowd at Gettysburg he wove a spell that has not, yet, been broken—he called up a new nation out of the blood and trauma. (p. 175)

In the Gettysburg Address Lincoln outlined a future for a single nation with common principles, not the subjugation of a victorious region over a defeated one.

Lincoln as Chief Executive

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address is carved into the marble wall of the Lincoln Memorial.[6] Ronald C. White examines the 703-word Second Inaugural in Lincoln’s Greatest Speech—The Second Inaugural (Simon & Shuster, New York, 2002.) Lincoln delivered the Second Inaugural about 15 months after the Gettysburg Address and about a month before he died.

The Second Inaugural was neither celebrated victory nor a condemned the South for the sin of slavery. Instead, Lincoln described a shared responsibility for the war. He highlighted commonalities (“Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other”) not divisions. The Second Inaugural articulates a magnanimous approach to southern citizens and a positive future for the nation, not just part of it. Here is the closing paragraph:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace among ourselves, and with all nations.

Frederick Douglass said that the Second Inaugural sounded more like a sermon than a state address. [7]

White shows Lincoln laboring over the Second Inaugural Address. He sought and incorporated comments and suggestions from others, including his Secretary of State, William Seward. The final version was magisterial on the page and in spoken form.

What Can We Take Away?

Lowenstein’s Ways and Means shows Lincoln as the consummate manager who worked with his political rivals to preserve the union and, ultimately, abolish slavery. Lincoln was so secure as a person and a politician that he could overlook personal slights and, in some members of his cabinet, a seeming lack of that most highly prized value of today’s political environment: loyalty. [8]

Wills in Lincoln at Gettysburg and White in Lincoln’s Greatest Speech show Lincoln as a largely self-taught writer of towering ability and achievement. His attention never strayed from the largest issues: saving the union and inspiring the nation in writings articulating heartfelt expressions of national reconciliation.

Each of these books, and Lincoln’s writings, reveal a political leader who did not engage in payback. Instead, the books show Lincoln as a politician with a distinct largeness of spirit. Lincoln was a complex person, but there is very little evidence that he was petty.

The answer to today’s question about Governor Youngkin’s vetoes—What would Abraham Lincoln have done?—seems reasonably clear.

Your comments are very welcome.

1. According to Ebbin, of his nine bills vetoed by Youngkin, six were identical to bills passed in the House of Delegates. Judged by their titles and summary descriptions, the bills are largely good government measures, for example, “SB311 Homebuyer Protections—Codify a duty for real estate licensees to disclose to other parties in the transaction any ownership interest or pending legal action” or “SB278 Electric Vehicle Parking—Allows localities to ticket non-electric vehicles that are parked in electric vehicle charging stations.”

2. Lincoln is always with us. May 30 is the 100th anniversary of the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall which is visited by over 5 million people every year. There are countless informative and entertaining books on Lincoln and his presidency. David Herbert Donald won the Pulitzer Prize for his very readable biography, Lincoln (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1995.) Doris Kearns Goodwin’s justly acclaimed Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln (Simon & Shuster, New York, 2006) shows Lincoln adroitly managing the members of his talented but egotistical cabinet, including William Seward and Salmon P. Chase. Historian and novelist Richard Slotkin’s novel Abe: A Novel of the Young Lincoln, is a particularly enjoyable imaginative take on Lincoln in his youth.

3. Chase authorized government borrowing at unprecedented levels and created economic innovations that contributed to the North’s victory. These changes now seem to be part of the natural order, for example, a central government-issued currency usable as legal tender for debts and obligations, a system of federally-chartered national banks and an income tax that was successfully implemented in a country that loathed taxation. Ways and Means explains how Chase’s financing exploited the North’s liquid assets—the result of a manufacturing base, trade and finance—as distinct from the South’s fixed assets: land, cotton and slaves. The North’s successful embargo of the South’s cotton exports meant that it had almost no way to pay for the war. Lowenstein’s explanation of the Confederacy’s success in getting British investors to buy cotton-backed bonds redeemable at the successful conclusion of the war is almost hilarious. Other chapters highlight the importance of the Treasury’s wily government bond placement agent, Jay Cooke. We also meet forgotten heroes, for example, Representative Justin Smith Morrill of Vermont who was unhappy about his inability to pay for college during the war. He introduced legislation to establish the system of land grant colleges that endowed universities for middle class Americans.

4. Lincoln wrote out five copies of the Gettysburg Address, two before the ceremony, and three afterward. They differ in minor respects. Here is the generally accepted version of the Gettysburg Address:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate - we cannot consecrate - we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled, here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here.

It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us - that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion - that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

5. There seems to be no picture of Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address. In the 1950’s this picture surfaced which appears to show Lincoln getting down from the platform. This suggests that Lincoln’s speech was so brief that the photographs present did not have the time required to set up their cameras.

6. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address

Fellow countrymen, at this second appearing to take the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention, and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil-war. All dreaded it -- all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war -- seeking to dissolve the Union, and divide effects, by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!" If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope -- fervently do we pray -- that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether"

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan -- to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

7. White explains Lincoln’s gift of creating language that worked on the page and in a speech:

Lincoln’s writing resembled poetry in part because he was writing for the ear. Lincoln sometimes gave a primary accent to syllables that ordinarily would have received secondary stress. Listen to or say aloud the meter of these words, accenting the syllables in italics:

Fond-ly/ do we hope

Fer-vently/ do we pray

That this might-ty scourge/ of war

May speed-i-ly pass/ a-way

Liberties can be taken in poetry that one ordinarily would not take in prose.

We also hear Lincoln’s fondness of repetition and balance again. The Second Inaugural offers plentiful examples.

do we hope—do we pray

drawn with the lash—drawn with the sword

as was said—must be said

8. For a demonstration of the importance of loyalty in today’s politics, consider Republican Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) who appears, as a matter of loyalty, to have lied about telling the truth. More details are available in a recent account by David A. Graham in The Atlantic.

Thanks again Mark for another interesting piece.

I never tire of reading books about Lincoln as he is/was an endlessly fascinating person. When Doris Kearns Goodwin was writing her great book on Lincoln, one of her research assistants, Nora Titone, was sent to New York to do some research on the Booth family. What she found was incredible and was nearly lost to history. She was given access to never before seen Booth family papers, including correspondence and diaries.

She discovered that John Wilkes Booth's grandfather, Junius, was considered the greatest Shakespearean actor of his time. When he died, John Wilkes and his older brother Edwin vied to replace him. Edwin rose to prominence, acting often at Ford's Theatre, where he would get his younger brother lesser roles, which divided the brothers, but also explains how John Wilkes Booth was very familiar with Ford's Theatre and knew how to get in and where to go on the night of the assassination. Eventually the two brothers divided up the country, Edwin taking the North and John Wilkes the South, where it is believed his Southern sympathies were nurtured. Edwin became incredibly rich and famous, lived in New York, built The Booth Theatre, and became the president of The Players, the most prominent social club of its time.

Nora Titone relays all of this information to Goodwin, who tells her that what she has found is incredible and is deserving of its own book, so Nora Titone wrote My Thoughts Be Bloody, which I strongly recommend.

Those 3 all sound like good books and ones I should read. You refer to "Team of Rivals," which is superb. The comments about fellow cabinet members are interesting. As I recall from Team of Rivals, EVERY Cabinet member thought he should be President instead of Lincoln (who they all felt was a baboon). Seward was the earliest to realize that Lincoln had some remarkable talents, and Seward became Lincoln's most loyal supporter. But the comments in your note about Chase apply equally to Stanton. Stanton was less of a political rival, but as a young lawyer Lincoln represented a railroad, and was reporting to Stanton. Stanton was in the "big city:" Cincinnati. Lincoln made the pilgrimage to Cincinnati, where he got to cool his heels in the waiting room for an inordinate time. Stanton basically treated him like dirt. 10-15 years later Lincoln was President. He was trying to figure out who to name as Secretary of War to replace Simon Cameron (who had definitely been a political rival). Stanton was not a political rival; he had served very briefly as Buchanan's AG and then advised Cameron, but there were certainly splits in the Lincoln Cabinet as to whether Lincoln should appoint him. Lincoln decided Stanton was the right man for the job. There is no question Lincoln remembered the humiliating encounter in Cincinnati (what human being wouldn't remember?) but Lincoln decided it was more important to get the right man for the job. How many Presidents would have done that? Trump's obsession with personal loyalty is clearly above and beyond, but it's a rare politician who can ever forget such insults. Lincoln could.

The continuing question I have about Lincoln: if he had not been assassinated, how would Reconstruction have turned out? We'll never know, but Andrew Johnson set a low bar and Lincoln surely would have been better. Grant had his own issues, but Johnson's actions (and inactions) limited what Grant could do. Would all of today's "racist" issues have been solved? Likely not--but I contend things would have been better. Slavery was the stain on America that keeps on giving; Reconstruction was our best chance to deal with the stain, but the opportunity was missed. The whole issue would have been an enormous challenge, but if anyone could have led the way, it was Lincoln.