Literary Dude: Wendell Berry Calms Things Down

Two poems by the Kentucky poet and farmer

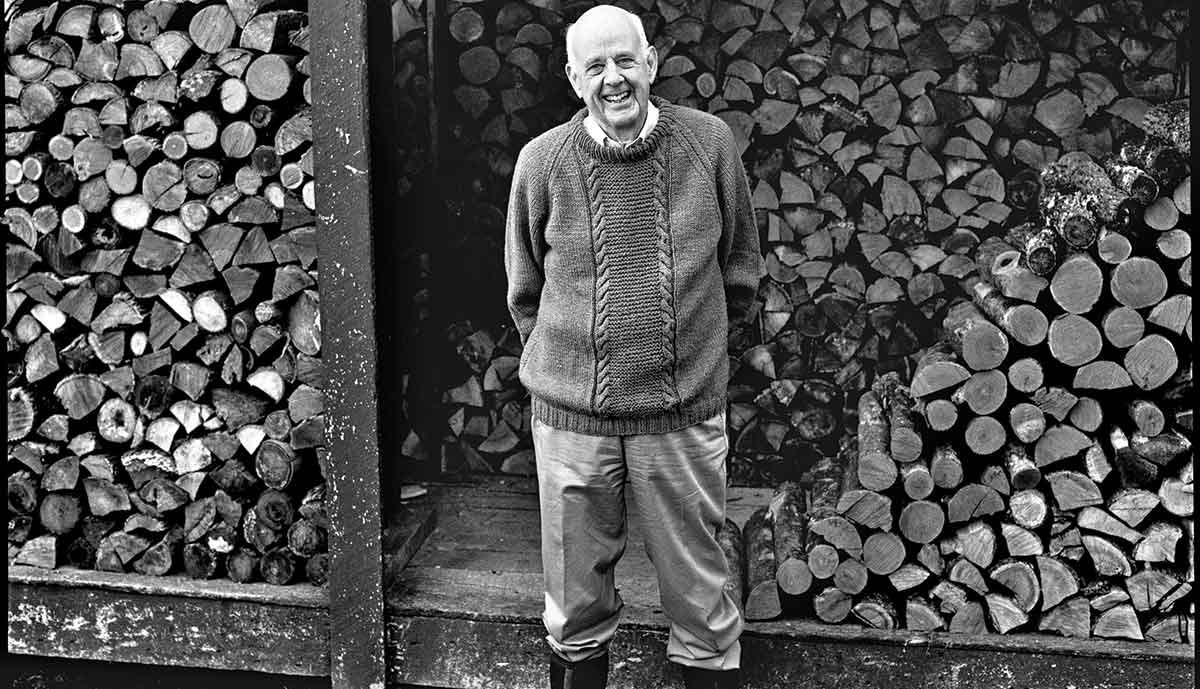

Wendell Berry, 89, is a poet, novelist, short story writer, essay writer, and advocate.

Berry has a long history of commitment to a variety of causes. He was vocal in his opposition to the Vietnam War, against the death penalty, and against mountain top removal coal mining. Berry’s activism includes opposition to large-scale agribusiness.

Berry was born in Henry County in north central Kentucky. Berry has lived and farmed in Port Royal, Kentucky since 1965. He is the author of numerous volumes of poetry and essays, and has won many literary awards.

Berry’s stature as a poet, and his personal appeal and authenticity, have led to numerous profiles including one in The New Yorker in February 2022. It can be seen

If the world sometimes seems to be on fire, Berry’s poetry is a refuge.

Here are two of Berry’s short poems that are worth thinking about as 2023, a difficult year, comes to an end.

The Peace of Wild Things

When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.—1968

Here is a video of Berry reading the poem:

“The Peace of Wild Things” was the title poem in a collection that Berry published in 1968. In a year of tragic deaths (Robert F. Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.) Berry found solace and peace, “…where the wood drake/ rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.”

English teachers talk about diction, or word choice, in poetry. Berry choses his words very carefully. A drake is a mature male duck—this graceful word adds to the poem’s simple elegance and confirms the speaker’s familiarity with nature. The speaker knows exactly what he is looking at when he sees the drake.

Similarly, the speaker describes the heron as “great,” evoking a heron’s majestic stillness and deliberate gait in a wetland. The greatness of the heron goes beyond its possible identity as a great blue heron, a specific species.

The power of the poem is in the intensity of the speaker’s personal impressions. The repeated pronoun “I”, and the active voice, invite a sharing of the those experiences: “I wake” and “I go and lie down” and “I come into the peace of wild things” and “I come into the presence of still water” and “I feel above me the day-blind stars” and “I rest in the grace of the world.”

The breaks in the 11 lines of the poem emphasize the most important words and ideas at the end of each line: “me,” “sound,” “be,” “drake,” “heron feeds,” “wild things,” “forethought,” “still water,” “blind stars, “a time” and “am free.” The sequence of these words is very nearly another poem.

Berry is that rare artist willing to express his flawed humanity while acknowledging his gifts. That remarkable juxtaposition is on view in this poem:

A Warning to My Readers

Do not think me gentle

because I speak in praise

of gentleness, or elegant

because I honor the grace

that keeps this world. I am

a man crude as any,

gross of speech, intolerant,

stubborn, angry, full

of fits and furies. That I

may have spoken well

at times, is not natural.

A wonder is what it is.—1973

Five years later, Berry published a collection of poems called The Country of Marriage, that contained “A Warning to My Readers.”

This 11-line poem, with lines of no more than five words each, is a marvel of concise expression. Berry, in an act of rare artistic humility, disclaims moral or personal superiority and aligns himself with us, his flawed readers.

In Joan Didion’s essay Why I Write (a titled borrowed from George Orwell) she explained:

In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions—with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating—but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.

Wendell Berry intrudes on our “most private space” as readers with full disclosure and special courtesy.

“A Warning to My Readers” also acknowledges that the debate, or process, of distinguishing an artist’s personal qualities from the meaning and effect of his or her art will never be finally resolved. Poets, painters, singers, and others—many of the greatest can be very difficult people. The saintly-looking and revered poet Robert Frost is revealed in biographies as a very difficult man. Frank Sinatra, a transcendent singer, had according to every account of his life, thuggish personal qualities.

Berry, with unusual candor, dispels any confusion that, as the creator of poems like “The Peace of Wild Things,” he is a superior person. He separates his art (“I honor the grace/that keeps this world”) from his personal qualities (“a man as crude as any, gross of speech, intolerant/stubborn, angry, full/of fits and furies”) for us.

Berry, acutely self-aware, views his gift for poetry (“That I/may have spoken well/at times”) as “A wonder is what it is.” In so doing, he draws us closer to him and to what he has to say.

Your comments are very welcome.

Thank you for analysis. I just find out Wendell Berry today and this post was helpful.

An excellent way to send us into a daunting new year.