The Underappreciated Edsel Ford

Edsel Ford's substantial contributions, in difficult circumstances, to his country, company, and city.

Henry Ford’s only son, Edsel, lived an event-filled life. He made exceptional contributions to the Ford Motor Company, to the Allies’ victory over the Axis Powers in World War II, and to the civic and cultural life of his native Detroit.

The urbane Edsel was very different from his father, who had only a grade school education. Edsel attended a Connecticut prep school, The Hotchkiss School, and college at what was then Detroit University School. Henry Ford’s single-minded drive to build cars and trucks as efficiently as possible, and to sell as many as possible, contrasted with Edsel’s more complex view of life, corporate responsibility, and his company’s future.

Edsel was an American business prince. He grew up trailing after his father as Henry built his first car, which he called a Quadricycle, in the garage behind his home on Bagley Avenue in Detroit and later as the rapidly-expanding company occupied a succession of ever-larger manufacturing plants.

Henry’s manufacturing dream came true at the massive River Rouge plant in Dearborn, Michigan which opened in 1920. At its peak, the Rouge employed over 100,000 people. The Rouge’s operations were vertically-integrated manufacturing on a massive scale. Henry had the Rouge River dredged so that freighters carrying iron ore from Minnesota could unload at the plant. Almost everything else required to build a car, from making steel to final assembly, was done at the Rouge.

Edsel as Ford’s President

Edsel was 25 when he became Ford’s President in 1919. His relationship with his father was tense and difficult. Henry often countermanded, frustrated, and humiliated Edsel. When Edsel directed that new coke ovens be installed at the Rouge, Henry had them torn out. When Edsel created space for an accounting department, Henry had it cleared out and fired the accountants. Edsel found them other jobs in the company. Edsel’s difficult relationship with his father is described in Ford—The Men and the Machine by Robert Lacey.

In Wheels for the World—Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress historian Douglas Brinkley wrote:

Dressing down Edsel became an almost daily routine for Henry who wanted his introverted son to be a tough-fisted power broker. To his credit, Edsel refused to be remodeled to meet his father’s notions of the perfect son. “The senior Ford never seemed to grasp the fact that his son’s differences in personality were a strength, not a failing,” historian Thomas E. Bonsall wrote. “Where Edsel was gentle, Henry saw weakness. Where Edsel was imaginative, Henry saw frivolity. Henry spent years trying to make Edsel into a carbon copy of himself instead of letting him be his own man.” (401)

Edsel’s interest in design was evident in the sleek cars he had built for his own use. More about his car collection can be seen

Edsel’s cars are kept at an expansive house on the shores of Lake St. Clair designed by architect Albert Kahn which is now a museum. More about the Ford House can be seen

Edsel saw a future for the company beyond car manufacturing. He led the company in the development of the Ford Tri-Motor airplane and championed the construction of an airport and the first airport hotel, the Dearborn Inn, which exists today. Edsel saw early that the engineering methods used in building cars could be applied to building airplanes, which had been mostly artisanal before World War II. Edsel’s dream was to sell inexpensive planes in Ford dealerships. Henry killed the idea.

Edsel also moved the company from Henry’s unyielding hatred of unions to meaningful negotiations with the United Autoworkers Union. Years of intimidation, union-busting and labor violence in Ford plants culminated in a brutal 1937 attack on UAW officials on a highway overpass outside the Rouge in what became known as the Battle of the Overpass.

The UAW organizers were attacked and beaten by men from the Ford Service Department, a private army of thugs and spies controlled by Henry Ford’s right-hand man, Harry Bennett.

The company’s resistance to organized labor eventually ended. Brinkley explains:

However, on June 20, 1941, the Ford Motor Company signed a landmark agreement with the UAW. Henry Ford’s last surprise was the contract itself, offering even more liberal terms than the union had requested. Once Henry Ford accepted the idea, he wanted it to be done right, with the result that Ford workers received a much better contract than their counterparts at GM or Chrysler. (432)

Historian Thomas E. Bonsall summed up Edsel’s contributions to the company in his book, Disaster in Dearborn—The Story of the Edsel:

It was Edsel who persuaded his father to buy the Lincoln Motor Company at a receiver’s sale in 1922. It was Edsel who finally persuaded his father to retire the antiquated Model T. It was Edsel who then directed the highly successful styling of the Model A, which, as much as anything, put that all-important model across to the public. It was Edsel who saved Lincoln in the depths of the depression by creating the upper medium-priced Lincoln-Zephyr. It was Edsel who saw the need for a mainstream medium-priced care to enable Ford Motor Company to compete head-to-head with General Motors and Chrysler, and created the Mercury. And, not least, it was Edsel who gave the company the three sons who would, after their father’s death, save it from their senile grandfather and his thuggish cronies. (38-39)

Edsel would never run the company without his father’s interference. After Edsel died at 49 in 1943, his father, then 80, reassumed control of the company which accelerated its descent into chaos. The erratic and failing Henry relied heavily on Bennett. As a result, the future of the company was in serious doubt. Bennett attempted to get Henry to sign a codicil to his will that would have given Bennett even more authority over the company.

Two years after Edsel’s death, the Ford family, led by Edsel’s son, Henry Ford II, asserted itself and fired Bennett and numerous other employees loyal to him.

My Connection to Harry Bennett, Edsel Ford’s Nemesis

The historical accounts are essentially unanimous that Harry Bennett was a bad man. His principal traits were a fierce loyalty to Henry Ford and a willingness to use violence against Ford’s enemies, real or imagined.

Bennett, a World War I Navy deep-sea diver and who boxed as “Sailor Reese,” started at the company at 24 in 1917, about the same time as Edsel. He catered to Henry Ford’s every whim. Henry thought Bennett was indispensable and Bennett was often Henry’s instrument in countermanding or frustrating Edsel’s plans for the company.

Bennett’s influence with Henry grew through the 1920’s and 1930’s. In The Fords—An American Epic, co-authors Peter Collier and David Horowitz describe Bennett’s role:

Entering the Ford saga relatively late, Bennett changed it from the spectacle of an increasingly bitter and fitful old man unwilling to relinquish power into a Byzantine court drama filled with treachery and intrigue, dire struggles for power and real physical danger. (152)

Through Henry Ford, Bennett acquired a large home on a bend in the Huron River, just east of Ann Arbor. The Castle, as it came to be known, reflected Bennett’s well-founded concern for his personal safety. Bennett built turrets with gun emplacements, rooms with secret compartments for weapons, and a hidden escape tunnel to the river.

Bennett, a smallish man, liked to show that he could control large animals, for example, horses, which he would bring into the house during parties. Bennett kept lions, which he would show off to guests, in concrete cages with steel bars in a building near the main house. Here are front and rear views of the Castle:

I grew up in Ann Arbor and was looking for work during summers and school vacations. In the spring of 1970, my career in the aftermarket sector of the automotive industry ended when was I was laid off from a Midas Muffler shop on Washtenaw Avenue. I needed work right away.

I approached Harold Stark, the then-owner of the Castle and surrounding property about a job. Mr. Stark controlled Electro Arc, a manufacturer of metal disintegrating machines, on the estate. The United States Navy was the principal customer for Electro Arc’s machines which could remove a broken bolt or machine screw without damaging the threading that held it. Thus, a repair job that would ordinarily require a ship to return to port could be done at sea.

Mr. Stark said, “I only have outside work.” So, that summer I did nothing but cut up downed trees around the Castle property with a chain saw.

In the woods with my chainsaw, I saw a deep partially excavated V-shaped trench that ran across the neck of the bend in the river. Bennett’s plan, which was never completed, was to divert the river to channels on both sides of his house to create a natural moat.

During a winter break, a co-worker, Jim Rutherford, and I broke up the very thick concrete floors of the lion cages adjacent to the Castle with an electric jackhammer. Mr. Stark wanted the cages remodeled into stables and the concrete was too hard (clay is the preferred material) for his horses’ hooves. We carried the broken concrete chunks out in drywall compound buckets, some of the hardest work I have ever done.

Edsel Ford and the Arming of America: The Willow Run Bomber Plant

Henry Ford was a vocal pacifist and isolationist. During World War I, he was a major organizer of the Peace Ship, an ocean liner that traveled to Europe to prompt a peace conference to end the war.

Despite Henry’s history, Edsel convinced him that the company should play a leading role in gearing up America’s manufacturing base for World War II. Along with veteran executive Charles (“Cast-iron Charlie”) Sorensen, Edsel acted as the intermediary between the company and the Roosevelt Administration as Ford pivoted from making cars and trucks to making armaments.

Edsel and Sorensen were the driving force in the construction of Ford’s massive Willow Run bomber plant where over 8,000 B-24 Liberator bombers were built.

A.J. Baime’s book, Arsenal of Democracy-FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War details the logistical and engineering challenges that Ford and Sorensen overcame as they fulfilled their commitment that Willow Run would build “a bomber an hour.”

Baime summarizes the Ford Motor Company’s astonishing war production this way:

Of the total 18,482 Liberators built during the war, 8,685 of them rolled out of Willow Run. A total of 80,774 workers (61 percent men, 39 percent women) staffed the bomber plant, with a peak employment of 42,331. The cost to make each Liberator dropped from $238,000 per ship at the beginning of production to $137,000 at the end. Under the guidance of Edsel Ford and Charlie Sorensen, Ford Motor Company also built 57,851 aviation engines at the Rouge, plus 277,896 Jeeps, 93,217 trucks, 26,954 tank engines, 2,718 tanks, 87,390 aircraft generators, 52,281 aircraft superchargers, 10,377 squad tents and 2,401 jet bomb engines (which powered the new JB-2 Loon, the American copy of Hitler’s VI and V2 flying bombs, the first-ever pilotless missiles.) (286)

According to Baime, the total value of Ford-produced war materiel, in 1945 dollars, was $4,996,314,000 or about $87 billion in today’s dollars.

Edsel Ford as Civic and Arts Leader: The Detroit Industry Frescoes

As a leading member of the Ford family, Edsel was invited to lead, or support, numerous Detroit civic institutions. He gave his time, and his wealth, generously to numerous local organizations. He was particularly devoted to the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) where he was a trustee. According to Brinkley, “during the Depression [Edsel] underwrote salaries and other major expenses to make sure the museum stayed open.” (402)

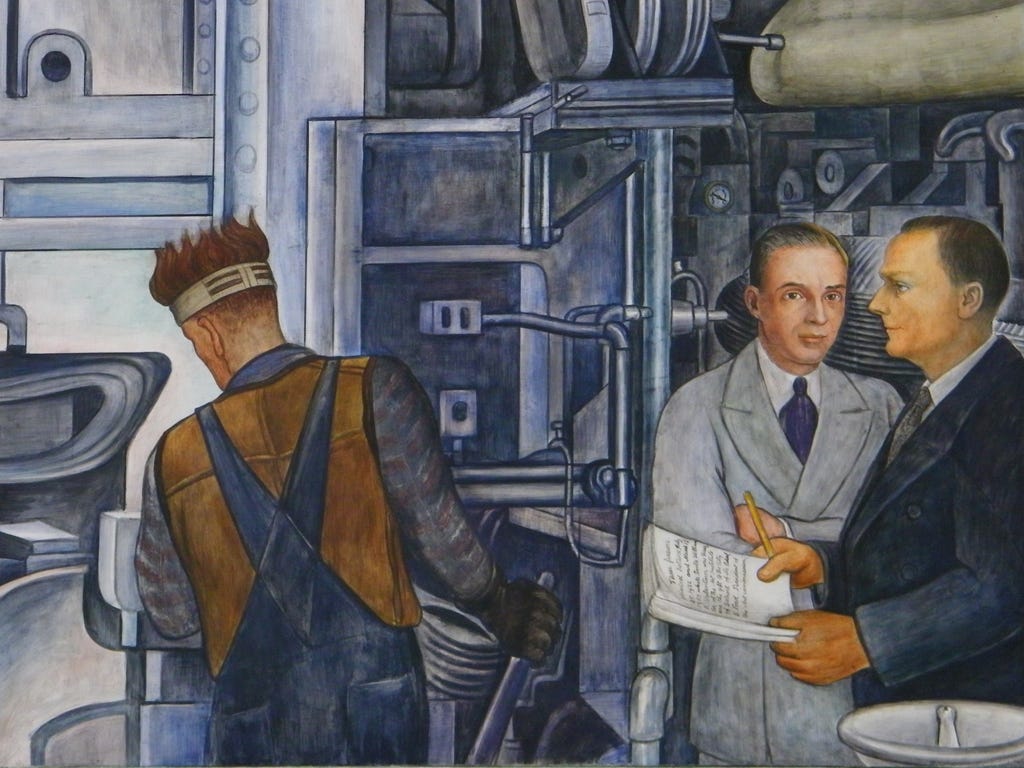

In 1931, Edsel commissioned the Mexican artist Diego Rivera to create a mural in honor of Detroit’s workers in the museum’s central court. Rivera’s 27 frescoes were painted on wet plaster as the artist stood on a scaffold, a technique dating to the Renaissance. It took Rivera eight months to complete the commission. More about the Detroit Industry Frescoes can be seen

Brinkley describes Rivera’s arrival in Detroit in 1932 to begin work at the museum and the limited, but thoughtful, guidance that Edsel gave Rivera:

After Rivera settled in, Edsel gave him a personal tour of the Rouge. “Ford set only one condition,” Rivera later wrote, “that in representing the industry of Detroit, I should not limit myself to steel and automobiles but take in chemicals and pharmaceuticals, which were also important in the economy of the city. He wanted to have a full tableau of the industrial life of Detroit.” (403)

That Rivera was a registered member of the Communist Party in Mexico apparently did not matter to Edsel. He hired Rivera for his art, not his politics.

Renaissance fresco painters often portrayed their patrons. Here is one of Rivera’s panels showing Edsel Ford and then-DIA Director William Valentiner:

A Tribute Car Gone Wrong

In 1957, the company, under the leadership of Henry Ford II, announced a medium-priced car honoring Edsel Ford for the 1958 model year. The Edsel was aimed at upwardly mobile young executives and professionals and was designed to fill in a gap in the company’s product line, allowing it to compete more effectively with General Motors and Chrysler.

Despite significant promotional fanfare, the Edsel failed in almost every way: styling, marketing, engineering, and quality control. A hypercritical press seized on the car’s flaws and a national recession contributed to weak sales. The Edsel was the wrong car at the wrong time

For a time, the description of something as “an Edsel” signified a disaster of some kind. By 1959 the company had essentially given up on the Edsel.

Bonsall writes:

Yet, of all the indignities Edsel endured, one of the cruelest must surely have been one that transpired after his death: the naming of the Edsel automobile. Thus, even though it came about more than a decade after his demise, the best-known fiasco—at least to the general public—in the automobile industry remains indelibly associated with Edsel Ford. (39)

What Edsel Ford Teaches Us

Edsel Ford is not overlooked (a section of Interstate 94 in Detroit is named the Edsel Ford Expressway and my high school competed against Dearborn Edsel Ford High School. ) More accurately, he is underappreciated.

Edsel assumed a critical role in a company dominated by its famed founder, his father, often referred to as the inventor of the modern age. Henry Ford was a great man in that he changed the way people lived. Edsel Ford was a good man who was on the right side of history in almost every sense. This is not a small achievement.

Edsel made contribution after contribution to the Ford Motor Company, despite his father’s cruel interference. Together with key Ford executives he mobilized the company as an engine of incredible productivity in World War II. And, Edsel gave his time generously to his city.

In our time, the dynamics of famous and powerful fathers and their sons (Fred Trump and Donald Trump, Robert F. Kennedy and Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Joe Biden and Hunter Biden) play out very differently. Edsel managed the blessings and burdens of being Henry Ford’s only son in admirable and constructive ways.

Perhaps the best way to understand Edsel is through Diego Rivera’s perceptive 1932 portrait. Rivera shows Edsel at work in a design studio. He is controlled and composed in an impeccably tailored double-breasted suit with a designer’s tools at the ready. The background is a large sketch of a sleek 1933 Ford coupe, one of the post Model-T cars that Edsel did so much to make a reality.

Special thanks to Rod Fonda for assistance with this post.

Thanks for reading About Alexandria!

Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

I loved this piece. I am definitely one of those people whose view of Edsel Ford was shaped entirely by the car. I knew his dad was a racist and anti-semite, but I had no idea how much of the company's success was due to his son. Plus, as a son of Pittsburgh, I love reading about the heyday of the industrial northeast. River Rouge was right up there with Bethlehem Steel Sparrows Point and Westinghouse East Pittsburgh (where my great-grandfather Frank Conrad was effectively the chief engineer of the electric company). They don't make them (or stuff) like they used to, at least not in the United States. Oh, and I'm a fan of the DIA. So thank you.

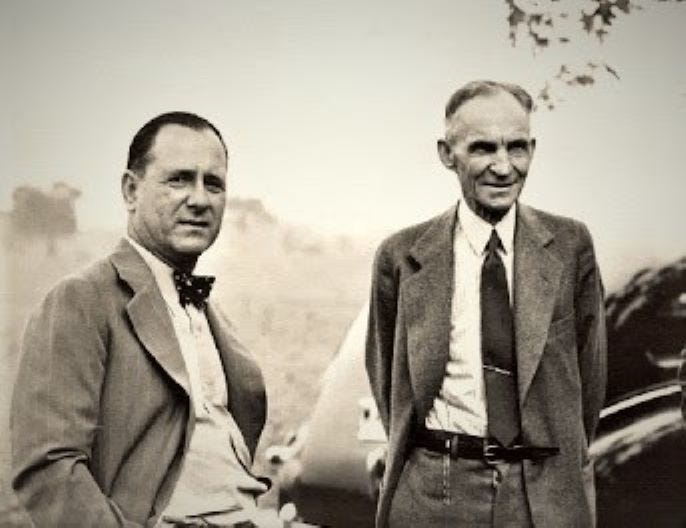

My family connection with Ford is depicted in a picture of Edsel, Henry and my grandfather Theron Ball Clement (available at https://www.dispatch.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2024/10/27/look-back-on-columbus-airports/75626716007/). Theron was the youngest of four very accomplished brothers. One of them, Martin, was a force within the Pennsylvania Railroad, eventually serving as its president from 1935-1948. So far as I can tell, Theron got all of his significant jobs from Uncle Winnie, as he was known in the family. In particular, the PRR partnered with Transcontinental Air Transport, the predecessor of TWA, to provide the first transcontinental air service. Passengers took the train from NYC to Pittsburgh because pilots didn't feel it was safe to fly over the mountains of PA. TAT flew Ford Trimotors on this route, and Martin gave Theron some role in the project. The picture was taken the day after the inaugural flight, at the dedication of the airport in Columbus, Ohio in 1929 (when my mother was not quite 2). My parents had the picture hanging in their house for years, but it disappeared when we closed the house a few years ago, so I was thrilled to find it online.

And Edsel's legacy still echos off the mountains on Mt. Desert Island, where we spend August. His house Skylands is one of great "cottages" remaining on the island. Martha Stewart bought it in the 1990s, which is a good thing — otherwise, Mitchell Rales probably would have bought it and torn it down, like he's done with not one but two historic homes there. Edsel's descendants either still live somewhere on MDI or come back to visit -- I've seen Benson Ford Jr.'s yacht bobbing around on Soames Sound.

Thanks again,

Jamie Conrad

Wrong caption on the photo with Harry Bennett--- that isn't Edsel Ford with him but Henry Ford.