The Reopening of the Freedom House Museum and "The Ledger and the Chain"

Guest contributor Len Rubenstein celebrates the reopening of the Freedom House Museum and reviews Jonathan Rothman's book, "The Ledger and the Chain."

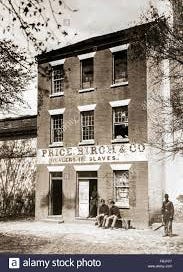

The newly re-opened and renovated Freedom House Museum on Duke Street is a gem, though its story is grim. It is on the site of the largest business engaged in buying and selling human beings in the United States from the late 1820’s through the 1830’s. The firm, Franklin and Armfield, was begun by Isaac Franklin and John Armfield, and later joined by a third man, Rice Ballard.

As you enter the museum, a large map shows the routes an estimated 10,000 people were trafficked from Alexandria to slave markets in the Deep South. Some were shipped to New Orleans; others were forced to walk more than 1,000 miles to Natchez, Mississippi. The latter is the first indication of what Jonathan Rothman, author of The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America (Basic Books, 2021), called the men’s “exuberant cruelty” that committed them to “hurt, degrade, and terrorize enslaved people.” The book and the museum together illuminate the firm’s origins, successes, and barbarity, and tell the stories of families broken up and subjected to unimaginable horror.

Start with that map. Rothman explains that a government geologist, George Featherstonehaugh, came upon a long line of about 300 people walking to Natchez. He was stunned by the “disgusting and hideous sight” of people chained together, each bearing 20 pounds of shackles.

The firm is the fulcrum around which Rothman explains the domestic slave trade that forced a million people from to the Deep South in the years before the Civil War, a consequence of the insatiable demand for slaves to grow cotton as tobacco farming faded in Virginia and Maryland.

Rothman shows how the three men revolutionized the internal slave trade by turning commerce in human beings into a diversified business. They purchased and chartered their own ships, which saved transport costs and provided an additional source of income from the space they sold to other traders on the ships. They created a network of agents who worked on commission to solicit the purchase of enslaved people to be sold in the Deep South. They regularly published newspaper ads offering to buy slaves in the District of Columbia, of which Alexandria was then a part. They operated their own slave pens behind their office and opened a sales office in Natchez.

And, perhaps most important of all, them firm revolutionized the financing of the slave trade by using credit to finance their operations and expand their business. They developed relationships with banks north and south so extensively that they contributed to the growth of the banking system in the United States.

By the early 1830’s the firm caused Alexandria to surpass Baltimore as the epicenter of trading in human beings bound for cotton plantations. The business made the partners fabulously rich as they prospered from the demand for enslaved workers and managed their way through declines in cotton prices, economic downturns, epidemics of cholera and measles, and the economic panic of 1832.

The trade was so enormous that southern governments began to fear the inundation of enslaved people. Mississippi’s legislature at one point outlawed the import of enslaved people into the state. New Orleans for a time prohibited sales in the city, and then regulated it, requiring certification that each person trafficked was over the age of 12, was of good moral character and had no record of running away. It also prohibited the importing of children under 10 unless accompanied by their mother.

Franklin, Armfield and Ballard were undeterred by the restrictions. Nor did they have any pangs of conscience. On the contrary, as Rothman shows, they and their associates regularly raped women in their pens, bragging to each other about it. While publicly claiming not to separate families, they built their business on doing so. Moreover, far from suffering consequences, or even opprobrium often associated with what many considered a distasteful business, they became respected and honored members of society.

That included Alexandria. The firm’s business and its owners were well accepted. While two of the partners never settled here, John Armfield did. His reputation was that of a noble and philanthropic member of the community. He built a 15-room mansion on Prince Street and joined St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where society and business leaders gathered on Sundays. Armfield’s wife was confirmed there. Efforts of abolitionists, members of Congress and societies seeking better conditions for enslaved people gained no traction in the city.

The firm disbanded as the price of cotton plummeted in 1837, but others took up their trade. The Duke Street site maintained its commerce in human beings until Union troops occupied Alexandria in 1861.

Franklin and Armfield, as well as Alexandria, are part of a larger story, as about a million people were trafficked to the Deep South in the decades before the Civil War. And, as Rothman writes, Franklin, Armfield and Ballard “profited by trafficking the enslaved to promote private gain and national growth” in a way that “could be leveraged for the benefit of nearly everyone except the slaves themselves.” In doing so, they were “vital gears in the machine of slavery, and they helped define the financial, political, legal, cultural and demographic contours of a growing nation.” The legacy has been continuing deprivation of wealth and ongoing discrimination against the descendants of slaves.

Our city has been a central part of that story, which was largely buried for generations, as a narrative dominated by Confederate myths about slavery and the Civil War prevailed. Although in recent years, the truth has begun to become accepted, the re-opening of Freedom House enables Alexandrians better to come to terms with the city’s role and its legacy, including those who struggled for both truth and racial justice. It is incumbent on us to recognize the ugly history and the legacy of injustice that has persisted for almost two centuries after the firm began its awful business and consider what reparations are necessary for justice. Freedom House and Rothman’s book are good places to start.