The History of the Johnson Memorial Pool

Pool memorialized tragically drowned Black children. From The Alexandria Times, December 22, 2022.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the 1952 dedication of Alexandria’s Johnson Memorial Pool. Named in honor of two Black children who drowned in the Potomac River, the pool was an important gathering place and recreation amenity for Black residents in Alexandria and Northern Virginia.

According to newspaper accounts, the pool was at the intersection of North Payne and First Streets, near Parker-Gray High School which opened in 1950 at 1201 Madison Street. The intersection where the pool was built no longer exists; North Payne Street now stops at Wythe Street.

Thus, the physical evidence of the Johnson Memorial Pool—the first swimming pool in Northern Virginia intended for use by African Americans—is now gone.

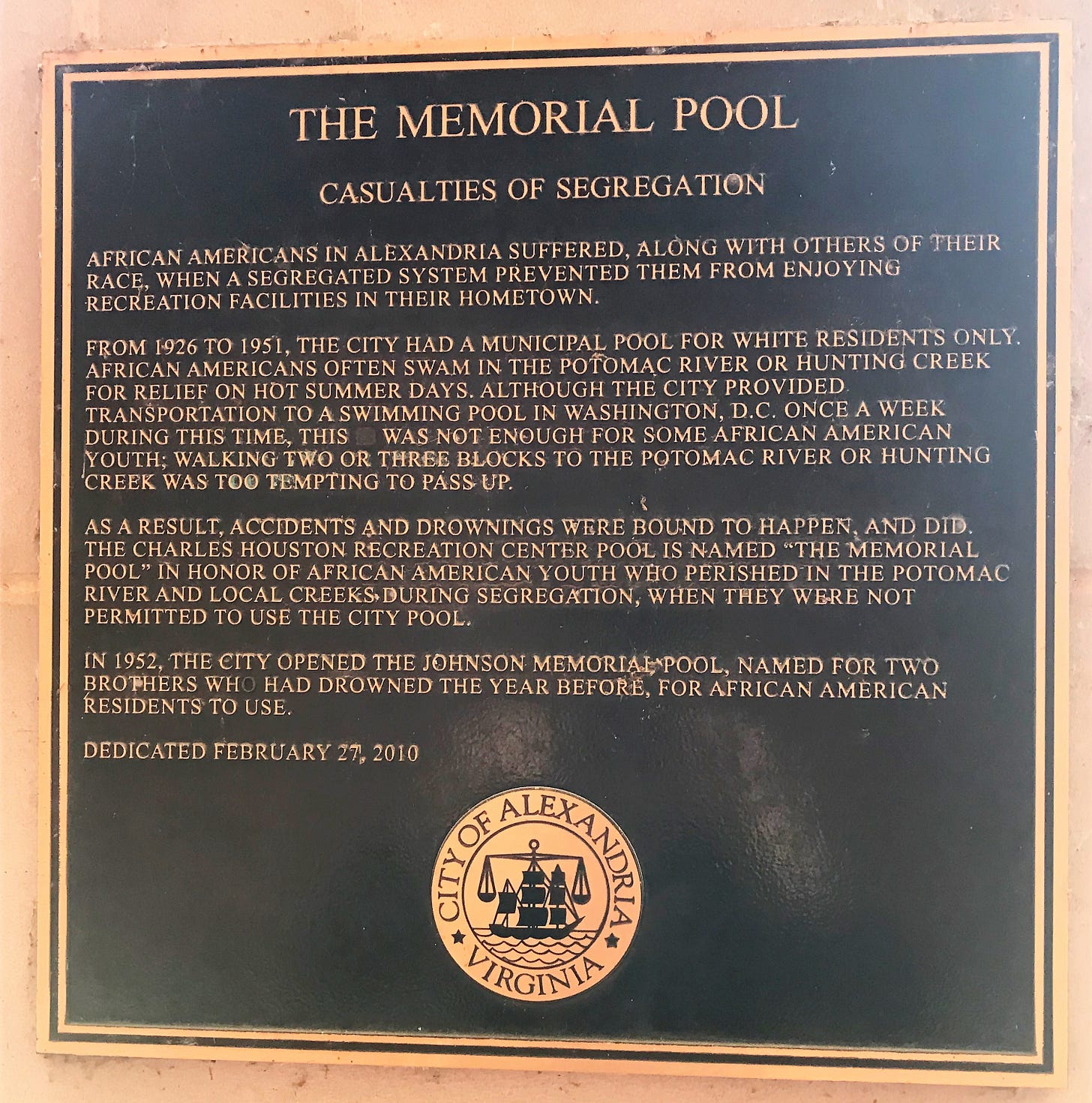

The Memorial Pool at today’s Charles Houston Recreation Center bears a 2010 plaque in memory of “…African American youth who perished in the Potomac and local creeks during segregation, when they were not permitted to use the city pool.” The Johnson Memorial Pool is referred to briefly in the last sentence of the plaque commemorating the dedication of the Memorial Pool.

Another plaque at the Charles Houston center contains the names of 9 swimmers, including the Johnson brothers, between the ages of 8 and 16 who drowned while swimming unsupervised. The plaque was sponsored by Rabbi Sylvan Kamens and Rabbi Jack Riemer.

However, the understanding of who the Johnson brothers were or why the pool was important to the African American community or how it came to be built in Alexandria seems to be fading with the passage of time.

A Devastating Family Tragedy

The Johnson Memorial Pool was named for brothers Lonnie and Leroy Johnson, ages 9 and 11, who drowned while swimming in the Potomac River on July 30, 1951. Contemporary accounts state that the boys attempted to construct a “boat” out of a cardboard box.

The carefully tended graves of Leroy and Lonnie Johnson can be seen today in the Oakland Baptist Church cemetery.

The Building Process

The assumption that the construction of the Johnson Memorial Pool was the sole and immediate result of an outpouring of empathy, or guilt, over the deaths of Lonnie and Leroy Johnson is not accurate. Alexandria’s civic leaders were well aware of the dangers of unsupervised swimming in the Potomac River and Hunting Creek. The efforts to build a pool for African Americans began years before the Johnson brothers died in the Potomac.

The Johnson Memorial Pool opened on May 31, 1952. The Alexandria Gazette reported on May 29, 1952, that the pool was not only dedicated to the memory of Lonnie and Leroy Johnson but was also the pool for Black Americans in Northern Virginia. The Gazette reported:

They died on the day before Alexandria officials won an appeal to the NPA [National Production Authority] to get vital building materials to construct the pool. The government approval concluded a four-year effort by civic and professional groups to get a municipal pool for Negroes. [The] [m]ajor argument was that Negro residents were swimming unsupervised in the Potomac River because there were no other facilities in the Virginia area.

The National Production Authority was established in 1950 as part of the Department of Commerce to develop and promote the production and supply of materials and facilities necessary for national defense. The NPA was charged with ensuring that building and other vital materials were available for the prosecution of the Korean War.

It is not clear how much of the four years it took to build the pool was attributable to NPA approval requirements, but such approvals must have been a factor in the length of time it took to construct the pool. According to a May 29, 1952 article in The Washington Post, the pool cost $100,000.

The Historic Importance of Swimming Pools

Jeff Wiltse, author of the book, Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, said in a 2008 National Public Radio interview that pools were a flashpoint for racial tensions because they were physically and visually intimate places. This led to a sense of fear, he said, of being exposed to dirt and disease of other swimmers. Wiltse said:

[I]t boils down to swimming pools being very intimate spaces, both physically intimate and also visually intimate. And so physically intimate, in the sense that you're sharing the same water. And there have always been fears, in terms of using swimming pools, about being exposed to the dirt and the disease of other swimmers.

And back during the 1920s and 1930s, and really continuing on even further up from there, there were racist assumptions that black Americans were dirtier than whites, that they were more likely to be infected by communicable diseases. And so, in part, the push for racial segregation and racial exclusion was for white swimmers to avoid being infected by the supposed "dirtiness" of black Americans.

But I argue that the primary and the most crucial cause for racial segregation was gender integration, that most whites did not want black men, in particular, to be able to have access to white women at such an intimate public space.

In the struggle for Civil Rights, the tensions over the desegregation of swimming pools in northern and southern communities are well-documented. For example, in 1964 a hotel manager in St. Augustine, Florida poured muriatic acid into a hotel pool to deter protestors seeking to integrate the pool.

Recreational swimming took on special importance as an expression of full citizenship. Alexandria resident Ericka Miller said, that for Black people, “Swimming was a political act.”

The decades-long national underinvestment in municipal swimming pools in Black neighborhoods contributed to a historically disproportionately high percentage of Black children who cannot swim. According to a 2017 study conducted by the University of Memphis and the USA Swimming Foundation, 64% of Black children did not know how to swim. The study found that they were six times more likely to die in swimming pool accidents than white children.

Wiltse notes that swimming and swimming pools were an essential public amenity in the early and middle parts of the 20th century:

The problem is that swimming pools today, municipal swimming pools today, are not nearly as high of a public priority as they were back in pretty much any time during the 20th century. I mean, during the early 20th century, especially during the 1920s, '30s and '40s, that pools were a very high public priority.

Lynnwood Campbell, a native Alexandrian, learned to swim at the Johnson Memorial Pool. He recalls that the pool was a very popular gathering place in the African American community with extended evening hours for adult swimming. Campbell remembers water shows and similar events and that African Americans came from all over Northern Virginia to use the pool.

Retired Alexandria Circuit Court Judge Nolan Dawkins said that he walked from his home to the pool through a marshy area in the north end of the city. Dawkins describes himself as a marginally capable swimmer. He said:

At that time, every person of color learned to swim at the Johnson pool; I had many friends at the pool. The water shows at the pool were outstanding, first class, events.

The Dedication of the Pool

White and Black Alexandrians turned out for the dedication of the Johnson Memorial Pool. Henry H. Fowler, a city resident and the NPA Administrator, was the principal speaker. Fowler was Chairman of the Recreation Committee of the city’s Community Welfare Council and among the group who appeared before the NPA before he became the authority’s Administrator to advocate for the allocation of critical materials to build the pool.

According to the May 31, 1952 edition of The Alexandria Gazette, Fowler expressed support for the pool’s dedication: :

It is fitting that we should dedicate this pool today. It is a symbol of our advance towards the equality of civic opportunity the Negroes of our nation are entitled to receive if we observe the Constitution and the Christian tradition which are our greatest American heritage—your heritage and mine.

Dr. Oswald Durant, Chairman of the Recreation Advisory Committee for the pool, served as master of ceremonies. According to the Gazette, he, “…hailed the completion of the pool as a thing the whole community had wanted—both Negro and white.”

Mrs. Morris Johnson, the mother of Lonnie and Leroy Johnson, also spoke at the dedication. Her remarks are compelling in their grace, dignity and generosity. The Gazette reported that she “thanked city officials and civic groups who worked for over four years to get a pool so Negro residents could swim in a safe and supervised place.” Referring to the deaths of her sons, Mrs. Johnson said:

If their sudden departure has hastened the day of its [the pool’s] operation, the bestowed shall not have been in vain, but their lives and service [have] become a benediction to man. My husband and I feel very humble in accepting this peculiar honor. We pray that the parents of Alexandria will profit by our loss, our sorrow and sacrifice, and that the gratitude of our youth to the recreation department will be expressed in terms, not dollars and cents, but in modest conduct and Christian character.

In saying that “the bestowed shall not have been in vain,” Mrs. Johnson may have been referring to a Bible verse:

1 Corinthians 15:10: But by the grace of God I am what I am: and his grace which was bestowed upon me was not in vain; but I laboured more abundantly than they all: yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me.

The Legacy of the Johnson Memorial Pool

How should the Johnson Memorial Pool be remembered? A positive perspective might be that Alexandria came together in the aftermath of a terrible tragedy to partially equalize the city’s public facilities and reduce the probability of unsupervised swimming deaths in nearby natural waterways. A different view is that the pool was one more government effort to maintain the pernicious system of segregation. These assessments are not mutually exclusive; each may be accurate.

Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for the Supreme Court majority in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), said that “separate but equal” had “no place in public education” because “segregated schools were inherently unequal.” The Supreme Court and the Congress ultimately applied the same principle to other public accommodations, including swimming pools, and it is undoubtedly true of the Johnson Memorial Pool.

With the hindsight afforded by the 70 years since its dedication, the best remembrance of the Johnson Memorial Pool may be a few moments of quiet appreciation for the Alexandrians who worked for years to build the pool in a thoroughly segregated state and city—and to appreciate the grace and dignity shown by Mr. and Mrs. Morris Johnson after the loss of their sons.

-aboutalexandria@gmail.com