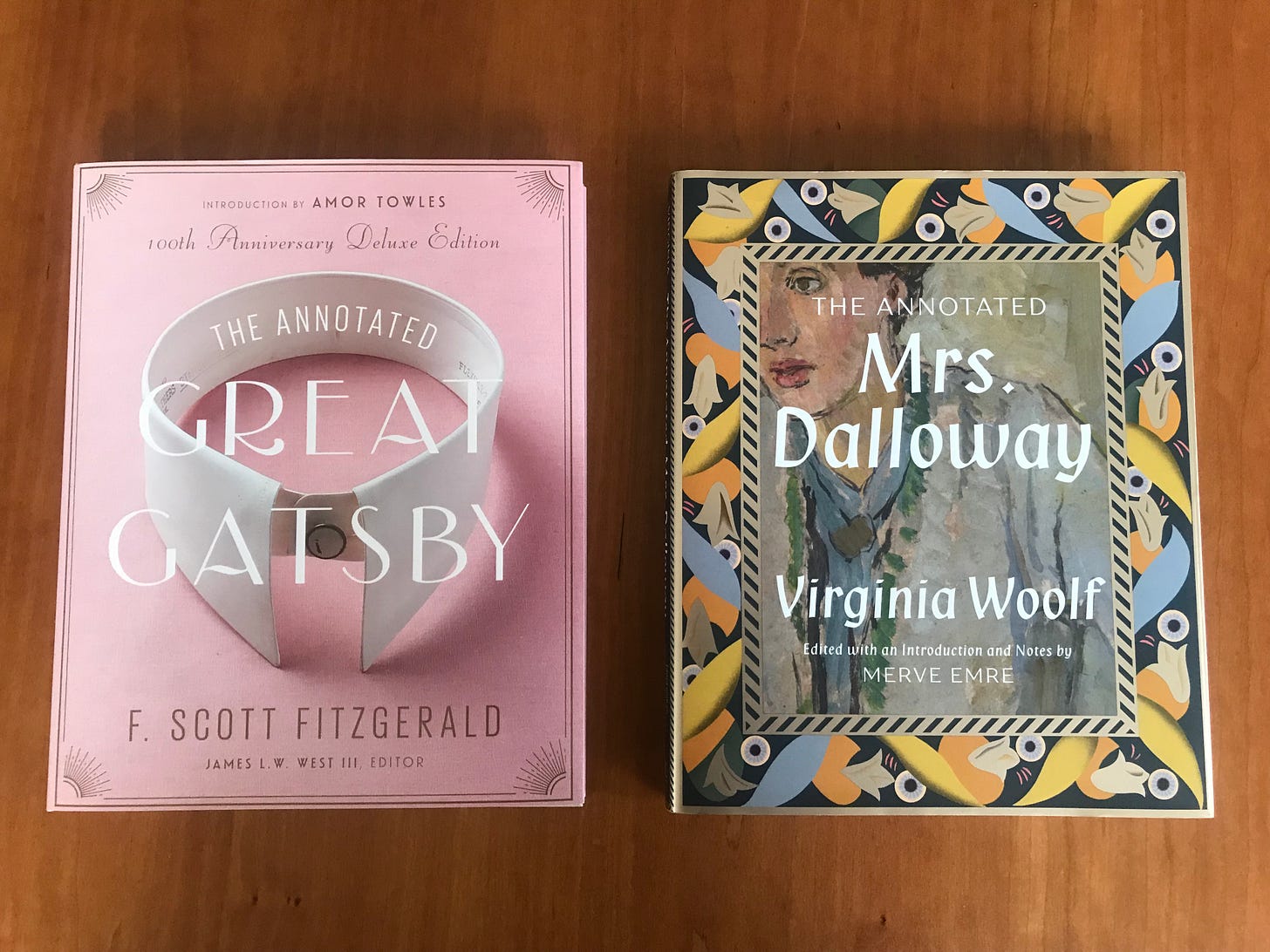

The Great Gatsby and Mrs. Dalloway at 100, Annotated

This year's centennial of two enduring novels and the rewards of their annotated editions.

English teachers, active or retired, are sometimes asked: “What books do you use (or did you use) in class?” and “Do you ever re-read a book”? The first question seems to be asked out of simple curiosity; the second seems to seek assurance that re-reading a book is an acceptable thing to do.

In 15 years of teaching high school English, I was fortunate to work in schools with well-stocked book rooms. I benefited from the shift from heavy and expensive textbook anthologies to single copies, usually in paperback. The curriculum included classics (Pride and Prejudice, The Scarlet Letter, The Awakening) and works by modern masters (Native Son, Beloved, Atonement) plays (Death of a Salesman, A Streetcar Named Desire, Fences) and poetry. Students were much more receptive to Shakespeare’s plays than I thought might be the case

As to re-reading books, “Why not?” If a book moves us on the first reading, it is probably worth rereading. Re-reading a work of fiction may reveal more than re-reading nonfiction, but there are people who do both.

Recently-published annotated editions of two novels that are mainstays of high school English, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, offer re-reading opportunities, and additional understanding and enjoyment.

The Public Domain: New Life for Old Favorites

On January 1, 2021, copyrighted works from 1925, notably Gatsby and Mrs. Dalloway, entered the United States public domain.

A copyright protects an author’s intellectual property rights in his or her work. A novel often takes on new life when its copyright protection ends. For example, a book inevitably becomes more widely available on services such as Google Books.

Generally, the copyright of a work created after January 1, 1978 lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years. For works published prior to 1978, the duration of a copyright varies depending on several factors. January 1 of each year is sometimes called Public Domain Day.

Duke University Law School’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain assessed 1925’s cultural achievements this way:

In 2021, there is a lot to celebrate. 1925 brought us some incredible culture. The Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. The New Yorker magazine was founded. The literature reflected both a booming economy, whose fruits were unevenly distributed, and the lingering upheaval and tragedy of World War I. The culture of the time reflected all of those contradictory tendencies. The BBC’s Culture website suggested that 1925 might be “the greatest year for books ever,” and with good reason. It is not simply the vast array of famous titles. The stylistic innovations produced by books such as Gatsby, or The Trial, or Mrs. Dalloway marked a change in both the tone and the substance of our literary culture, a broadening of the range of possibilities available to writers, while characters such as Jay Gatsby, Hemingway’s Nick Adams, and Clarissa Dalloway still resonate today.

Reading the annotated editions of The Great Gatsby and Mrs. Dalloway is like reading a book with a quiet, but very helpful, friend. What follows explores how annotated editions offer additional context, meaning, and enjoyment for books that may be very familiar.

The Great Gatsby Annotated

The Annotated Great Gatsby—100th Anniversary Deluxe Edition was published by the Library of America earlier this year. Edited by James L.W. West III, Professor of English Emeritus at Pennsylvania State University, the annotated edition adds new understanding even for readers already very familiar with Gatsby.

An annotated edition slows us down as readers, but in a good way. Annotations can add substantially to our understanding of the novel’s characters, time, and setting.

Gatsby is narrated by Nick Carraway, a Midwest native and Yale graduate. Nick is Jay Gatsby’s neighbor on Long Island and the cousin of Daisy Buchanan, for whom Gatsby yearns.

Early in the novel, Nick describes a female dancer at one of the massive shimmering parties at Gatsby’s mansion in a paragraph that West annotates twice:

Suddenly one of these gypsies, in trembling opal, seizes a cocktail out of the air, dumps it down for courage and, moving her hands like Frisco,3 dances out alone on the canvas platform. A momentary hush; the orchestra leader varies his rhythm for her, and there is a burst of chatter as the erroneous news goes around that she is Gilda Gray’s understudy from the Follies.4 The party has begun. (48)[1]

“Frisco” is probably a mystery to most readers, and there is only a hint about who Gilda Gray is (presumably, a performer at the Follies) and no information about who her understudy might have been.

Here are West’s annotations, which include illustrations not reproduced here:

3. In the dancing style of Joe Frisco (1899-1958), a comedian popular during the 1920’s. Frisco was famous for a soft-shoe shuffle, of his own invention called the “Frisco Dance.” Beginning in 1918, he was featured in The Midnight Frolic, a late-night floor show staged by the impresario Florenz Ziegfield (1867-1932) on the rooftop of the New Amsterdam Theatre, on West 42nd Street. He performed also in Vanities, a Broadway girly-leggy variety show produced by Earl Carroll (1893-1948.)

4. Gilda Gray (1901-1959), born Marianna Michalska, was a Polish American dancer and cabaret singer who popularized the “shimmy” in the 1920s. She performed the dance in the Ziegfield Follies, a Broadway revue with revealing costumery and elaborate sets. The shimmy was characterized by suggestive movements of the shoulders and hips (“I’m shaking my shimmy, that’s what I’m doing,” Gray explained).

Is knowing how Joe Frisco moved his hands, or that Gilda Gray’s understudy would know how to shimmy, essential to understanding and enjoying The Great Gatsby? Probably not, but the annotations confirm important things about Nick, and the book’s time and place, that are obscured for most of us due to the passage of time. Nick was not from New York, but he was no bumpkin. We learn that Nick is fully versed in New York’s entertainment culture. In short, Nick is hip and hipness, as exemplified in the Broadway’s entertainment culture, is important to the characters in the book.

Gatsby is a slow reveal: Nick gradually discovers the origins of Gatsby’s self-created life and invented back story, and his many lies. The annotated version describes how Gatsby, originally James Gatz, comes into focus for Nick, and explains seeming anomalies.

For example, Gatsby tells Nick that he is from the Middle West and this exchange ensues:

He looked at me sideways—and I knew why Jordan Baker believed he was lying. He hurried the phrase “educated at Oxford,” or swallowed it, or choked on it, as though it had bothered him before. And with this doubt, his whole statement fell to pieces, and I wondered if there wasn’t something a little sinister about him, after all.

“What part of the Middle West?” I inquired casually.

“San Francisco.”5

“I see.” (71)

Gatsby’s response, “San Francisco,” is odd. At first, it seems like a misprint or a production error. A common reaction to Gatsby’s response to Nick’s question might be, “Say what?”

Here is West’s annotation which adopts an explanation by a literary critic, the late Hugh Kenner:

5. Gatsby’s supposition that San Francisco is in the Middle West, Hugh Kenner writes, is a way of establishing “for the hasty reader of novels the fact that Gatsby is not quite what he seems to be.” A Homemade World, p.41.

Kenner’s premise, that many of us are “hasty readers” of novels, is undoubtedly true and it is another reason why re-reading books that move us is rewarding.

Nick’s measured response, “I see,” to Gatsby’s assertion that he hails from the Middle Western city of San Francisco is an effective two-word summary of a major through line of the novel. Much of Gatsby is about seeing: how Nick comes to see Gatsby, how Gatsby saw Daisy in the past and how he sees her in the novel’s present, and how Nick sees the forces that accelerated Gatsby’s rise and his sudden death.

The importance of sight, or seeing, is reinforced when Nick describes an image on a huge advertising billboard for an eye doctor in the valley of ashes which is halfway between Long Island, where Nick, Gatsby and Daisy live, and New York. In the valley of ashes, “The eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg are blue and gigantic—their retinas are one yard high, they look out of no face, but, instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose.” (31)

All this, and much more, is explained in West’s deftly annotated Gatsby.

Mrs. Dalloway Annotated

Virginia Woolf’s 1925 novel, Mrs. Dalloway, contrasts significantly with Gatsby. For example, in Gatsby, Nick tells us the story. We see and hear Jay Gatsby over time, but we are never in his head or aware of his thoughts. In contrast, Virginia Woolf puts us inside Clarissa Dalloway’s mind throughout Mrs. Dalloway. The novel takes place in a single day; the omniscient narrator relates Clarissa’s thoughts (and those of other characters) on a day in late June as she prepares to give a dinner party. Clarissa is the wife of a Conservative member of Parliament—a parallel story involves Septimus Warren Smith, a haunted World War I veteran.

The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, was published by W.W. Norton in 2021 and edited by Merve Emre, the Shapiro-Silverberg Professor of Creative Writing and Criticism at Wesleyan University. This thoroughly annotated version is a guide to the novel’s time and place and to the interior lives of its characters. The annotations also confirm Woolf’s extensive knowledge of the setting, London.

In this paragraph, Clarissa is on foot in London shopping for her party:

Her only gift was knowing people almost by instinct, she thought, walking on. If you put her in a room with some one, up went her back like a cat’s; or she purred. Devonshire House, 38 Bath House,39 the house with the china cockatoo,40 she had seen them all lit up once; and remembered Sylvia, Fred, Sally Seton—such hosts of people; and dancing all night; and the waggons [sic] plodding past to market; and driving home across the Park. She remembered once throwing a shilling into the Serpentine. 41 But every one remembered; what she loved was this, here, now, in front of her; the fat lady in the cab. Did it matter then, she asked herself, walking towards Bond Street,42 did it matter that she must inevitably cease completely; all this must go on without her; did she resent it, or did it not become consoling to believe that death ended absolutely? but that somehow in the streets of London, on the ebb and flow of things here, there, she survived, Peter survived, lived in each other, she being part, she was positive, of the trees at home; of the house there, ugly, rambling all to bits and pieces as it was; part of people she had never met; being laid out like a mist between the people she knew best, who lifted her on their branches as she had seen the trees lift the mist, but it spread ever so far, her life, herself.43 But what was she dreaming as she looked into Hatchards’44 shop window? What was she trying to recover? What image of white dawn in the country, as she read in the book spread open:

Fear no more the heat o’ the sun

Nor the furious winter’s rages.45 (17-18)

In one paragraph, Clarissa’s mind ricochets from her personal traits to the nature of memory and companionship, to Peter, a former lover, to mysteries of time, nature and death, to Shakespeare and elsewhere.

Emre’s eight explanatory notes locate us in Clarissa’s mind and world. Here is a summary of the annotations, numbered as in the annotated text:

(38) Devonshire House was the home of the imperialist William Cavendish, the 3rd Duke of Devonshire;

(39) Bath House was built by the Earl of Bath in the 18th century;

(40) the house with the china cockatoo was the home of Angela Georgina Burdett-Coutts, a baroness and philanthropist;

(41) the Serpentine is a forty-acre lake that separates Kensington Gardens from Hyde Park;

(42) Bond Street, a shopping mecca for the London’s upper classes, is the only street connecting Piccadilly to Oxford Street;

(43) here Clarissa contemplates the nature of individual existence;

(44) Hatchard’s Bookshop was London’s oldest bookstore; and,

(45) this is a passage from a dirge in Shakespeare’s play, Cymbeline, that encourages its listener to face death without fear.

Is it possible to read and enjoy Mrs. Dalloway without a complete understanding of the explanatory context provided in annotations such as the eight described above? Of course, but part of the joy of annotated versions is their continuing invitation to reread a passage or a chapter and to linger in a fuller understanding of the novel’s time, setting and ideas as revealed through the annotations.

A Few Final Thoughts

If you have read this far, thank you.

If you are interested in exploring annotated editions of other classic works, a good place to start is the Norton Annotated Series. You will not be disappointed.

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] All page references are to The Annotated Great Gatsby or The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway.

Special thanks to Charles Baxter and Patrick Welsh for assistance with this post.

Thanks for reading About Alexandria!

Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

Great column, all of it--but I can't get by San Francisco as a Midwestern city. Apparently, the lost concept of geography was lost earlier than I thought.