The Departmental Progressive Club at 95

Alexandria's home grown African-American community service and social organization celebrates its 95th year.

Racial Segregation Codified: Virginia Enacts “Racial Integrity” Laws

In 1926, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Public Assemblages Act which required the racial segregation of all public events and facilities. The statute mandated that if a white person entered, for example, a theater, African Americans were required to leave immediately.

The Public Assemblages Act was one of three “racial integrity” laws passed in Virginia between 1924 and 1930. The Racial Integrity Act of 1924 prohibited interracial marriage and defined as white a person “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian.” In 1930, a law was passed that defined as black a person with even a trace of African American ancestry.

A Matter of Necessity: The Founding of the Departmental Progressive Club

Another important event occurred in 1926: Alexandrians Jesse Carter, Lawrence Day, Clarence Greene, Raymond Green, Booker T. Harper, Jesse Pollard and Samuel Reynolds, all of whom worked in federal government departments, organized the Departmental Progressive Club (DPC) as a social and community service organization. The club continues to operate today from its Gibbon Street headquarters which dates from 1955.

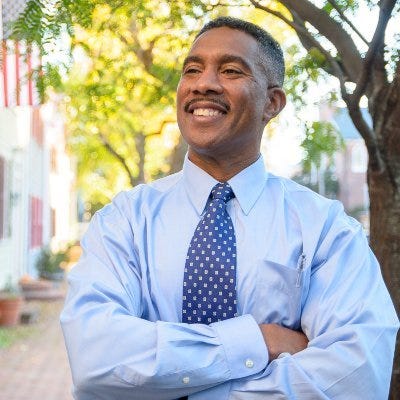

School Board member and former City Councilor Willie Bailey, former School Board Member Bill Campbell, Bill Chesley, the retired Deputy Director of the city’s Department of Recreation, Parks and Cultural Activities, and Merrick Malone, a real estate developer, attorney and former District of Columbia and Detroit official, have been DPC members and officers for decades.

Malone has lived in Alexandria since 2005. He said, “These seven men got together and really created the Departmental Progressive Club—you had mail carriers, elevator operators—to think of the strength and the vision of those seven founders to be able to come together and do that…the vision and the courage they had, tied together with comradeship.”

Malone said, “I like to say that we [the DPC] were created out of necessity. Back then, they would provide safe haven for kids having a place to study or to have a dance. They also began to fight for equality. During those times there was no alternative. It was one place that all African Americans could gather…because they couldn’t do it anywhere else.”

What the DPC Meant to Alexandria’s Youth

“Growing up, you heard of the club—they sponsored your teams, football, basketball…you just knew that they were out there supporting youth, somehow—the name was on the back of your jersey. Then, as you get older, you find out that your coaches were members of the Departmental Progressive Club,” Bailey said, “It was just a respected organization. You knew that this was one organization in the city that was doing something to help you as a black man growing up in Alexandria city.”

Bailey said, “I wanted to be a member to help give back… because I knew what the club did for me and folks like me growing up. Knowing that some of those folks were still members of the club, I owed it to them because of what they did for us.”

Chesley began working in Alexandria in 1980. He joined the DPC in 1988 at civic activist Melvin Miller’s suggestion. Miller was an active recruiter for the DPC. Chesley first became aware of the DPC in 1984 when he oversaw youth sports programs in the city and eventually served three years as the DPC’s President.

During the middle 1980’s Little League baseball teams were organized by residential boundaries which meant that teams with players from Alexandria Redevelopment Housing Authority properties were essentially all black. Chesley described how DPC members worked to defuse problematic interactions with parents over which teams their children would play on. Chesley said that the DPC’s leaders “definitely wanted to dispel” the idea that the DPC did not want white players on its team.

The DPC was represented at that time by Lawrence Day, Charles Nelson, Sr. and Lawrence Robinson. “I was really impressed that the club was really interested in not just putting money up to sponsor the team but had an active stake in coaching and making sure that the program went well,” Chesley said, “We pretty much navigated that—there were still some challenges there but they weren’t because of the club,” but rather because some white parents did not want their children to play on a DPC-sponsored team.

The DPC’s Alexandria Roots

Bailey said that young people in Alexandria may not know the DPC’s history or be familiar with the accomplishments of its members.

Malone said that because of affordability many DPC members who grew up in Alexandria now live in other jurisdictions. Bailey said, “That tells you a lot about how they feel about their city that they don’t even live in—they come back and are still members of the Departmental Progressive Club and give back to the community.”

“I marvel at the closeness of the African American community that grew up here—the nicknames, the stories,” Malone said, “The fabric created by those men—I feel like I know them.”

Malone has served on numerous corporate and nonprofit boards. “I can’t think of another organization that is more important to me than the Departmental Progressive Club. This is an organization that was founded out of necessity by African American men,” said Malone, “Think about how many organizations have come and gone in 90 years.”

An Accomplished Membership

Malone, Chesley and Bailey cited the leadership and accomplishments of DPC members Melvin Miller, Nelson Greene, brothers Lawrence and Ferdinand Day, Bill Euille, Earl Cook, Lawrence Robinson, Jackie Mason and others. Malone said, “A lot of leaders have come out of this club who were willing to put it on the line to press things like affordable housing.”

Bailey said, “If you look at any organization in the city that’s trying to do right by people overall, there are members of the club that are involved…we recruit each other to do that.” Malone said, “We sit on boards and commissions, that’s for sure.”

Campbell, the DPC’s current President, moved to Alexandria from the Seattle area in 2005. He said, “Every time I turned around, I kept running into people linked to the DPC,” including Jim Henson, Melvin Miller, Ferdinand Day, the Gray brothers, and Roy Priest, the Director of the Alexandria Redevelopment Housing Authority. As Campbell’s children progressed through ACPS they encountered DPC members in elementary, middle and high school.

Campbell said, “The DPC made me feel that Alexandria was a good place, although it still had some challenges.”

Campbell said that gentrification, the pandemic and an aging membership (some members have belonged for more than 45 years) reduced the DPC’s membership from a peak of about 125 to below 50. Campbell, the DPC’s current President, has made expanding the membership a priority.

The DPC’s Historic Headquarters

Malone said that Old Town has gentrified around the DPC’s Gibbon Street headquarters. Malone said that today, “You would be hard pressed to find a black family [that lives] around our club.”

Bailey described the relationship between the DPC and its Old Town neighbors as cordial. Bailey said, “The neighbors respect the club—when you’re there and you see them, they smile...And, we’re very respectful of our neighbors.”

Gentrification drove an increase in the assessed value of the building and in real estate taxes. The DPC’s headquarters now has an assessed value of $2.8 million. Malone sees the DPC’s headquarters as “our nemesis as well as our opportunity.”

Campbell and others are interested in exploring the possibilities of renovating the Gibbon Street building or a property trade similar to the one between the city and the Old Dominion Boat Club.

The DPC’s Next 95 Years

Malone, Bailey and Campbell said that there were occasions when each questioned whether his DPC involvement was worthwhile. Every time one of them considered resigning, he decided that the club’s history, particularly its tradition of community involvement, made it important to stay and work to sustain the club and rebuild its membership.

Campbell is particularly interested in involving the DPC’s historically important Ladies Auxiliary more directly and effectively. He said, “We haven’t done as good a job as we needed to with the Ladies Auxiliary.”

Chesley said that the Ladies Auxiliary was active in the past. His wife was a member of the Ladies Auxiliary, as was legendary activist Eula Miller, the wife of Melvin Miller. Chesley said, “I think it [the Ladies Auxiliary] has had a very respected and healthy existence.”

Campbell, Chesley, Malone and Bailey want to see the DPC engage more positively with Alexandria as an organization, not just through the reputations and accomplishments of its members. Campbell said, “We have as many prominent members as we’ve ever had.”

Malone is optimistic about the DPC’s future because of its younger members. Campbell agreed and said, “We need to do a better job of letting folks know that and also use that to continue rebuilding our membership.”

Malone believes there is a role for the DPC in Alexandria’s increasingly difficult affordable housing situation. He said, “When 90% of your [city] employees live outside of your city you need to be making affordable housing your number one priority.”

“If you look around, our [the DPC’s] base has shrunk. The city is becoming whiter, wealthier, and the question is to try to figure out how not to be ignored…I have always thought that, if allowed, this city could ignore people of color,” Malone said, “One of the things the Departmental Progressive Club is going to do is we are not going to allow people to ignore that we have underserved people of color in the city.”

Bailey added, “There are not a lot of organizations doing enough for people of color. Those folks who need help, who helps them?”

The DPC has a wealth of historic documents and has formed a Historical Documentation Committee to organize this material.

Campbell said, “For the next 95-100 years we still want to be in Alexandria, still doing things we’ve historically done, but in a modern way.”

Mark, thanks for this column. Impt for our community history.