The Best of What's Around: The Dave Brubeck Quartet, "Time Out," and "Take Five"

How musical experimentation met popular success for a 20th century jazz quartet.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet enjoyed an impressive run of popular success, particularly for a jazz ensemble, in the second half of the 20th century. Some jazz followers believe that commercial success devalues musical achievement—a wide audience is a sign of having “sold out.” Their idea is that for jazz to be worthy it must be obscure, even difficult, and appreciated or understood by a select few. The Dave Brubeck Quartet proved that this is not true.[1]

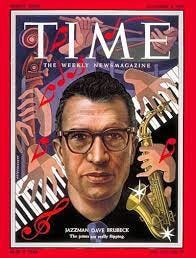

The video shows an odd sight: the Dave Brubeck Quartet in full flight looked like a group of accountants masquerading as jazz musicians. The quartet was widely popular on college campuses in the 1950’s. In 1954, Brubeck became only the second jazz musician (after Louis Armstrong) to appear on the cover of Time magazine.

Dave Brubeck—Piano

Brubeck was born in 1920 and grew up on his father’s 45,000-acre cattle ranch near Ione, California in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. His mother, Elizabeth, was a highly capable musician. She was tutored by composer Henry Cowell and at one point moved to London—the three children staying on the ranch with their father—to study the piano. She gave Brubeck piano lessons and taught him how to harmonize Bach chorales.

Brubeck was drafted into the Army in 1942 and sent to France in 1944. He was discharged in 1946 and went to Mills College in Oakland where he studied with French avant-garde composer Darius Milhaud. He formed a series of groups and in 1951 he added saxophonist Paul Desmond. The quartet remained together until 1967 when Brubeck disbanded it to focus on composing.

Here is how one critic assessed Brubeck’s popularity and his playing:

The fame and enormous record sales that Brubeck enjoyed were all the more remarkable given the uncompromising nature of his piano work. His approach to the keyboard was almost totally purged of the sentimental and romantic trappings or the oh-so-hip funkiness that characterized most crossover hits. His chord voicings were dense and often dissonant. His touch at the piano was heavy and ponderous—anything but the cocktail bar tinkling fancied by the general public. His music tended to be rhythmically complex, but seldom broached the finger-popping swing of [Oscar] Peterson or [Erroll] Garner. Only in his choice of repertoire, which was populist to an extreme with its mix of pop songs, show tunes, traditional music—indeed anything from “Camptown Races” to “The Trolley Song” might show up on a Brubeck album—did he make a deferential gesture to the tastes of a mass audience.[2]

Brubeck participated in the State Department’s Jazz Ambassadors program and toured Europe with his group in 1958. While in Turkey he heard street musicians playing in 9/8 time which prompted his curiosity about the possibilities of jazz in what were then unusual time signatures.

He was declared a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts and awarded the National Medal of the Arts. In 2009, he received a lifetime achievement award as part of the Kennedy Center Honors. Brubeck continued performing until his death in 2012.

Paul Desmond—Alto Saxophone

Paul Desmond (born Paul Emil Breitenfeld—“I picked the name Desmond out of the phone book,” he said) was born in San Francisco in 1924. His father played organ for silent movies, wrote band arrangements and accompanied vaudeville acts. He began playing the alto saxophone in 1943 when he was stationed in the Army. He said, “It was a great way to spend the war. We expected to get shipped out every month, but it never happened. Somewhere in Washington our file must still be on the floor under a desk somewhere.”

In 1987, the accomplished jazz pianist and long-time host of NPR’s Piano Jazz, Marian McPartland, published All in Good Time, a collection of her articles from Esquire and Down Beat magazines. Her portrait of Desmond is especially affectionate:

For Desmond has a mind that can only be called brilliant—incredibly quick, perceptive, sensitive. He is also remarkably articulate (his original goal in life was to be a writer, not a musician) with a skill at turning apt and hilarious phrases that leave his friends in hysterics. (p. 55)

Brubeck said that Desmond was “one of the few true individuals on his instrument” and one of very few saxophonists who did not imitate the colossally influential Charlie Parker.

McPartland said that Desmond “pursuing his own musical ideal, and his distinctive sound—light, liquid, at times mournful—will continue to be an important voice in jazz.” She quotes Desmond as follows:

I love the way Miles plays. I still think the hardest thing of all to do is to come up with things that are simple, melodic, and yet new. Until fairly recently, most of the landmarks in jazz history could be written out and played by practically anybody after they had been done. It just took a long time for them to be thought of. There’s a lot more going on now in terms of complexity, but it’s still a long time between steps.

And:

What would kill me the most on the jazz scene these days would be for everybody to go off in a corner and sound like himself. Let a hundred flowers bloom.

Diversitysville. There is enough conformity in the rest of this country without having it prevail in jazz, too.

The critics who saw Brubeck heavy handed on the piano were often entranced by Desmond’s lyricism on the alto saxophone.

Desmond was a member of the quartet from 1951 to 1967. For a comprehensive account of Desmond’s music and life see, Take Five—The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond (with a forward by Dave and Iola Brubeck) by Doug Ramsey, Parkside Publications, Inc, Seattle, Washington, 2005. Desmond died in 1977.

Joe Morello—Drums

Morello (in sunglasses in the video) was born in 1928 in Springfield, Massachusetts where his father was a painting contractor. His mother taught him the basics of the piano—his extremely poor vision limited his activities. He was precociously talented on the violin. At about 15, he took up the drums.

Morello honed his skills in various groups in Springfield, Boston and New York. In 1953 he joined McPartland’s trio where his reputation continued to grow. In 1956 he joined Brubeck’s group. Here is McPartland on Morello as a percussionist:

However, Joe is probably the one drummer who has made it possible for Dave to do things with the group that he would have had difficulty accomplishing otherwise. Joe’s technique, ideas, ability to play multiple rhythms and unusual time signatures, humor, and unflagging zest for playing is a combination of attributes few other drummers have. All these in addition to his ability to subjugate himself, when necessary, to Dave’s wishes yet still maintain his own personality.

Joe is fascinating to watch play—he may have several rhythms going at one time, tossing them to and fro with the studied casualness of a juggler. Yet through it all, the inexorable beat of the bass drum (not loud—felt more than heard) holds everything together. He moves gracefully, with a minimum of fuss, but with a sparkling, diamond-sharp attack, reminiscent of the late Sid Catlett.

In his time with the quartet Morello dominated jazz popularity polls, including the Down Beat magazine Reader’s Poll.

For rhythmically-challenged people, Morello’s ability to drum in several rhythms simultaneously seems like magic. Here is a 1995 clip of Morello appearing on Late Night with Conan O’Brien. If you have read this far, please take the time to compare the performance of the saxophonist in this video with Desmond. He is very capable, but his sound is very different than Desmond’s which is much lighter. The performance includes an extended “Take Five” drum solo in which Morello effortlessly manages complicated polyrhythms. At the end, Morello drops a drum stick twice. Somehow, it does not matter.

Morello died in 2011.

Eugene Wright—Bass

Eugene Wright was born in Chicago in 1923. He originally concentrated on the coronet before teaching himself the string bass. In 1958, at the Morello’s suggestion, he auditioned for and joined the Dave Brubeck Quartet.

Wright, a teacher by temperament who was later on a music conservatory faculty, was interested in Brubeck’s time signature experiments. He bonded immediately with Morello as Brubeck had with Desmond years earlier. Wright said:

Right away, Joe and I were as one. It was like Jo Jones and Walter Page with Count Basie. It was right from the beginning. When musicians used to ask me how I could play with that band, I told them they weren’t listening. I told them I was the bottom, the foundation; Joe was the master of time; Dave handled the polytonality and polyrhythms; we all freed Paul to be lyrical. Everybody was listening to everybody. It was beautiful. The people who couldn’t accept it were looking, not listening.[3]

An integrated jazz group in the 1950’s and 1960’s was the exception, not the norm. Brubeck, Desmond and Morello stood with Wright in difficult circumstances. In 1960, the quartet refused to play 23 dates at Southern colleges and universities because Brubeck would not replace Wright with a white bassist. In 1964, the quartet defied picketing and threats of violence by the Ku Klux Klan and performed before an integrated audience at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. Wright died in 2020.

Time Out and “Take Five”

The quartet’s most popular recording is the album Time Out, an experiment in jazz that departed from the traditional 4/4 time (four beats to a measure) signature which is often referred to as “common time.”

Most Western music is in 4/4 time and when Time Out was recorded virtually all of jazz was in 4/4 time. Time Out included works in 9/8 time (“Blue Rondo aﹶ la Turk”) and, most notably, “Take Five” in 5/4 time.

Brubeck was advised by executives at Columbia Records not to release the album. The album cover was unconventional: an abstract painting, rather than a picture of the quartet. Even riskier, the album contained exclusively original compositions and no standards. Even so, Time Out became the first jazz album to sell more than a million copies and the biggest hit ever by an instrumental jazz group.

“Take Five” was recorded on July 1, 1959 and seemed to embody mid-century American cool. Morello’s ability to keep time in various time signatures was essential to the experimental aspects of Time Out as was Desmond’s ability to write melodies that would work in 5/4 time.

Here is Brubeck on how “Take Five,” in 5/4 time, came to be:

The original beat—oom-chuckachucka-oomcha/oom-chuckachucka-oomcha—that’s Joe Morello’s beat. I knew I was going to do an album of all different time signatures, and I wanted Paul and Joe to do the five-four. See, they’d be warming up backstage before a concert, and Joe would say, “Come on, Des, let’s play in five!” which is very difficult to do when you’ve never played in five. You’re always stuck with that extra beat. But Paul could do it. So I said to Paul, “Joe’s got this five-four beat, can you put a melody over it? Write it for our next rehearsal.”

Well, “Take Five” was composed in my front room. Paul came to rehearsal with two themes. The first one was the bridge. And the other theme was the opening theme. Paul said, “I can’t write a tune in five. I’ve got these two themes but I can’t get them to go anyplace. I said, “Start with this theme and make this your bridge. And Paul caught on right away.”

I had to fight Paul to call this “Take Five.” He said, “Nobody knows what that means.” I said, “Everybody knows what that means except you, Paul!” Since its first release, I haven’t been able to play a concert anywhere in the world without someone screaming for “Take Five.” [4]

“Take Five” is instantly recognizable and has been covered by numerous artists. The composition swings, but with a complexity that makes it very listenable and it never seems to tire. The fifth beat in each measure braces and enhances Desmond’s soaring saxophone themes without infringing on them. Morello’s drum solo is interesting and efficient. Brubeck’s account of the origins of “Take Five” in many ways mirrors the Brubeck-Desmond connection at the heart of the quartet’s music. Here is how critic Whitney Balliett, a Desmond partisan, described the relationship:

In its final form, Brubeck, Desmond, Gene Wright on bass and Joe Morello on drums—the Dave Brubeck Quartet was one of the curiosities of jazz. Brubeck and Desmond were opposites. Desmond had a light, ethereal tone, and his solos were lyrical and singing and beautifully constructed. Brubeck, who had studied with Darius Milhaud and had dreamed of fusing jazz and classical music, was a heavy, erratic, passionate player who depended on repetition and difficult harmony for his effects. He could build a frightening rhythmic momentum with figures of almost no musical interest. Desmond was a blue summer day; Brubeck was thunder and lightning. Yet each man insisted that he would never have got anywhere without the other.[5]

The quartet relied on the classical music training of Brubeck, Desmond and Morello, the synergies and dynamism of the Brubeck-Desmond and Morello-Wright relationships, and the collective inclination to musical experimentation. The combination of an experimental approach with commercial success makes Time Out a jazz landmark.

The quartet’s popularity seemed to cause some jazz critics to take a negative view. And, Brubeck’s piano style turned off some critics while Desmond appears to have been a near universal critical favorite.

In his 1995 book, Cats of Any Color, former Down Beat magazine editor Gene Lees summarized what may be the best perspective on the Dave Brubeck Quartet: "The public was right; the critics were wrong."

The Dave Brubeck Quartet and Time Out: Let’s listen.

[1] In Visions of Jazz—The First Century, Oxford University Press, 1998, a comprehensive and informative history of jazz and jazz musicians, critic Gary Giddins intentionally omits Brubeck and calls him a “popularizer.” (See p.6)

[2] The History of Jazz by Ted Gioia, Oxford University Press, New York, 1997, p. 257

[3] Dave Brubeck, Time Signatures—A Career Retrospective (4 CD set), Sony Music Entertainment, Inc., 1992, p. 62.

[4] Ibid, p. 12.

[5] American Musicians II, Seventy-one Portraits in Jazz by Whitney Balliett, Oxford University Press, New York, 1996, pp 434-435.

Don’t know if you knew this story about Paul Desmond and Audrey Hepburn. From the New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/02/08/audrey-hepburns-favorite-song/amp

Good piece, Leonard Crook