The Best of What's Around: George Booth and the Art of Cartooning

How a master cartoonist and his frazzled cats and crazed dogs have kept us laughing for 50 years.

George Booth, 95, has contributed cartoons and covers to The New Yorker since 1969. The magazine has been a prominent venue for the art of cartooning since its founding by eccentric Editor Harold Ross and others in February 1925 [1]. Ross, who edited The New Yorker until his death in 1950, had a special affinity for cartoons.

Booth was born in Cainsville, Missouri in 1926 and raised on a farm. He drew his first cartoon, a race car stuck in the mud, at age 3. In 1944 he was drafted into the Marine Corps where he worked as a staff cartoonist on the Marines’ magazine, Leatherneck. To the amazement of his friends, he re-enlisted so that he could continue to work as a cartoonist on the magazine.

In 1952, after his discharge from the Marines, he married and moved to New York where he attended the School of Visual Arts. He worked in a series of magazine editorial and art director jobs and submitted cartoons to numerous publications.

Booth thought his big break had arrived when his cartoons were accepted by The Saturday Evening Post. Shortly after that good news in 1969, the Post ceased publication. However, his experience there resulted in a referral to The New Yorker’s Editor, William Shawn, who liked what he saw. The rest is cartoon history. Booth has published several collections of cartoons and won numerous cartooning awards.

Successful cartooning requires an unusual combination of skills and abilities; very few people possess all of them. Booth’s long career shows his extraordinary gifts in the art of cartooning.

Cartoonists must be able to draw, not necessarily with fidelity to reality, but in an interesting way that invites us into the scene. Cartoon admirers talk about the development of a cartoonist’s “line,” or distinctiveness of style. The line of a cartoonist that works over a long period of time evolves. For example, the early Doonesbury cartoons that Garry Trudeau did as an undergraduate at Yale are clearly by the same person who is drawing the strip today but the style is much different. Trudeau’s line has become clearer and more effective. The same is true of Booth.

Cartooning seems to be exempt from the “my kid could do that” school of criticism sometimes applied to modern art. Many people may draw “better” than Booth. However, Booth’s drawing style is impossible to imitate and essential to the content and effect of his cartoons. Booth’s line, and the kinetic/frenetic dogs, cats and people he draws, open the door to his unique world.

Cartoonists must come up with something to draw about. Cartooning is a visual art, but the content of a cartoon comes from human experience and eccentricity, not from the natural world of beautiful sunsets and waterfalls or other scenes that inspire painters and photographers. Great editorial cartoonists, for example Thomas Nast or The Washington Post’s Herblock or Tom Toles, were gifted visual distillers of political issues. Booth’s gift is that he can excavate humor, and cartooning material, from daily life and the imagined interactions of his everyman and everywoman characters and their crazed pets.

Here is a brief look at some Booth cartoons with a few suggestions about how they work. Trying to explain humor can be fatal to it; no effort will be made to answer the question, “Why is this funny?” More importantly, each of us should make a personal decision about humor. “Funny for you, not for me” is a fact of life.

A note to state and federal copyright law enforcement authorities: About Alexandria’s distinguished intellectual property counsel advises that the use of the following cartoons in this noncommercial context falls within the “commentary exception” to the general prohibitions of the copyright laws. So there.

The world of a Booth cartoon often centers on a domestic conversation fragment involving Mr. and Mrs. Everyman, a frazzled dog or cat, and a hanging bare lightbulb. Things in a Booth cartoon often seem to be on the verge of flying apart. In this one, the coffee maker on the counter on the left is about to explode. The briefcase covered with the hat and lying next to the umbrella, and the plate on the floor, are additional touches of uncertainty. The inverted caffeinated dog, of course, is the heart of the cartoon.

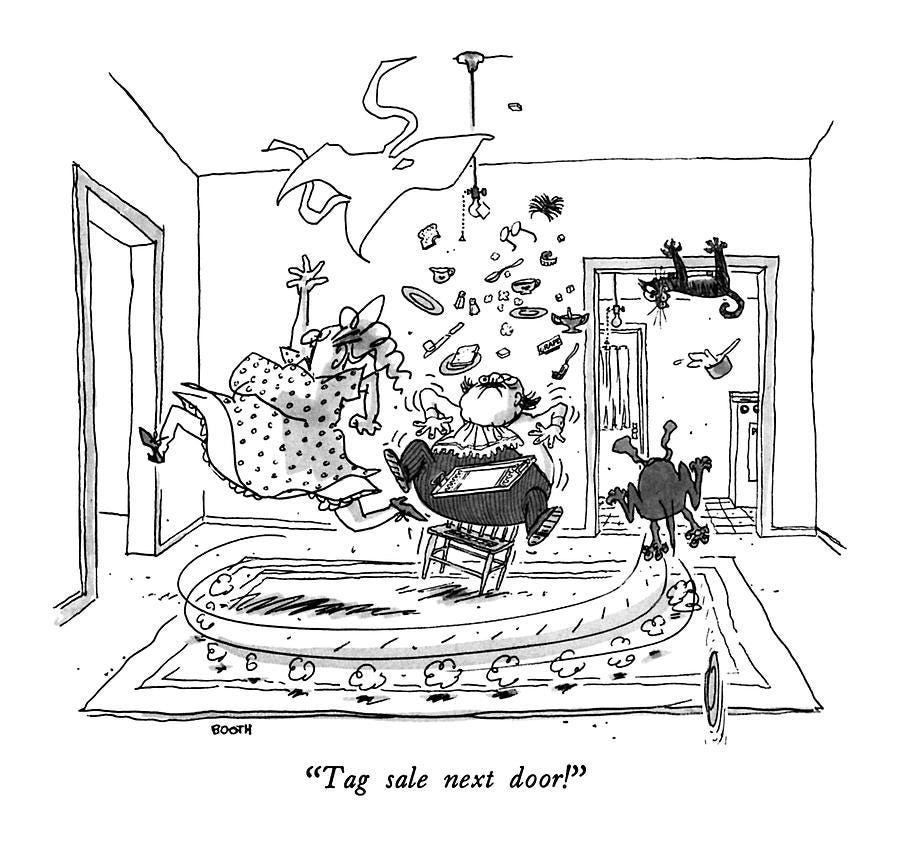

Booth often seems to put everyone and everything in motion to portray chaos. Here, as Mrs. Everywoman throws off her apron and sprints for the door the meal tray (and a toupee) explode, the dog whizzes through the dining room and into the kitchen, the cat is attached to the top of the door frame and the pot, for no apparent reason, flies off the stove. The plate rolling on its edge toward us in the right foreground completes the frantic scene.

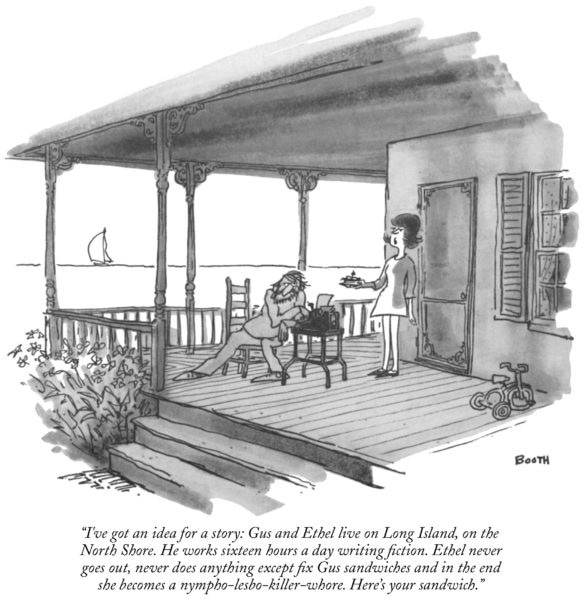

Comic strip cartoonists work in dialogue. Single panel cartoonists, such as Booth, must a be adept at writing captions or have someone write captions for them. Booth writes his own captions which are often long by most cartooning standards. This caption has Ethel interrupting Gus’ dedicated efforts to write fiction with a sandwich and a “story idea” that summarizes her view of their existence on Long Island.

In addition to domestic scenes, Booth has set numerous cartoons in automobile repair garages. This carton shows a garage with one of his hanging ceiling lights and a racyﹶ poster on the back wall. The dog is enormous—equal in size to the female mechanic who gives Mr. Ferguson the bad news. The effect is compounded by the enormous quantity of debris spilling out of the interior of the car and all over the floor—Mr. Ferguson’s car has serious problems and probably won’t be ready today.

Some Booth cartoons seem to be a coda, or add-on, to an undisclosed earlier conversation or series of events. We don’t know why Mrs. Everywoman thinks she has been rising from the ashes like a phoenix, but her convictions about continuing to do so are obviously very strong. She forcefully announces her view of things while Mr. Everyman has lowered his newspaper and a typical Booth dog faces us calmly. In contrast, the cat in the right foreground freaks out.

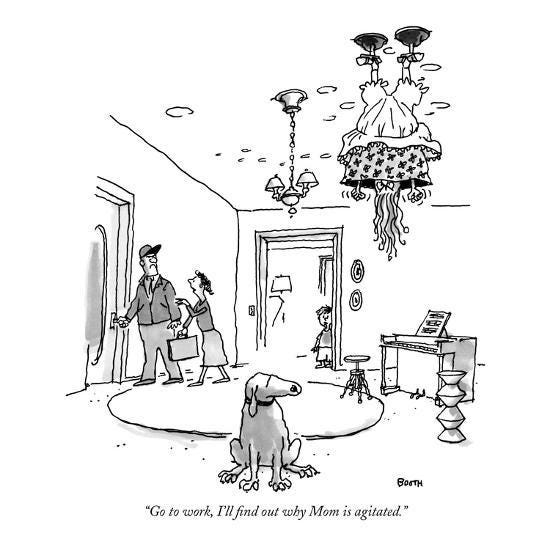

Booth’s cartoons often involve understatement and a cheerful suspension of the laws of physics. In this one, Mrs. Everywoman ushers her husband off to work while promising to find out why Mom is “agitated. This is an understatement considering Mom is walking around the ceiling with plungers on her shoes and is shaking. Mom on the ceiling recalls the cat in the second cartoon in this series. A little boy looks on from the background while one of Booth’s signature dogs is indifferent to Mom’s situation—it is not even worth turning around to look at.

In Drawing Life, a 2021 film directed by Nathan Fitch, Booth looks back on more than 50 years of cartooning. In the film, David Remnick, The New Yorker’s current Editor, and others describe Booth and his work, various unsolicited proposals of marriage to Booth, and other things. The film is a 23 minute week-brightener. You can see it:

Just for the fun of it: George Booth and his unique cartoons.

[1] The other magazine that paid attention to cartoons during its print heyday was Playboy. Hugh Hefner started his publishing career as a cartoonist and was always interested in cartoons. The New Yorker and Playboy always paid cartoonists more than other publications although, of course, the nature of the cartoons each magazine ran was very different. The New Yorker reportedly pays cartoonists in a range from $700 to $1,500 for each accepted cartoon. Cartoonists also make money by selling original art.

According to The New Yorker's website, George Booth has died at 96. I am sure that many join me in sympathy for his family and in gratitude for all the fun he gave us.

That's so great that you did an article about George Booth. My Mom always gets the New Yorker and I always look froward to seeing the comics. But I never realized how many of the comics I had enjoyed were created by Booth. I had no idea he'd worked for the New Yorker for so long! I also loved your descriptions of the cartoon.