The Best of What's Around: Carl Bernstein's Early Days in Journalism

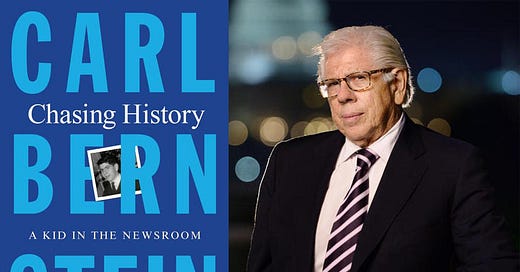

"Chasing History--A Kid in the Newsroom" tells how a marginal high school student began transforming into a legendary reporter.

Carl Bernstein’s career in journalism may be misunderstood, or at least incompletely understood. Bernstein will be remembered as the reporter for The Washington Post who, with Bob Woodward, broke the Watergate story. Bernstein, Woodward and the Post won numerous honors, including the Pulitzer Prize, for investigative reporting. He is now mostly known as a grey-haired CNN talking head. Bernstein seems to have permanent second billing—it is never the alphabetical “Bernstein and Woodward.”

Bernstein has written five books, two with Woodward. His post-Watergate career also seems overshadowed by the massively productive Woodward (author of 21 books) who regularly turns out fact-intensive insider accounts (for example, his Trump trilogy, Peril, Rage and Fear) and other writings.[1]

Bernstein is a Silver Spring native and the son of left-wing activist parents who were often under FBI surveillance. When he was a boy, his parents took him to a sit-in to desegregate the Tea Room at the Woodward & Lothrop department store.

His recent book, Chasing History—A Kid in the Newsroom, contains not a word about Watergate or his time at the Post or his misadventures in television news. Instead, the book describes his obsession with journalism from 1960 when, at 16, he talked his way into a copyboy position on The Washington Evening Star. Here is Bernstein falling in love with his life’s work as he sees the Star’s newsroom for the first time:

In my whole life I had never heard such glorious chaos or seen such purposeful commotion as I now beheld in that newsroom. By the time I had walked from one end to the other, I knew that I wanted to be a newspaperman.

In its heyday, the Star, then owned by the Kauffman and Noyes families, outclassed the Post and every other Washington newspaper with a staff of near-legendary reporters. The Star’s decline (it was an afternoon paper that could not overcome the increasing popularity of televised news) accelerated with the ascent of the Post. The Star ceased publishing in 1981.

Chasing History is a self-aware account of Woodard’s obsession with journalism and its people. Bernstein worked at the Star for six years starting in 1960 when it exemplified a newsroom of ringing phones, clattering typewriters, raffish hard-drinking reporters and demanding editors.[2]

Copyboys were messenger/assistants who did everything from delivering copy from reporters to editors to fetching coffee. Bernstein glories in the journalistic environment of this period, its traditions, personalities and even its practical jokes—in his earliest days Bernstein was directed by one of the senior reporters to report to the men’s room to wash out the carbon paper.

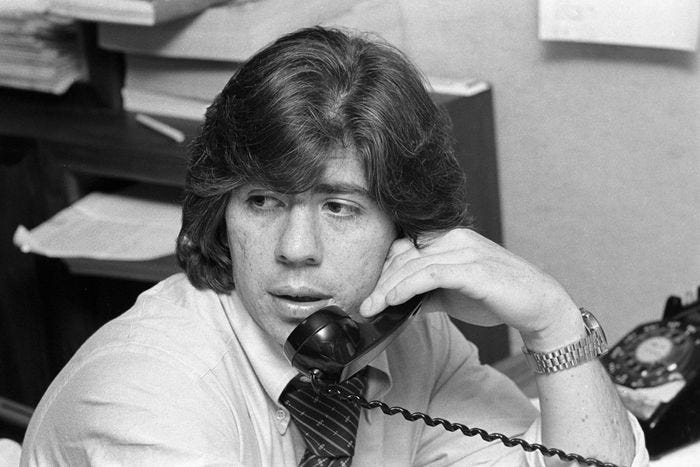

Besides natural curiosity about people, especially Washingtonians not involved in government, he had several talents that enhanced his work. He learned to read upside down and was a proficient (almost 90 words a minute) typist and had abundant energy. Bernstein says on several occasions that he “worked the phones” which appears to be no exaggeration. His prodigious capacity for work made him the go-to person when the Star’s editors were short-staffed.

Bernstein covered local government meetings, fires, murders and plane crashes. His account of showing his Star press pass to administrators at his high school so that he could join other reporters in covering a speech at the school by presidential candidate John F. Kennedy is a highlight.

Bernstein describes the tricks of the trade of police and fire reporters and how they managed to arrive at crime scenes and fires simultaneously with, or before, authorities. He quickly sees the difference between the working styles of firefighters (intense) and detectives (seemingly nonchalant) and learns how to get information from each.

Bernstein also describes the dubious activities of the Metropolitan Police Department’s Prostitution and Perversion squad led by a senior officer, Roy Blick. These officers operated at the edges of legitimate policing. Blick and his men engaged in entrapment schemes and figured prominently in the downfall of President Lyndon Johnson’s close aide, Walter Jenkins. Bernstein describes how the FBI sought to use the Star to publicize recordings of Dr. Martin Luther King in compromising situations, an invitation the senior executives at the Star declined. [3]

Chasing History shows Bernstein’s self-awareness and his candor. He is charmingly frank about his height (5’, 3” at 16), freckles, enthusiasm for journalism and distaste for most of what was offered at Montgomery Blair High School where he barely graduated. He has a comprehensive recall of every teacher, administrator and coach on his uncertain route to graduation. Bernstein combined an exceptional intelligence with an active distaste for any academic subject that did not interest him.

Good reporters cultivate sources; Bernstein cherished them. He developed a cataloging system to organize his notes about everyone from Eddie Bernstein (no relation) who led separate lives as a Washington panhandler and a real estate magnate in Florida to Annie, the owner of a downtown newsstand whom Bernstein memorialized in a front page Star obituary, to leading figures in the upper reaches of Washington society.

The Civil Rights movement had a special place in Bernstein’s heart and in his work as a reporter. He developed sources and friends among the Washington leaders of the Civil Rights movement, notably attorney Joseph Rauh, Stokeley Carmichael and the Reverend Walter Fauntroy. His account of the Star’s pre-Internet logistical arrangements for covering the March on Washington is a highlight.

Bernstein looks affectionately on institutions and places that served and connected Washington’s ordinary residents, not its rotating cast of government mandarins. Bernstein visits the Glen Echo amusement park, picks out his wardrobe at No-Label Louie’s and later at Lewis & Thos. Saltz, buys pastries at Reeves Bakery, and recalls the adult entertainment of 9th Street, N.W. and the Block in Baltimore. His extensive knowledge of Washington’s diverse neighborhoods (for example, Swampoodle) is remarkable.

Bernstein rises from copy boy to the dictation bank where he and others type up stories dictated by reporters in the field. Almost on a fluke, he is admitted to the University of Maryland. He continues to work full-time as a reporter and his college grades continue to suffer—he is dismissed from the university for excessive parking tickets, readmitted, dismissed, etc.

Ultimately, Bernstein’s academics impede his rise—admission to the Star’s training program for reporters required, in the minds of some, a college degree. A Star editor fatuously tells Bernstein, “Carl, experience is no substitute for the training program.” Bernstein concludes that his time at the Star is over. He gathers his impressive clips file and signs on as a reporter at a newspaper in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a prelude to joining the Post as a reporter in 1966.

Bernstein does remarkably little score-settling in Chasing History. His generous recollections of his friends and colleagues go back to high school. He describes his relationships with the Star’s colorful editors and reporters and provides a detailed Epilogue that describes the lives and careers of those he worked with at the Star, many of whom became his life-long friends.

Bernstein celebrates the talents of, among others at the Star, Lance Morrow, Haynes Johnson, David Broder and Mary McGrory whose sentences “danced across the page”. He looks back in gratitude, not resentment or envy. He seems to regret not one minute of the after-work drinking at Harrigan’s near the Star’s newsroom to “wait out rush hour” that was customary for Star reporters.

Bernstein does not say this, but here is the math: when the Watergate burglars were arrested on the night of June 17, 1972, Carl Bernstein, 28, had been a full-time, or nearly full-time, reporter with a major newspaper for 12 years. Bernstein and Woodward (for once) may have been young reporters, but Bernstein was anything but inexperienced.

1. The notion of Bernstein as Robin to Woodward’s Batman was confirmed in director Alan J. Pakula’s Academy Award-winning movie All the President’s Men (1976.) Dustin Hoffman’s portrayal of Bernstein’s relentless hustle (Hoffman leans forward for much of the movie) is particularly memorable in two scenes. In one, Bernstein surreptitiously rewrites Woodward’s lede (journalism-speak for the first 30-50 words of a news story.) Woodward (Robert Redford), ever upright and ethical, reads Bernstein’s revised version, objects to Bernstein’s meddling, and says, “Yours is better.” In the second scene, Bernstein shrugs off his reputation as a ladies’ man as he interviews a White House aide who resembles Cassidy Hutchinson in the rooftop bar of the Hotel Washington on 15th Street, NW.

2. Hollywood’s best portrayal of newspapering of this era was His Girl Friday (1940.) The cast, led by Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell, revels in breathless rapid-fire dialogue. The movie was directed by Howard Hawks. Grant plays conniving editor Walter Burns who seeks to win back, and re-employ, his ex-wife and ace reporter Hildy Johnson, played by Russell. Bernstein would have been a welcome addition to the cast.

3. For more on the activities of the Metropolitan Police Department and the Lavender Scare of the 1950’s when federal employees were fired for being gay, see the recently-published Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington by James Kirchick.