The Best of What's Around: A Day Trip to Antietam National Battlefield

Exploring the grounds of what may have been the real turning point of the Civil War with Alexandria's Mark Fitzsimmons.

Alexandria is close to numerous important Civil War battlefields because Union and Confederate forces fought between here and Richmond, and up and down the Shenandoah Valley, over the entire course of the conflict. So, with Civil War history available at reasonably close Manassas, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, etc., why drive the 90 plus minutes to visit Antietam National Battlefield near Sharpsburg, Maryland?

Why Antietam Matters

The battle of Antietam was fought on September 17, 1862. The battle’s strategic importance in the Civil War, its importance as a societal and political event, particularly with respect to the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation five days later, and the magnitude of the Union and Confederate sacrifice there, are compelling reasons to explore Antietam.

A rebuilt Visitor Center at Antietam is scheduled to open early next year. You can find out more about Antietam National Battlefield

It is also, paradoxically, a beautiful and natural place, that is not overly developed and commercialized, with great hiking trails.

A Local Expert Talks About Antietam

Alexandria’s Mark Fitzsimmons volunteers as a Battlefield Ambassador at Antietam.

Fitzsimmons explains why the future of the country was on the line at the battle there:

More Americans died there (including a large number born elsewhere) than in any other single day of conflict in US history (including D Day and 9/11). Many prominent historians (Bruce Catton and James MacPherson to name two of the better known) believe it was the real turning point of the war, not Gettysburg. The Confederacy had been on a winning run in the East since Robert E. Lee took over its main army. He invaded Maryland to pull Union forces out of their defenses at Washington and to produce a knockout victory on Union soil. Northern morale in the Army and across the population was very low, elections were forthcoming, England and France were considering intervening to push a resolution that included recognition, and there was a chance that Rebel troops in Maryland could push that state into the Confederacy. Lee believed beating the Yankees north of their border could lead to a negotiated settlement that recognized Southern independence.

An astonishing 23,000 men were killed, wounded or missing, including 6 generals, 3 on each side, killed in the single day of fighting. They are memorialized at an Annual Memorial Illumination. This year’s ceremony takes place on December 3.

More information about the Annual Memorial Illumination is available

Fitzsimmons sums up the importance of the battle this way:

The Union stopped Lee at Antietam. While it was not the complete victory that Lincoln hoped for (they did come close, several times over the course of the battle) the Confederates did retreat back into Virginia. The Southern momentum of the first half of the year was gone. Lincoln’s Republican party prevailed in the midterm elections and maintained a majority in Congress that supported his policies. The Europeans held back. And, of arguably more significance, the victory gave Lincoln the political capital he needed to announce the Emancipation Proclamation. That ended any chance that remained for some kind of negotiated settlement, and started the road to the end of slavery. African Americans were now also welcomed into the Union Army, and approximately 180,000 of them eventually served, close to 10% of the total Federal forces.

The Order of Battle

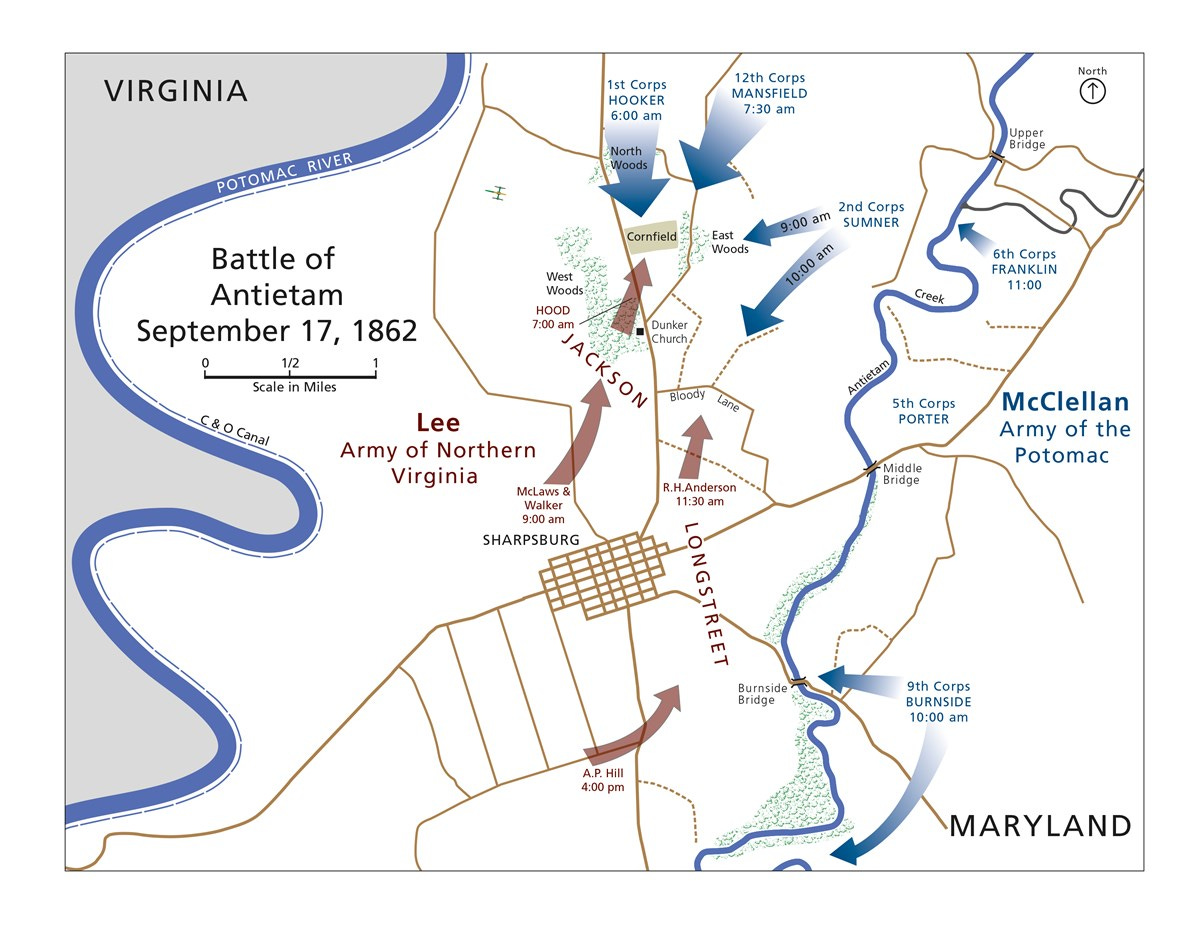

Here is the National Park Service’s map showing the alignment of forces at the battle:

The battle involved massive troop movements over large land areas. The Union commander, General George McClellan, did not fully coordinate the movements of his troops to take advantage of his 2 to 1 manpower advantage. Of the approximately130,000 men involved in the battle, about 87,000 were on the Union side while the Confederates fielded about 40,000 men.

The Union Army attacked all along the 4-mile front in a piecemeal, staggered fashion. This allowed the Confederates to shift men around to counter the Union assaults. McClellan showed similar caution after the battle when he failed to renew the attack with the relatively fresh troops he had, or pursue Robert E. Lee’s retreating Army of Northern Virginia with vigor. A short time later, and after the election, Lincoln replaced him, and eventually a year and a half later named Ulysses S. Grant to the command of all Union forces. Most historians credit Grant’s leadership with the eventual victory.

The Men Who Fought the Battle

Fitzsimmons explains that the history of the battle and the history of the men who fought the battle are inseparable. Antietam highlights one of the many great tragedies of the war, its “brother against brother” nature. There were Marylanders and Virginians in the ranks of both armies, and they faced each other directly at the Sunken Road. Many of the more senior officers on both sides knew each other, and many had been friends before the war.

The Union was able to favorably maneuver and move more quickly, and bring on the fight on its terms at Antietam, because it had found a set of lost orders from Lee directing his Army’s movements and scattering it all over Maryland days before. There was concern that the plans might be a ruse, but a Union officer recognized the handwriting and signature of the Confederate adjutant who drafted the order for Lee because they had worked together in Michigan before the war.

The first attack at Burnside Bridge on the southern end of the field was led by the 11th Connecticut, under Col. Thomas Kingsbury. The attack was repulsed by Georgians under the command of General David Jones. The two were brothers-in- law. Kingsbury was killed in the assault; Jones did not survive the war.

On the northern end of the battlefield, the Union commander on the ground and in immediate charge was Edwin Sumner. He was from Massachusetts and had two sons serving with him. But, his new son-in-law was a Virginian and on Robert E. Lee’s staff.

Fitzsimmons said:

Of course, my favorite character is Union General Israel Richardson. His nom de guerre was Fighting Dick. He was born in Vermont, migrated to Michigan, and had been a soldier but was a farmer when the war broke out. He was arguably the most pugnacious general on the Union side. He was looking for re-enforcements for a follow-up attack after his troops had driven the Rebels from the Sunken Road, which had opened up a huge hole in the center of the Confederate line, when he was mortally wounded. If he had been spared that, and remained to push the issue, the course of the battle might have been very different.

What to Do After Visiting the Antietam National Battlefield

Antietam Creek Vineyards is within walking distance of several battlefield monuments and is one of several wineries and breweries near the battlefield. More information is available

Shepherdstown, West Virginia is across the Potomac River, about 5 miles away from the battlefield on the road that the Confederates used to retreat. This scenic town is full of shops and restaurants. You can find out more