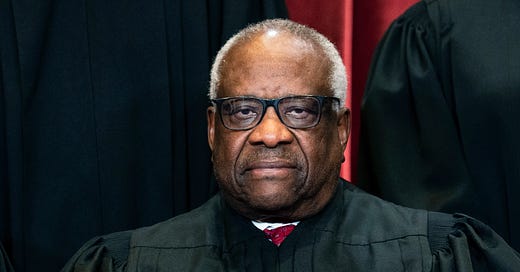

Say it ain't so, Justice Thomas

Thinking about judges and the appearances created by gifts to judges.

The undisclosed acceptance by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of lavish vacation travel from Texas billionaire Harlan Crow was followed by accounts of Georgia real estate transactions that resulted in Crow owning and improving the house occupied by Thomas’ mother. These events have sparked discussion about ethics and justices of the Supreme Court. The debate became more intense with the disclosure of Crow’s payment in 2009, also unreported by Thomas, of private boarding high school tuition for Thomas’ grandnephew.

Pro Publica’s reporting on Thomas’ acceptance of the gift of Crow’s tuition payments was detailed and measured in tone. The original article can be seen

Some appreciations of judges follow with a brief commentary on the Thomas-Crow financial transactions.

Why Judges Matter

I acquired a special respect for judges and their role in the legal system at Columbia Law School where I had classes with teachers that went on to distinguished judicial careers (Associate Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg) and with faculty members who were sitting judges (United States District Judge Jack B. Weinstein.) Some of the most talented members of my class (including federal judges Gerard Lynch and Denise Cote) had long careers on the bench.

Professor Ginsburg’s seminar on Conflicts of Laws was a remarkable experience. Conflicts of Laws, an arcane area of the law, focuses on how courts resolve cases that could heard in different jurisdictions. She taught the course, and other classes, while bringing and arguing a series of landmark Supreme Court cases that broke down gender discrimination in the law. For example, Professor Ginsburg brought, and argued in the Supreme Court, Weidenfeld vs. Weinberger which held that federal laws precluding widowers from collecting Social Security death benefits violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Professor Ginsburg, then in her pre-meme era, combined incisive thinking with astonishing clarity of expression.

Judge Weinstein, who died in 2021 at 99, was another special jurist. Here is how he was remembered by US Courts:

By any measure, Weinstein was a giant in the legal profession. A member of Thurgood Marshall’s legal team that prepared the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, he was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the Eastern District of New York in 1967. In 53 years, until his retirement in 2020, he reinvented how courts handle mass tort litigation, greatly upgraded the role of U.S. magistrate judges, and conducted himself in an egalitarian manner, wearing business suits instead of a robe in the courtroom and often sitting at a table with defendants as he sentenced them.

A complete account of Judge Weinstein’s extraordinary career can be seen

Judge Weinstein was the author of Weinstein’s Evidence, the definitive treatise on evidence in the federal courts. The law of evidence can be complicated. Judge Weinstein had such an outstanding reputation as a teacher that it was difficult to get into his evidence classes at Columbia (I was glad I did) which began at 7:30 am before he put in a full day on the bench at the federal courthouse in Brooklyn.

Judge Weinstein required students to visit his courtroom. I took the subway to the courthouse in Brooklyn where I watched him preside over a complex criminal case involving numerous racketeering and conspiracy counts alleged against leading figures in the New York mob. Sharkskin suits were prominent on lawyers and clients. Judge Weinstein handled every objection and motion with consummate ease.

When I graduated from Columbia, I was interested in trial practice so I took a job with a prominent litigation firm in Atlanta. I worked for John Marshall, one of the most accomplished trial lawyers in the country. John, who could have become a judge at numerous points in his career, showed a special respect for the judiciary. He described judges as the “flag officers” of the legal profession. One of John’s compliments for especially able jurists was that a judge “wore the robes lightly,” meaning that he or she discharged the duties of the judiciary with grace and dignity and without excessive self-regard.

Judges in Alexandria

Alexandria’s Carlyle neighborhood contains the Albert V. Bryan Courthouse, the federal courthouse for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Albert V. Bryan, Sr. was a federal judge for 37 years, retiring as a judge on the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. He was appointed to the District Court in 1947 by President Truman and to the Fourth Circuit in 1961 by President Kennedy. In 1958, Judge Bryan ordered that four African-American students be admitted to Arlington’s then all-White Stratford High School. His 1984 obituary in The Washington Post described him this way:

In 37 years on the federal bench, Judge Bryan developed a reputation for fairness, firmness and thoroughness--a courtly, conservative Virginia gentleman whose personal style was low-key, modest and polite, often with a measure of dry wit. Chief Judge Harrison L. Winter of the 4th Circuit appeals court recalled that a Baltimore lawyer who appeared often before Judge Bryan once said he was "old Virginia at its very best."

Albert V. Bryan, Jr., his son, was also a federal judge. He was nominated by President Richard Nixon in 1971 and served until 1991 when he took senior status. Judge Bryan helped make the Eastern District of Virginia the most efficient federal court in the nation—it was and is rare for a case to take more than 6 months from the date of filing to the trial date. I learned that Judge Bryan was extremely well prepared when he heard pre-trial motions.

Here is how one of his former clerks, Gregg Murphy, remembered him after his death in 2019:

Those of us who clerked for him were privileged to see him behind closed doors in chambers as he mulled over his decisions. He was resolute about making sure the judicial system treated everyone fairly but held the privileged accountable when they violated the trust bestowed upon them in society. Yet he was understanding and sensitive to those less fortunate due to the circumstances that burdened them in life.

Alexandria’s current and retired Circuit Court judges are prominent in the city. Each is meticulous in his or her awareness of the responsibilities of the judiciary. It seems inconceivable that any of them would compromise their reputations, or the judiciary, by accepting gifts that create an appearance of being beholden to the donor.

Thus, experiences in law school, law practice and after made it almost impossible for me, even today, to address a judge as anything but “Judge,” even in the most casual social settings.

Harlan Crow’s Unreported Tuition Payments for Thomas’ Grandnephew

It is probably not possible to know what was in Thomas’ mind when he accepted, and did not disclose, the luxury travel provided by Crow, or when he and Crow arranged Georgia real estate transactions to benefit Thomas and his mother. The tuition payments Crow made for Thomas’ grandnephew, however, are in a different category from the other gifts because there is evidence that Thomas knew that Crow’s 2009 tuition payments should have been reported.

In 2002 Thomas reported on the required disclosure form, under “Gifts,” a $5,000 “Education Gift to Mark Martin” from Earl and Louise Dixon. Martin is the grandnephew for whom Thomas had custody. According to Pro Publica, Dixon was the owner of a Florida pest control company.

How could Thomas report a $5,000 tuition gift in 2002 but fail to report much larger gifts—the tuition at Hidden Lake Academy in Georgia and Randolph-Macon Academy in Virginia exceeded $6,000 per month—when his grandnephew was in high school a few years later?[1] What changed in the years between the tuition gift from the Dixons and the gifts from Crow?

There seem to be no exculpatory answers to this question, nor any that would show Thomas in a positive light. Indeed, the facts invite negative conjecture. For example, were the 2009 high school tuition gifts not reported because (a) Thomas was sloppy, (b) Thomas did not care about the reporting obligations, (c) because of their source (Crow) or (d) because of the size of the gifts, or some combination of these? It seems inevitable that all of Thomas’ future ethics-related disclosures will be examined carefully by the media.

The respect I acquired for judges and the reports of the various undisclosed gifts and benefits Thomas accepted from Crow, particularly the tuition payments, have been difficult to reconcile.

Some suggest that because there has been no evidence that Thomas did anything for Crow—no quid pro quo—there is no wrongdoing and thus “nothing to see here.” I respectfully disagree. That an obligation is unspoken or implicit makes it no less significant when the obligor is a judge.

I feel like the disappointed little boy who, according to the legend, approached baseball great Shoeless Joe Jackson (lifetime batting average: .358) who had been accused of conspiring with his Chicago White Sox teammates to throw the 1919 World Series and said, “Say it ain’t so, Joe.”

Your comments are welcome.

[1] A defender of Thomas released a statement after Crow’s tuition payments for Thomas’ grandnephew came to light arguing that the payments were not reportable because a grandnephew was not a “dependent child” in the language of the reporting form. Common sense suggests that the tuition payments were a gift to Thomas.