Open Space Anomalies

A Look at Divergent Views About a Long-controversial Issue in Alexandria. From The Alexandria Times, March 16, 2023

Diametrically opposed opinions about the preservation and addition of open space in the city’s 15.7 square miles show that open space is important and subjective. Whether Alexandria, known for its density, is succeeding in maintaining and creating quality and accessible public open space is in the eye of the beholder.

The city’s overall open space target—7.3 acres per 1000 people—is not a metric that influences how residents perceive their access to quality open space. The open space target also has no bearing on whether a new commercial development provides appropriate open space.

There are anomalies, or departures from expectations, that contribute to the divergent views about open space.

“Open Space” Needs Context

The term “open space” covers extensive literal and metaphorical ground. Context is essential because open space ranges from areas close to their natural state (Taylor Run, Monticello Park, Dora Kelley Nature Park, Winkler Nature Preserve) to carefully tended small patches of grass. Market Square may be the city’s first example of public open space.

Open space includes public property (the city’s approximately 130 parks which constitute about 1,000 acres of open space), property controlled by the National Park Service (Daingerfield Island, Jones Point) and private property. Alexandria came late to acquiring land for parks: land was not purchased for the city’s first park until the 1950’s when much of its land (up to the then Quaker Lane border with Fairfax County) had already been developed.

Ecologist Kurt Moser, the co-founder of the Four Mile Run Conservatory Foundation, said that his top open space priority is preserving the city’s few natural areas:

That’s the thing we can’t replace. You could knock down a building and put a ballfield there. But you would never be able to establish a real forest there, ever. Where we have existing forests, or wetlands, meadows—we should defend those.

Natural areas are not self-maintaining. “Natural” cannot be synonymous with “impenetrable.” Invasive species, streams and wetlands, and trails or paths in natural areas all require regular attention.

Development Can Create Open Space

Casual observers might assume that the best way for the city to increase its open space inventory would be through carefully-considered real estate acquisitions. This is correct, but this strategy is severely constrained by Alexandria’s expensive land. Since 2015, the city has increasingly relied on the development process to create open space.

In 2019 officials from the departments of Planning and Zoning (P&Z); Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities (RPCA) and Transportation and Environmental Services collectively authored a planning document, Shared Expectations for Open Space in New Development, which has been adopted by the Planning Commission and the City Council.

The Shared Expectations state, “New development has an important role in the provision of public and public-private open space.” The Shared Expectations also highlight the importance of non-public open space: “Private open space is a necessary and positive component of open space in new development projects” and confirm that above-grade open space, “can be a valuable contribution to on-site open space.”

Many arguments about open space are over the ways and extent that developers are asked to contribute to the city’s stock of open space as a condition of securing necessary city approvals. Some development projects, for example, the conversion of an office building to residences, cannot dedicate property to open space because the site is already completely built out. The Shared Expectations state that in such a case a developer, “will be required to provide contributions (in-kind contributions or funds toward shared public open spaces such as parks)” according to criteria established in the city’s Small Area Plans.

How to Count Developer Open Space

The City Council created the Open Space Steering Committee (OSSC) to, according to the city’s website, “assist staff in the development of an Open Space Policy Plan.” Moser is a Co-Chair of the OSSC. The OSSC is expected to recommend changes by April to the city’s open space policies, to how the city acquires open space, and how developer open space contributions should be counted.

City officials have not been making up the rules as they went along for reviewing open space contributions by developers. However, defining the criteria for such contributions is not easy and the process of doing so—part of the OSSC’s work—is not complete.

Section 2-180 of the city’s Zoning Ordinance defines “open and usable space,” but it does not address the complexities involved in developer open space contributions. Section 2-180 provides:

Open and usable space

A) Eight feet or more in width;

B) Unoccupied by principal or accessory buildings;

C) Unobstructed by other than recreational facilities; and

D) Not used in whole or in part as roads, alleys, emergency vehicle easement areas, driveways, maneuvering aisles or off-street parking or loading berths.

The purpose of open and usable space is to provide areas of trees, shrubs, lawns, pathways and other natural and man-made amenities which function for the use and enjoyment of residents, visitors and other persons.

Karl Moritz, Alexandria’s Planning Director, describes the evolution of open space as a city infrastructure priority:

[W]e've become interested in the qualities of the open space provided. In the development of single-family neighborhoods (and that era is largely behind us), private open space (i.e., yards) was very much the norm and people tended to look at public open space (i.e., parks) as something government would provide. As the majority of new residential development became multifamily, planners developed rules of thumb for ensuring that the open space required by the zoning ordinance met multiple needs: the needs of the residents of the new multifamily building, the need to separate large buildings and provide light and air, the contribution of new development to shared (that is, public) open space, etc.

Development projects are location-specific—what may work as open space for one project is not feasible for another. How, and whether, above-grade (usually rooftop) areas should count as open space has been a point of contention. Moritz said:

Periodically staff would hear comments at [a] hearing that 100% of the open space provided by a new apartment building should be ground floor and accessible to the public. So, we thought it would be useful to have a discussion about the goals we have for the open space required by the zoning ordinance, and that discussion resulted in "shared expectations."

Some projects, for example, the Harris-Teeter store in North Old Town, cannot generate additional physical open space. In that instance there were developer cash contributions to improve nearby parks.

No Dedicated Open Space Funding

One of the audience questions at the November 29, 2022 Agenda: Alexandria meeting on open space was, “How much money is in the Open Space Fund?”

The Open Space Fund was created in 2003 and funded by the dedication of $.01 of the real estate tax rate. In 2007, the funding arrangement was changed to 1% of the revenue generated from real property taxes.

Former Mayor Allison Silberberg was the city’s Vice Mayor in May 2013 when the City Council voted to eliminate dedicated funding for open space. Silberberg was the lone dissenting vote in a 6-1 decision. Silberberg’s frustration with the elimination of dedicated funding for open space, and how it was done, has not diminished in the nearly 10 years since the vote. That frustration is evident in a May 30, 2013 column, “A tale of two funds” she wrote for the Alexandria Times which can be viewed at https://alextimes.com/2013/05/a-tale-of-two-funds/

Silberberg wrote:

If the public had known about this possible change, then residents would have had time to respond and write [to] us, just as they did about the Warwick pool, the meters in Old Town, the schools, etc. Not one email came in about these two funds because no one new about a possible change.

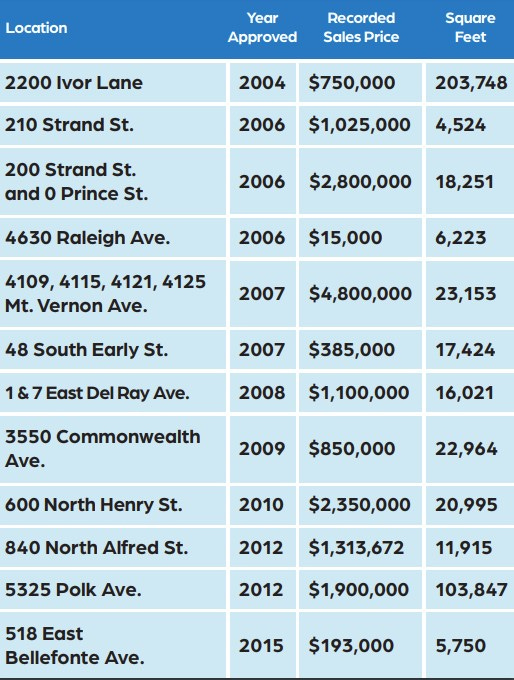

Here is a summary of city open space acquisitions from 2004 through 2015:

The large expenditures in 2006 ($2.8 million) and 2007 ($4.8 million) were for the Old Dominion Boat Club property and the expansion of Four Mile Run Park. Since 2015, the city has reduced its land acquisition expenditures for public open space.

Jack Browand, RPCA Deputy Director, explained at Agenda: Alexandria that the Open Space Fund is now a Capital Improvement Program (CIP) line item:

When the city had to respond to the economic downturn, that dedicated contribution was eliminated. We still have an Open Space Fund but it is 100% funded by the city. It’s a general fund account in the capital improvement [program] and it ranges from several hundred thousand up to a million dollars per year and sometimes it’s larger. It’s part of the budget process.

Thus, open space land purchases compete with every other capital budget priority, including school capital funding and necessary city facility repairs, in the CIP. The FY2022-2031 10-year CIP includes $10 million for open space.

There are several reasons for the decline in city-funded open space acquisitions in the last 7-8 years. These include the city’s 2012 financial retrenchment, increasing financial demands relating to other priorities, and an assessment that the city’s overall open space goal (7.3 acres per 1000 people) is likely to be met for at least the near future.

Open space has also been funded by other sources. For example, Woodrow Wilson Bridge settlement funds paid for Witter Field and the Contraband Freedmen’s Cemetery acquisition.

Looking Ahead

Two large projects at either end of the city—West End Alexandria at the former Landmark Mall site and the development at the former Mirant power plant site on the Potomac—will be particularly important to Alexandria’s open space future.

Open space is an essential part of the city’s infrastructure for numerous reasons. Jeff Farner, P&Z’s Deputy Director, said, “In a diverse city, open space is where everyone mixes. All races and ages mix there.”

Silberberg points to open space as part of the strategy for addressing climate change, a problem which has grown in the almost 10 years since dedicated open space funding was ended. She said, “All of us need open space for all kinds of reasons.”

-aboutalexandria@gmail.com