Literary Dude: William Butler Yeats and "The Second Coming"

How, in 1919, an Irish poet defined the central anxieties of our time.

The Second Coming

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: a waste of desert sand;

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Wind shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

--1919

If the pandemic, climate change, Ukraine, the Middle East, etc. suggest a societal Great Unraveling, then it is modestly comforting to know that Irish poet William Butler Yeats confronted the same feelings of social entropy and dread of what comes next over a hundred years ago.

Yeats, considered one of the greatest poets in the English language, wrote “The Second Coming” in 1919 when England and Europe were in the upheaval of World War I and a flu pandemic (which nearly took his wife’s life) was raging. “The Second Coming” resonates today.

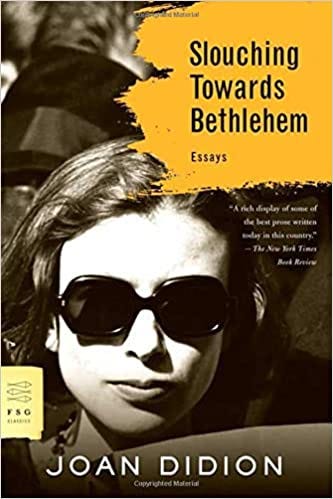

Yeats (pronounced “Yates” even though another English poet, John Keats, is “Keets”) captured the sense of entropy, or a gradual decline into disorder, in “The Second Coming.” Other writers chronicling disintegrating communities or societies have borrowed phrases from the poem, notably Chinua Achebe in his novel Things Fall Apart and Joan Didion in her essay collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

Long time (and masterful) New Yorker cartoonist George Booth also used a line from the poem:

The poem begins with six measured couplets that describe the circular path, or gyre, of the falcon that is now beyond the hearing of the falconer. The “mere anarchy” with its “blood-dimmed tide” that is “loosed upon the world” builds to the second stanza’s introduction of the “vast image out of Spiritus Mundi,” or spirit of the world. That spirit has become so degraded that the “second coming” is the antichrist, a sphinx figure: “A shape with lion body and the head of a man.”

“The Second Coming” shows Yeats’ careful use of enjambment—the spilling over of a sentence from one poetic line to the next without any terminal punctuation. Enjambment stresses the last word in the line by providing a frame of space and a microsecond pause before the reader’s eye moves to the next line. For example, the enjambed fifth and seventh lines of the first stanza end with the words “everywhere” and “worst”—an accurate summary of the stanza’s essential meaning.

In the last stanza the speaker realizes that “twenty centuries of stony sleep” or 2,000 years, have become a nightmare as a child has nightmares from a rocking cradle. Something uncertain, a “rough beast” is unhurriedly slouching its way to Bethlehem to be born where Christ was born. In Yeats’ dark vision the descent into social chaos means that something cataclysmic is on the way; we just do not know what it is.

Yeats was also committed to writing about Ireland and national identity. He said, “I should never go for the scenery of a poem to any country but my own, and I think I shall hold that conviction to the end.” He was a fervent Irish nationalist and even served six years in the Senate, the Dáil Éireann. Of Ireland, Yeats said, “We are a nation of believers.”

As a child, he was homeschooled and then sent to art school to follow in the footsteps of his father, a famous portrait painter. One of his report cards said, “Perhaps better in Latin than in any other subject. Very poor in spelling.” Undeterred, he quit art school and devoted himself to poetry. His collections include In the Seven Woods (1903), Responsibilities (1904), and The Green Helmet and Other Poems (1910.)

Yeats became famous in his lifetime. Poet Ezra Pound became his secretary for a time when they shared a cottage in Sussex for several months. Yeats cut a dashing figure in London. A friend said, “Yeats was striding to and fro at the back of the dress circle, a long black cloak drooping from his shoulders, a soft black sombrero on his head, voluminous black silk tie flowing from his collar, loose black trousers dragging untidily over his long, heavy feet.”

Yeats met the great, unrequited love of his life, Maud Gonne, in London. She was tall, beautiful, devoted to Irish nationalism, and did not return his affections. He wrote several plays for her including The Countess Kathleen (1892) and Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), in which Gonne played the starring role. Yeats proposed to her three times over several decades and each time she refused. The last time she rejected him, he proposed to her daughter, who said no, as well. When Yeats met Maud Gonne, he famously said, “The troubles of my life began.”

At 52, he married Georgie Hyde-Lees and had two children. They lived in a tower on the outermost edge of Ireland and practiced spiritualism. Yeats had many lovers over the years, but Georgie forgave him.

His other notable poems include “Easter, 1916,” “Sailing to Byzantium,” and “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” He won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1923.