Literary Dude: Raymond Chandler and The Long Good-bye

Why a detective novel published more than 70 years ago still matters

The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic and a killer. It has never yet melted.

- D.H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature

D.H. Lawrence’s very British assessment of the core elements of the American character seemingly explains conditions such as the epidemic of gun violence or the rise of MAGA-related isolationism in foreign affairs or reduced participation by Americans in community organizations. However, Lawrence was writing about American literature, and literature is more fun than national pathologies.

Some of Lawrence’s observations are confirmed in Raymond Chandler’s 1953 noir novel, The Long Good-bye. The book is fascinating, and moving. It is hard-boiled detective fiction, but it is unexpectedly about the compassion and friendship shown to the dissolute Terry Lenox by the narrator, Philip Marlowe, a tough and stoic Los Angeles private investigator.

Why Detective Fiction Matters

For many years, detective fiction was in the down-market section of American literature’s department store—it was not accorded the respect given to “serious literature.” Detective fiction is plot and character driven and usually light on themes involving social conditions or big ideas. The genre often employs slang, which does not age well. When was the last time a gun was called a “gat” or someone encouraged a person to talk by saying, “Spill”?

The emphasis on plot and character in detective fiction may account for the enthusiasm with which moviemakers have embraced it. The Big Sleep, The Maltese Falcon, Chinatown are among the classic films that feature detectives who work alone. [1]

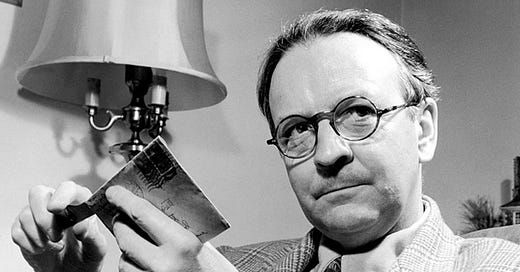

The appreciation of Chandler’s work by academic authorities may have been slow in coming, but Chandler’s writing offers many reading pleasures. [2] Chandler, an exceptional prose stylist, renders the notion of “guilty pleasure reading” obsolete. There is only great writing and Chandler’s work qualifies. The following is an appreciation of The Long Good-bye and, just for fun, some additional thoughts.

Why the The Long Good-bye Matters

Possibly Chandler’s masterwork, The Long Good-bye turned 70 last year and is the last of his novels featuring Los Angeles private investigator Philip Marlowe. Marlowe is surprisingly compassionate and generous in his accidental friendship with Lennox, a shiftless drunk.

Marlowe describes Lennox in the novel’s first line which is worthy of anything by Jane Austen or Herman Melville: “The first time I saw Terry Lennox he was drunk in a Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith outside the terrace of The Dancers.”

Marlowe sobers up Lennox and they begin a casual friendship. Lennox’s heiress wife, Sylvia, is brutally murdered and Marlowe is sure that Lennox is not the killer. Lennox hires Marlow to drive him to Mexico. Marlowe’s commitment to ascertaining whether Lennox murdered his wife, and whether Lennox subsequently died by suicide in Mexico, drives the novel.

Marlowe navigates a Los Angeles of money, power, deception and self-hatred. Along the way we meet rich and bored women, aggressive cops with borderline ethics, scheming lawyers, corrupt doctors, mobsters, and a grasping publisher who wants a final book from an anguished and declining writer. Marlowe moves easily in wealthy Los Angeles neighborhoods and in the city’s underworld.

It is not an accident that two of the actors who portrayed Philip Marlowe in the movies are the enduring Humphrey Bogart and Robert Mitchum:

Chandler’s Descriptive Powers

Chandler’s powerful descriptive writing is succinct and efficient. Here is Marlowe telling us where he lives:

I was living that year in a house on Yucca Avenue in the Laurel Canyon district. It was a small hillside house on a dead-end street with a long flight of redwood steps to the front door and a grove of eucalyptus trees across the way. It was furnished, and it belonged to a woman who had gone to Idaho to live with her widowed daughter for a while. The rent was low, partly because the owner wanted to be able to come back on short notice, and partly because of the steps. She was getting too old to face them every time she came home. (3)

In five plain sentences Chandler locates Marlowe in hilly, quiet and wooded Laurel Canyon and shows that he inclines to numerous (“that year”) and uncomplicated (“furnished”) and thrifty (“The rent was low”) living arrangements. Marlowe is no homebody. The long flight of redwood steps is not an accident—the steps figure in subsequent scenes. Move over, Ernest Hemingway.

Marlowe is man of long experience and no delusions. Here he is describing his return drive to Los Angeles after driving Lennox to Mexico:

It’s a long drag from Tijuana and one of the dullest drives in the state. Tijuana is nothing; all they want there is the buck. The kid who sidles over to your car and looks at you with big wistful eyes and says, ‘One dime, please mister,’ will try to sell you his sister in the next sentence. Tijuana is not Mexico. No border town is anything but a border town, just as no waterfront is anything but a waterfront. San Diego? One of the most beautiful harbours in the world and in it nothing but navy and a few fishing boats. At night it is fairlyland. The swell is as gentle as an old lady singing hymns. But Marlowe has to get home and count the spoons. (41)

Marlowe seems to talk to us out of the side of his mouth. His anecdotes convey his worldly experience with border towns and waterfronts and his jesting idiom (“count the spoons” dates from the 1840’s) illustrates his cynical attitude about the departure of the untrustworthy Lennox.

Speaking Truth to Wealth and Power

The Long Good-bye’s many joys include razor sharp dialogue. A private eye, Marlowe represents himself without any police-community relations faux courtesy. Marlowe tells off police officials, mobsters, and the great and powerful of Los Angeles with equal force and effect.

Here is Marlowe talking to the powerful and manipulative Los Angeles business titan, Harlan Potter [4]:

I got your point all right, Mr. Potter. You don’t like the way the world is going so you use what power you have to close off a private corner to live in as near as possible to the way you remember people lived fifty years ago before the age of mass production. You’ve got a hundred million dollars and all it has brought you is a pain in the neck. (276)

Marlowe is “isolate” in D.H. Lawrence’s terms because he lacks organizational connections and restraints—he reports to nobody and nobody reports to him—which gives him the freedom to say exactly what he thinks in blunt ways. Many of us lead lives filled with compromises; it is fun to watch Marlowe move through life on his own terms.

Marlowe reserves special contempt for people who are not genuine. Marlow talks back to the evil hoodlum Mendy Menendez even as Menendez beats him up and threatens to kill him:

‘Lennox was your pal,’ I said, and watched his eyes. ‘He got dead. He got buried like a dog without even a name over the dirt where they put his body. And I had a little something to do with proving him innocent. So that makes you look bad, huh? He saved your life and he lost his, and that didn’t mean a thing to you. All that means anything to you is playing the big shot. You didn’t give a hoot in hell for anybody but yourself. You’re not big, you’re just loud.” (410)

Moral Choices, Big and Small

Menendez tries to insult Marlowe by calling him “cheapie.” It does not work. Marlowe’s attitude about money and his refusal to be bought are central to his identity.

Marlowe charges Lennox $500 and a gun to drive him to Mexico. Lennox subsequently sends a $5,000 bill [5] to Marlow who keeps it in his safe. Describing the eventual disposition of the $5,000 bill would be a spoiler. However, that disposition is consistent with what we know about Marlowe who is described by another character in a climactic scene as having, “no price tag.”

The ultra-wealthy Potter is inconvenienced by Marlowe’s investigation and wants to buy Marlowe off. He asks, “What do you want from me, Marlowe?” Marlowe responds, “If you mean how much money, nothing.” (277)

Marlowe’s attitude about money recalls that of Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon. Spade, played by Humphrey Bogart, deprecates the Maltese Falcon, an item of supposedly inestimable value that almost everyone in the movie chases, by calling it, “the dingus.”

Fidelity to the truth is another trait that makes Marlowe fascinating. Marlowe’s loyalty is not to a person or persons or an organization. Marlowe is not focused on “my truth” in today’s phrase. Rather, Marlowe is dedicated to the truth as an objective ideal—the most accurate version of what actually happened.

Marlowe’s obsession with the truth and his refusal to be bought off are a powerful combination. Here is Marlowe explaining things to Potter just before Potter tries to buy him off:

That’s all there is, there isn’t any more. You don’t care who murdered your daughter, Mr. Potter. You wrote her off as a bad job long ago. Even if Terry Lennox didn’t kill her, and the real murderer is still walking around free, you don’t care. You wouldn’t want him caught because that would revive the scandal and there would have to be a trial and his defence would blow your privacy as high as the Empire State Building. Unless, of course, he was obliging enough to commit suicide, before there was any trial. Preferably in Tahiti or Guatemala or the middle of the Sahara Desert. Anywhere the County would hate the expense of sending a man to verify what had happened. (275)

The contrast could not be clearer: unlike Potter, Marlowe cares about discovering who killed Sylvia Lennox, cares about whether the real murderer is walking around free, cares about whether Lennox died by suicide, and does not care if the facts come out. Marlowe is a man with clear principles and he lives by those principles.

Marlowe knows how to stay on the right side of the law, but he delights in insulting the police. Marlowe’s counterpart from the contemporary underworld might be The Wire’s Omar Little (Michael K. Williams.) Omar robs drug dealers, but he follows his own rules which include not using, “my gun on people not in the game.” D.H. Lawrence’s description—“hard, isolate, stoic and a killer”—seems to fit Omar.

In this scene Omar explains how his world works to Detective Bunk Moreland (Wendell Pierce) of the Baltimore Police Department. Omar, a fatalist, tells Moreland that he will probably be “seeing God,” or dead, before he takes an oath before God and testifies in court. Moreland tells Omar that even if he is not guilty of the crime (Moreland describes it as a “taxpayer murder with an eyeball witness”) for which he has been arrested, Omar is surely guilty of numerous other serious crimes.

Omar acknowledges what he has done, but points out that if he is convicted for an offense he did not commit an injustice occurs because the guilty party escapes punishment. Omar reminds Bunk, “A man got to have a code.”

Why Loaners With Codes Fascinate Us

Joan Didion describes our enduring fascination of characters like Philip Marlowe and Omar Little in her essay, 7000 Romaine, Los Angeles 38 [6]:

Our favorite people and our favorite stories become so not by any inherent virtue, but because they illustrate something deep in the grain, something unadmitted.

If you have read this far, thank you. I hope you will consider reading The Long Good-bye, a wonderful addition to the narratives of American loners who live by moral codes.

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] Pauline Kael’s 1973 review of Robert Altman’s movie version of The Long Goodbye quotes highbrow critic Edmund Wilson who describes his “old crime-story depression.” For Wilson, detective fiction, “…fails to justify the excitement produced by the picturesque and sinister happenings, and I cannot help feeling cheated.” Kael’s review can be seen

[2] Detective fiction’s close relative, crime fiction, has also gained increasing respect from literary authorities. The Library of America publishes hardcover anthologies of works by writers who are deemed worthy, thus becoming a kind of cultural gatekeeper. Crime fiction master Elmore Leonard’s novels (Get Shorty, Be Cool, Riding the Rap, and many others) have been published by the Library of America. Leonard’s best-known character is Deputy U.S. Marshall Raylan Givens who resembles Marlowe with a badge. More about Leonard is available

Collections of Chandler’s novels have also been published by the Library of America and can seen

[3] All page citations are to The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler, Penguin Books, 2010.

[4] Perhaps Harlan Potter is related to Henry F. Potter (played by Lionel Barrymore), the businessman who dominates Bedford Falls in Frank Capra’s movie, It’s a Wonderful Life.

[5] About $57,000 in today’s dollars.

[6] Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion, Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1968, p. 71.

I never thought before about reading this book--but now I do want to read it!

Thank you Literary Dude. I will add this to my summer reading stack!