Every time a Cooper person is in peril, and absolute silence is worth four dollars a minute, he is sure to step on a dry twig. There may be a hundred handier things to step on, but that wouldn’t satisfy Cooper. Cooper requires him to turn out and find a dry twig; and if he can’t do it, go and borrow one. In fact, the Leather Stocking Series ought to have been called the Broken Twig Series.—Mark Twain on James Fenimore Cooper

The Lincoln of Our Literature

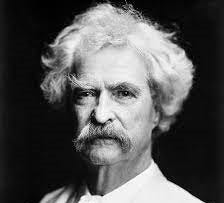

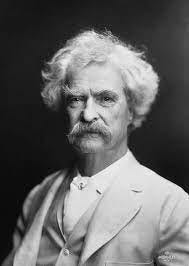

American author and critic William Dean Howells (1837-1920) called Mark Twain, “the Lincoln of our literature.”

Howells’ compliment is about the highest possible praise, and Twain is still very much with us. Since 1998, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts has awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor to “…individuals who have had an impact on American society in ways similar to the distinguished 19th-century novelist and essayist Samuel Clemens, best known as Mark Twain. As a social commentator, satirist, and creator of characters, Clemens was a fearless observer of society, who startled many while delighting and informing many more with his uncompromising perspective on social injustice and personal folly.” Information on the Mark Twain Prize, and its recipients, is available

Howells’ Lincoln-Twain comparison extends to the lively sense of humor that each man possessed. Lincoln, of course, was constrained by the need to be seen as a statesman, but there are extensive accounts of his fondness for jokes. Historians have written that Lincoln was belatedly invited to make remarks at the ceremony at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania because it was feared that he would not be sufficiently serious or somber. Twain, however, gave free reign to his gift for humor, particularly when he could aim it at other writers whose reputations or work he considered overblown.

Twain’s sense of humor is evident in novels (Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) and short stories (The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County) and in his very successful career as a traveling lecturer. The late Hal Holbrook portrayed Twain as a speaker in his long-running one man show, Mark Twain Tonight!

Twain’s willingness to make fun of other writers, including eminent authors, is evident in an 1898 letter describing his opinion of Jane Austen’s (1775-1817) classic novel, Pride and Prejudice. Twain wrote, “I have to stop every time I begin. Every time I read ‘Pride and Prejudice’ I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone.”

Twain was a widely-traveled and sophisticated man who delighted in posing as an uncouth character. Whether his loathing of Jane Austen’s work was genuine or professed for comic effect is debatable, but there seems to be little doubt that Twain was at his funniest when he posed as a literary critic.

So, in these anxiety-filled times when a good laugh is a valuable thing it is worth pausing to enjoy Twain’s 1895 essay, Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses, which appears in numerous anthologies and can be read

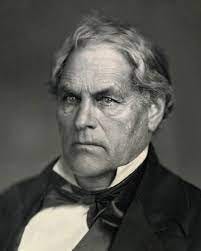

Twain Takes on James Fenimore Cooper

Cooper was a successful author of historical romances featuring colonial and indigenous characters. Cooper’s fictional scout, Natty Bumppo, appears in several of his books. Cooper’s romantic vision of the American frontier is evident in The Pioneers (1823), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), The Prairie (1827), The Pathfinder (1840), and The Deerslayer (1841) which are collectively called the Leatherstocking Tales. Cooper’s reputation, and his success, made his works an inviting target for Twain.

Cooper’s writing owes much to Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), author of The Scarlet Letter, Young Goodman Brown and other works. This passage from The Deerslayer exemplifies Cooper’s elaborate descriptive style:

The arches of the woods, even at high noon, cast their sombre shadows on the spot, which the brilliant rays of the sun that struggled through the leaves contributed to mellow, and if such an expression can be used, to illuminate. It was probably from a similar scene that the mind of man first got its idea of the effects of gothic tracery and churchly hues, this temple of nature producing some such effect, so far as light and shadow were concerned, as the well-known offspring of human invention.

It is difficult to imagine Twain writing this way. As a writer, Cooper was of his time, but Twain’s works, particularly Huckleberry Finn, show that he was of his time and is highly relevant in our time.

Twain begins Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences by quoting extravagant praise for Cooper’s works by professors at Yale and Columbia and by a critic, Wilkie Collins. The essay draws us in this way:

It seems to me that it was far from right for the Professor of English Literature in Yale, the Professor of English Literature in Columbia and Wilkie Collins to deliver opinions on Cooper’s literature without having read some of it. It would have been much more decorous to keep silent and let persons talk who have read Cooper.

Twain’s understated and effective word choice (“decorous”) and the sly suggestion that the literary experts would not praise Cooper’s work as they did if they had read it launches the essay. More devastating understatement follows:

Cooper’s art has some defects. In one place in ‘Deerslayer,’ and in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offences against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.

Only Mark Twain could describe 114 out of 115 “offences against literary art” in two-thirds of a page as “some defects.” It is hard to read Twain’s essay without laughing, audibly or otherwise.

Was Twain being mean to the deceased Cooper to score a few cheap laughs? There is a comedic intent to Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offences but the essay also signifies Twain’s revolt as a modern artist against the work of a romantic traditionalist, Cooper.

T.S. Eliot, a modernist by any standard, wrote an introduction to a 1950 edition of Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which praises the novel’s stylistic “innovation.” For Eliot, Twain’s “new discovery” is the creation of “natural speech in relation to particular characters” without a single “sentence or phrase” compromising the illusion of each character’s voice. Twain’s characters sound completely authentic and true to themselves and not like figures in a romanticized vision of the American frontier. More about Mark Twain as a modernist writer can be seen

Why Huckleberry Finn Still Matters

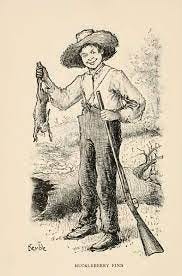

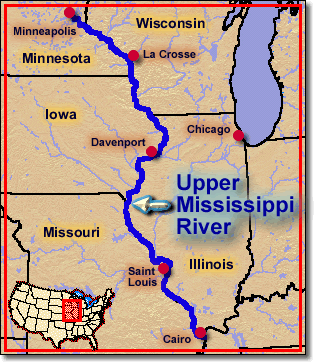

After years of start-and-stop work, Twain completed Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1884. The heart of the book are the adventures on a raft trip down the Mississippi River by the runaway slave, Jim, and the wise-beyond-his years Huck. The raft trip, in about 1835[1], transports us in many ways. Huck and Jim have a series of encounters that involve philosophy, social observation, the nature of friendship, humor and race relations.

“All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn,” said Ernest Hemingway, calling it, “the best book we’ve had … There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.” Yet, Huckleberry Finn is among the most banned books in schools and a controversy continues over whether the n-word, which appears 219 times in the novel, should be replaced with “slave” or a similar word.

The American Library Association has designated Huckleberry Finn as one of the “most challenged” books. The irony in the attempts to ban Huckleberry Finn or “update” Huck’s language to align with modern sensibilities is that Huck repeatedly makes decisions involving his relationship with Jim, and about how he and Jim deal with race in America, that almost anyone would think of as enlightened or progressive.

Huck, about 13, lacks formal education (his father, Pap, a mean drunk, does not want him to go to school) but the lessons he teaches in his acts and words are profound. Even more impressive, there is nothing teacherly about what he does—he lives life as it comes.

Huck’s crisis of conscience—the book’s moral center—occurs in Chapter 31 when Jim is held captive and Huck decides to write Miss Watson, Jim’s owner, a letter telling her where Jim is so that Jim, her property, can be returned to a life of slavery. Huck writes the letter and then tells us:

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray, now. But I didn’t do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking; thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me, all the time, in the day, and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storm, and a floating along, talking, and singing, and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind.

Huck sees the letter and says:

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“All right, then, I’ll go to hell”—and tore it up.

Huck’s decision to “go to hell”—to defy the legal conventions associated with the slavery system —demonstrates Twain’s literary genius. The novel is a masterpiece of language, plot and character. About 20 years after the Civil War and roughly a century before the dawn of the Civil Rights movement, Twain has Huck condemn America’s pervasive racial inequality in compelling moral terms understandable to everyone.

A Brief Guide to Enjoying Huckleberry Finn

Those who have never read Huckleberry Finn, or who have not read it recently, have a treat in store. Here are a few suggestions. An English teacher in your service area may have additional recommendations.

Make Sure Your Copy of Huckleberry Finn Includes Edward W. Kemble’s Illustrations. Huckleberry Finn has long been in the public domain and the novel is available at all price points. The first edition of the book included extensive illustrations by the self-taught artist, Edward W. Kemble (1861-1933.)

Kemble, who was personally selected by Twain, was only 23 when he illustrated the novel. More about Kemble is available

And, for fabulous further reading, there is Michael Patrick Hearn’s lavishly illustrated and endlessly interesting 480-page annotated version of the novel.

The annotated version is a wonderful gift for a family member or friend. Information about it is available

Do Not Become Dispirited or Annoyed About How the Characters Speak. Twain had a remarkable ear for dialect. Huckleberry Finn includes this “Explanatory:”

In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods South-Western dialect; the ordinary “Pike-County” dialect; and four modified varieties of this last. The shadings have not been done in a hap-hazard fashion, or by guess-work; but pains-takingly, and with trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.

I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.

Anyone who encounters difficulty with the accents of the characters in Huckleberry Finn needs only to read the dialogue aloud—it will be immediately understandable.

Huck and Jim Miss the Turn at Cairo. In Chapter XVI, Huck and Jim are nearly killed by a steamboat and are thrown from the raft. In the confusion, they pass by the Ohio River and continue down the Mississippi, a crucial event that is not completely clear in the book.

By missing the chance to sail the raft up the Ohio River to the free states Huck and Jim create a duality: as they run away from Missouri and Jim’s enslavement they are also running toward New Orleans, the center of slavery and a place of great peril for Jim.

Why the Phelps Farm Section of Huckleberry Finn Matters. Critics have denigrated the post-raft trip section of the book when Tom Sawyer reappears as “irrelevant” (Philip Young) and a “flimsy contrivance” (Leo Marx.) Tom proposes elaborate schemes to free Jim from captivity on the Phelps farm and Huck seems to become a bystander.

The speculation that Twain did not know how to end the book is unwarranted. Matt Zahn, an accomplished English teacher, sees the Phelps farm section this way:

Huck has just traveled with Jim through the dark and treacherous heart of the American South, and he has emerged better. The trip, and the book, have been picaresque in the best way. The writing is not overtly moralizing, but it seems so obvious that the adults in the American South have lost their way just as Huck is finding his. They adhere to strict codes, slavery chief among them, without justification or morality. Huck can still be impish and rebellious, but now he now knows what he's rebelling against.

The ending of the book - specifically the 'freeing' of Jim - turns a critical eye toward the abolitionist North and its motivations. While Huck has vowed to free Jim from the Phelps family and risk going to hell for it, Tom Sawyer sees an opportunity to come up with a plan for personal glory. It's not enough to simply free Jim (and there are ample opportunities to do so). Tom wants an elaborate ruse that makes him the savior. While the rest of the book is a clever and frequently caustic indictment of the American South, it is an easy target. The final section of the book criticizes the savior complex of the abolitionist North and their (and, sometimes, our) need for recognition as allies and heroes. Twain uses this section to suggest that Jim shouldn't be saved because of what he represents. He should be saved because he's human.

Final Thoughts. Thank you for reading this far. If you might explore, or return to, Twain’s work, then this post is a success.

Twain seems to be the most American of authors—a kindred spirit or neighbor to us all. Here is my connection to him.

My father, who was born in 1922, told me that when he was a boy in Minneapolis his family would periodically see an elderly lady whom he knew as Ms. Wallace. She was rumored to have known Mark Twain.

The rumors were true. Elizabeth Wallace (1865-1960) met Mark Twain in Bermuda in 1908 and for the last two years of Twain’s life they exchanged books and letters, and celebrated Thanksgiving together. In 1923, Wallace and two others became the first women to be named full professors at the University of Chicago. She seems to have known everyone. As one chronicler wrote:

After her University of Chicago career ended, Wallace stayed active until her death in 1960—as a scholar, attending academic conferences all over the world, and as the Zelig-like figure she’d long been, crossing paths with a colorful cast of writers and intellectuals. Among those she encountered, (both during and after her UChicago career) were Henri Bergson, Marc Chagall, Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James, Emile Zola, Diego Rivera, Leon Trotsky and Edith Wharton.

More about Elizabeth Wallace is available

So, while I did not know Mark Twain, I knew someone who knew someone who knew him.

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] The title page of the book states “Scene: The Mississippi Valley” and “Time: Forty to Fifty Years Ago.”