Leaving the Election Postmortems Behind

How to Read Explanations of the 2024 Election Results and What to Do Next

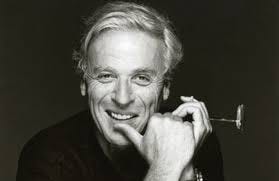

What William Goldman Knew

William Goldman, an extremely successful screenwriter (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, The Princess Bride), famously explained Hollywood by saying, “Nobody knows anything.”

Goldman’s point was that that movie success is unpredictable and unexplainable. He amplified on his three-word maxim in his bestselling 1989 book, Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting: “Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what's going to work. Every time out it's a guess and, if you're lucky, an educated one.”

Goldman’s explanation of Hollywood is worth keeping in mind when sorting through the many published explanations of the results of the 2024 presidential election. Columnists and other opinion merchants have expended substantial time and effort to explain what happened on November 5. Many of the explanations fall into recognizable types.

Each analysis of the election’s results, while entertaining and sometimes compelling, fails at what physicists call a unified field theory—an explanation of all the fundamental forces and relationships in a single theoretical construct that explains a condition or phenomenon. When it comes to elections, there is no “Theory of Everything.”

Lawyers refer to “proximate cause,” a cause which in a direct sequence produces an event or condition and without which such event or condition would not have happened. A national election may be the ultimate proximate cause-driven event: tens of millions of voters cast ballots for their individual reasons. What follows are descriptions of four of the most prominent election postmortem styles and suggestions for moving forward.

The Blamethrower

A flamethrower projects a controllable fire jet. A similar effect is evident in post-election analyses that blame a single individual or group, for example, the Democratic Party. “This is All Biden’s Fault” ( Josh Barro in The New York Times, Nov. 11), which can be seen

is an example of the blamethrower approach. Training concentrated fire, or blame, on a single target may provide visceral satisfaction, even a score, or ease the disappointment of an electoral loss. However, this approach inevitably generates “Well, what about [insert equally plausible explanation(s) here]?” questions.

Demographic Slicing and Dicing

Another post-election explainer involves an assessment, usually framed by comparisons to previous elections, of the voting patterns of a particular demographic or ethnic group in a critical state. This approach involves an “if only” conditional statement, as in “If only [Latino voters in Pennsylvania] [Arab-American voters in Detroit] [Insert voting group and region of your choice here] had voted as they did in [Insert prior election here] everything would have been fine.” Registration authorities do not maintain data sorted by voter age or ethnicity, so this approach relies primarily on exit polling. Exit poll respondents know that they can lie or fail to respond to pollsters without consequence. If it is disappointing pollsters underestimated President Trump repeatedly, why should we think that exit polling is any more accurate? Moreover, there is no assurance that a different demographic or ethnic group did not have a comparable, or even more profound, effect on the election results.

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars”

In Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar, Cassius says, “Men at some time are masters of their fates:/The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, /But in ourselves, that we are underlings.” Cassius argues that collectively we control our fate, but some people, like Caesar, are more influential than others. The inward looking (or the-answer-is-within-us) stance is a time-tested election postmortem. A call for self-examination, whether from a political party or the entire country, always seems thoughtful. An example of this approach is “Voters to Elites: Do You See Me Now?” (David Brooks in The New York Times, Nov. 6) which is viewable

Brooks calls for introspection and change from people characterized as America’s educated elite who, he argues, ignored the hollowing out of communities in the middle of the nation as a result of the decline in manufacturing, free trade policies, immigration, opioids, and the flight of capital and people to the East and West Coasts.

Rolling in the Deep Data

Elections generate data points that can be compared with each other and with data from prior elections. Number crunching at a granular level is a prominent explanatory technique for election results. Consider the following analysis of the Michigan results:

The damage for Harris was particularly dire in Wayne, the state’s largest county. Four years ago, Biden carried it 68%-30%, a margin of 332,617 votes. Harris, though, only won Wayne by 29 points, a margin of 247,803 votes. That’s a net reduction of about 85,000 votes for Democrats from their biggest single source of votes on the map. (Steve Kornacki, NBC News, “The Key Voter Shifts that Led to Trump’s Battleground State Sweep,” Nov. 17.)

Numbers are endlessly interesting, and Kornacki’s state-by-state analysis can be seen

This postmortem approach understands the results of a national election through the outcomes of voting subgroups, often, as in this example, at the county level. That Wayne County’s voters cast about 85,000 fewer votes for Vice President Harris than they did for President Biden in 2020 is important, but why this happened remains open to interpretation. And, if statistics are described as showing that elections are “won at the margins,” that idea should be permanently retired along with the observation that “this election represents an inflection point.” Each of these ideas is a cliche′ and devoid of real meaning.

Now what?

It is not an accident that national election results often include, or are closely connected to, advice about how to manage what comes next. Advice for coping with this year’s election results ranges from organized political and social resistance (“Here’s the Plan to Fight Back,” Senator Elizabeth Warren in Time magazine, Nov. 7) to advanced self-care techniques ( “How to Get Through Election Day,” Mark Leibovich in The Atlantic magazine, Nov. 4.)

Election explaining is an exercise in assumptions, inferences and hypotheticals. A fairly small number of people—elected and party officials, consultants, and other political professionals—have the means to influence national politics. At the national level, most of us are political onlookers, no matter how astute we are or think we are.

Explaining election results is an attractive parlor game (even though parlors are unfashionable) for opinion writers and politics nerds because everybody can win and nobody must lose—all election outcome explanations have an element of plausibility, but none is definitive, final, or unchallengeable. But the game is about what happened, not about what we can or should do now.

The respectful suggestion here is that the appropriate and effective way to react to the 2024 election results is to be the best Alexandrians we can be, that is, to double down on local advocacy and commitment. This is work for the long run, not just election to election. No matter how we vote, there is no guarantee that our beliefs and principles will ever govern federal policies.

What we might do in Alexandria involves recognizing and using the resources we have independently, such as:

● Supporting, financially or through direct action, the City’s difference-making organizations such as the Alexandria Tutoring Consortium, Meals on Wheels, Carpenter’s Shelter, Community Lodgings, and ACT for Alexandria.

● Applying for a position on any of the City’s numerous boards, commissions and task forces.

● And, since elections are top of mind, urging the new Mayor and City Council to organize a community forum or discussion to seriously consider staggered election terms and other electoral reforms. Former City Councilor and General Assembly member David Speck said, “Staggered terms create timely, real debate on issues and give candidates and voters focus. We need to do more to get folks seriously thinking about this.” Of Virginia’s 38 cities, only Alexandria and Richmond do not use staggered terms; 61 of Virginia’s 95 counties use staggered terms.

● [Insert your idea, and your commitment, here.]

Great article but I’m left with some questions. So what might those staggered terms look like? Do we elect 2 or more council members every year? Every two years? How often do we elect the mayor? How do we decide who is the vice mayor? Does that change after every election?

Our city is faced with a couple of generational cost issues that could be mitigated if our city had ANY desire to sponsor diversity of thought at a local or regional level.

You make some foundational points about this election, but to focus on local, we need money and the 2025-26 forecast will continue to increase taxes to pay for services and functions that are poorly managed or reported.

Staggered terms would suggest a few things:

1. The mayoral term needs to be longer

2. Keep 3 for six and run the other 3. This is the real conundrum. My 2¢, think outside the box. 32 precincts. If you assign each councilor 4 precincts, then you have 8 councilors. Wards can be staggered every 4 years. I would also advocate that these major elections should be on the “off” years of a Presidential election.

I’m happy to provide more ideas that help our community. I tried to discuss these and the significance of economic development in a Presidential election but my efforts were in vain.