Analysis: Why Election Reform is Elusive

Alexandria specifics to ponder when considering process changes. From The Alexandria Times, February 29, 2024.

City elections are inevitable and intermittent.

Improving Alexandria’s election process offers none of the satisfactions of infrastructure enhancements—plaques, ribbon-cutting ceremonies, better roads, etc. Election processes are usually discussed in subjective and predictive ways: “If we [insert potential reform], then that will have the [positive or negative] effect of [describe dramatic benefit or catastrophe.]”

Efforts to improve city elections are complicated by Virginia’s adherence to the Dillon Rule which mandates that localities can exercise only powers expressly authorized or delegated to them by the state. The Dillon Rule, from an 1868 Iowa case, compels the city to request passage of a “charter bill” by the General Assembly to approve, for example, election scheduling. For decades, City Council and School Board elections were held in May until the General Assembly authorized, at Alexandria’s request, elections in November.

Election improvement is not on most Alexandrians’ radar, so things go along as they always have. Over time, anomalies or oddities develop, for example, the concurrent election of the seven-member City Council including the mayor—and the nine-member School Board.

Attention span—the capacity of officials and residents to debate and resolve issues—is another complication. In 2023, the Zoning for Housing debate crowded out other issues. The entertainment and sports complex proposed for Potomac Yard may do the same thing in 2024. Finally, when and how city elections are held is of limited interest, except to politicians and municipal affairs nerds.

What follows explores the goals of election reform, the effects of rescheduling city elections from May to November, the roles of the political parties, what “nonpartisan” means, or should mean, and describes ways to potentially improve Alexandria’s elections.

The Democratic primary is June 18, and shouldn’t be confused with the March 5 primary which is just for the presidential election. The general election for both the presidential contest and local offices will be held on November 5, so it is timely to think about what is working well, and what might work better.

Local elections in May or November?

The last major change to Alexandria’s elections occurred in 2009 when city elections were moved from May to November to coincide with state and federal elections. Then-Councilor Justin Wilson—who had just lost his reelection bid in that year’s May election—said increasing voter turnout was the goal in shifting elections to the fall. He said:

Essentially, every three years, after we have another election and after the turnout gets ever lower, there’s a discussion among the community about what we can do, and one of the most popular solutions is to move it to November.

Holding city elections in November to promote a “good government” goal—increased voter participation—was also a way to gain partisan advantage. Wilson regained his seat on Council in 2012, the inaugural fall city election. November city elections cement Democratic party control because Democrats—the overwhelming Alexandria majority—turn out to vote for state and federal offices.

While one Republican and one Independent were elected in the last May election in 2009, not a single Republican has been voted onto Council or the mayor’s seat since the first November city election occurred in 2012. However, Election Day turnout as a percentage of registered voters increased in the three combined city, state and federal elections that followed.

Angie Maniglia Turner, Alexandria’s General Registrar and Director of Elections, said that the Alexandria Electoral Board does not track the number of voters for city offices separately from the voters for state and federal offices.

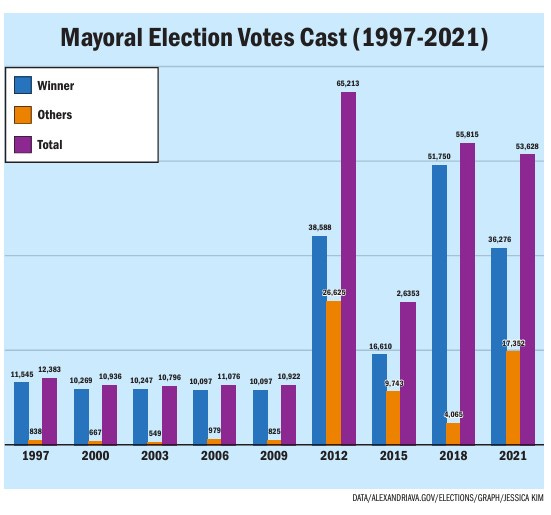

Even so, the vote totals for the office of Mayor of Alexandria are a reasonable proxy for voter participation in city elections. This chart shows the votes cast in city mayoral elections since 1997.

Alexandrians who go to the polls generally vote in the city elections, and turnout spikes in presidential election years. The increased turnout in local elections that coincide with state and national elections may be attributable, in part, to voters—aided by party-provided sample ballots—who are unfamiliar with local issues and cast straight party-line ballots.

Local Political Parties

The era of political party platforms for local issues seems to have passed. No Democratic or Republican positions have been evident on, for example, zoning, open space, transportation, public health or the schools. Councilor Alyia Gaskins said at the City Council’s October 21, 2023 town hall, “A pothole is neither Democrat nor Republican and it doesn’t matter in terms of your party affiliation to be able to fix the roads or fix the sewers.”

At the city level, political parties offer candidates for election and provide a form of tribal identity for potential voters: “I am a [Democrat or Republican] so the fact that [insert name of candidate] is a [Democrat or Republican] means that he or she thinks as I do so, so I can safely vote for him or her.” Local political parties also deliver information—campaign materials, advertising, etc.

Sort-of Nonpartisan City Elections

Like most municipal elections, Alexandria’s are nominally nonpartisan in that the ballot does not identify candidates’ party affiliations with an “R” or “D” or “I” after their names on the ballot as is the case in state and federal elections. Councilor Canek Aguirre said at the town hall, “When you go to vote for Council next year we won’t have letters after our names. That’s just what it is.” Other electoral activities, including candidate selection and the ballot format, are distinctly partisan or party-related.

The city’s nonpartisan-ish elections are designed to avoid the Hatch Act, the federal law that bars federal officials from running in partisan elections.

There is an Alexandria tradition that School Board elections be fully nonpartisan—candidates do not run with party identification and the political parties neither nominate candidates nor do they electioneer on their behalf. This aligns with the reality that there is no Republican or Democratic position, at least at the local level, on how to improve the schools.

Potential Improvements

Some potential reforms are substantial and would require Council and/or General Assembly approval and others could be implemented locally. Here are a few possibilities.

Stagger Terms of Office. In 2023, the School Board devoted substantial time and effort to investigating how staggered terms might work in Alexandria. This work followed up on discussions in 2019 and earlier that were sidelined by the pandemic. Staggered term advocates claim such a system promotes continuity and institutional memory. They also assert that campaign debate is more substantive when candidate forums are smaller and do not degrade into attention-getting displays because of the large number of candidates.

Election calendars published by the Virginia Department of Elections show that of the commonwealth’s 38 cities, two (Alexandria and Richmond) elect their city councils and school boards at one time while 36 employ staggered terms to elect both bodies. Of Virginia’s 95 counties, 34 elect their boards of supervisors and school boards concurrently and 61 use staggered terms.

The City Council has not taken a formal position on staggered terms, but a School Board member said that the Council’s informal message is, “Not now.” The October 2023 town hall revealed mixed reactions to staggered terms: Gaskins and Councilor Kirk McPike were “open to conversations” about staggered terms.

Councilor John Taylor Chapman was “against the School Board kind of leading the conversation on this issue.” He said at the town hall:

School Board members need to meet with all of us and talk to us about how messing with elections is going to help our children.

While School Board members are concerned about continuity, some councilors do not see turnover as a problem.

“So, my thing to them [the School Board] is run again, win your election,” Councilor Canek Aguirre said at the town hall, “The Council, all of us along with the Mayor, are up every single election, and there has been a lot of continuity on this Council for a long time.”

One of the arguments for deferring the city’s Zoning for Housing/Housing for All proposals was that these issues deserved to be debated in a campaign. Thus, the argument goes, in a staggered term system issues would be tied more closely to an imminent election.

Reduce the Size of the School Board. Alexandria’s 9-member School Board makes the city part of a distinct minority. A Virginia School Boards Association spokesperson said that only 11 of Virginia’s 131 school boards have 9 or more members.

Aguirre conditioned his interest in potential changes to election processes on reducing the number of School Board seats. At the town hall he said, “To me, it’s absolutely ridiculous that we have nine people on there and this is part of what leads to so much discontinuity and turnover. “

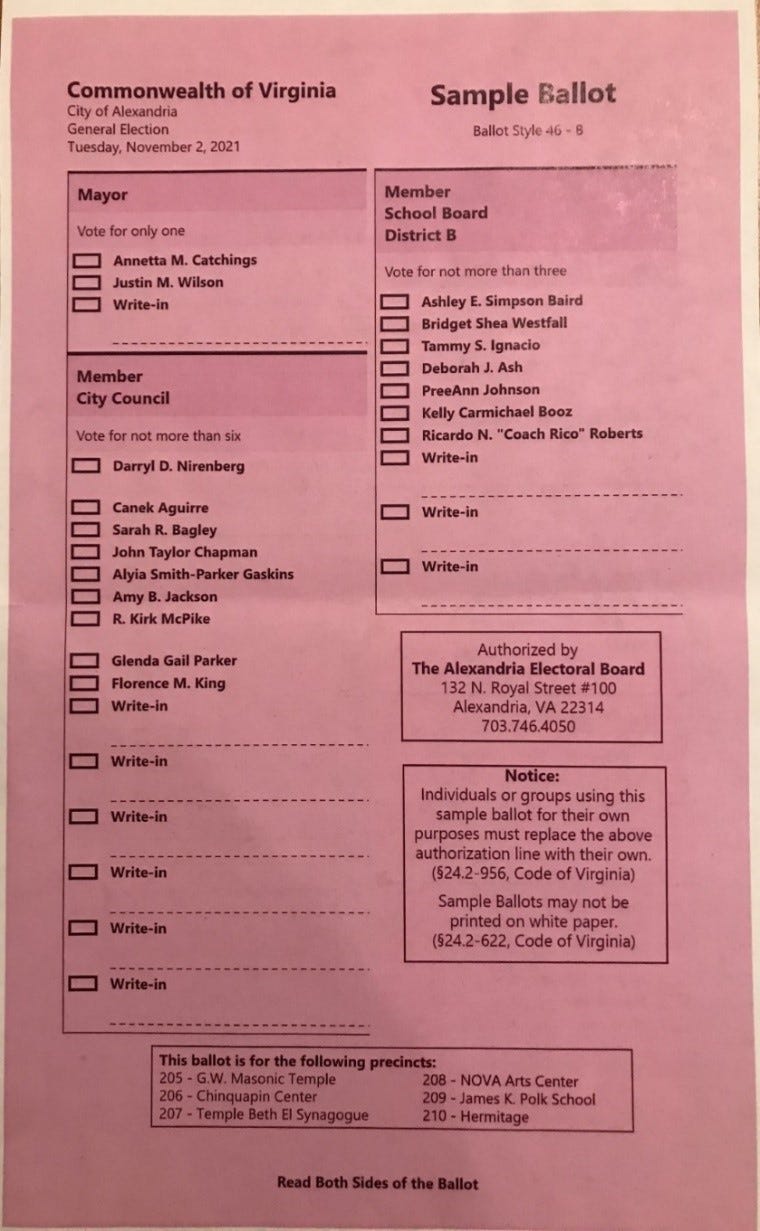

Change the Ballot. Section 24.2-613(C) of the Code of Virginia provides, “In an election district in which more than one person is nominated by one political party for the same office, the candidates shall appear alphabetically in their party groups under the name of the office, with sufficient space between the party groups to indicate them as such.”

In the 2021 election, the Electoral Board issued four ballots because of the city’s three school board districts and two General Assembly districts.

Here is how one of the city’s 2021 ballots presented the candidates:

Grouping candidates by parties on the ballot, but without a party designation, sends an important subliminal partisan signal. If a voter recognizes the party affiliation of one candidate in a group, then a party-line vote is easy. A less party-centric approach would be to list the candidates in alphabetical order or as determined by random selection.

Elect Candidates by Wards. Proponents of a ward system, or voting by district, assert that it would bring elected officials closer to the electorate. Opponents claim that a ward system would create divisions in the city and that Alexandria’s small size makes such a system unnecessary. Voting by wards in Alexandria was replaced with at-large voting in 1950.

Mayor Justin Wilson said that he was “not ardently opposed” to voting by wards but he believes that ward voting, “will not fix the problems that people think it will.” Wilson’s experience is that the main advocates for a ward system are residents disappointed with a land use decision or those who would like to see a Republican on the City Council. Wilson said that a councilor who voted to serve the interests of his or her ward on a land use issue might still be in a 6-1 minority. Wilson believes that it is probably impossible to configure a voting district in Alexandria dominated by registered Republicans because there are so few of them.

Old Town resident Michael Maibach has advocated extensively for Alexandria’s return to a ward system to elect the City Council. Voting by wards is “…fundamental to a republican (small ‘r’) form of government” said Maibach, “It divides majority power so it doesn’t overwhelm minority voices.” Maibach said that when a majority exercises control through at-large voting, “The Democrats will win every election, control every decision, and this leads to the temptation for corruption.”

Adopt Ranked Choice Voting. Ranked choice voting (RCV) allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. Arlington County was the first Virginia locality to adopt RCV. Arlington’s website says, “Ranked choice voting allows your vote to count towards another candidate if your 1st choice candidate receives the least amount of votes.”

RCV advocates claim that it promotes civil campaigning—candidates are less likely to trash each other—and yields a better result in elections that require the winning candidate to obtain a minimum percentage of the vote.

Arlington experimented with RCV in a primary election, but canceled it for the county’s elections last November over concerns about tabulation methods and the adequacy of public communications. According to The Washington Post, Arlington County Board Chair Christian Dorsey, a Democrat, said, “It’s pretty clear that we didn’t necessarily get all pockets of our community to view this in the same way.”

Alexandria voters already do something like RCV. The range of votes for the six successful Council candidates in 2021 (32,666 to 26,014) shows that voters do not use all their votes. The effect of this under voting or “bullet voting,” of course, is to increase the weight of the votes cast for the candidates who receive them.

Election processes do matter, and Alexandria might be well served if a community discussion results in adoption of some of the ideas proposed above. If politics, including local politics, is a form of theater, elections are the stage for the performance. If the staging improves, the performance should improve.

A return to separation of local and state/national elections was not considered as an option? As a relative of the last (forever?) Republican on the council I know that while he may have been on the wrong end of many 6-1 decisions, he at least gave voice to concerns of many citizens. To have Republicans dismissed "because there are so few of them" is disgraceful. Our local elections should be reserved for those who care enough to become informed and vote, not for those who simply follow the D. Many Republicans have served the Council with distinction over the years, and to exclude them forever is a loss to the city.