An Eminent Historian's Masterwork

Professor Richard Slotkin's book, A Great Disorder, explains the significance of narratives and myths in America's past and present

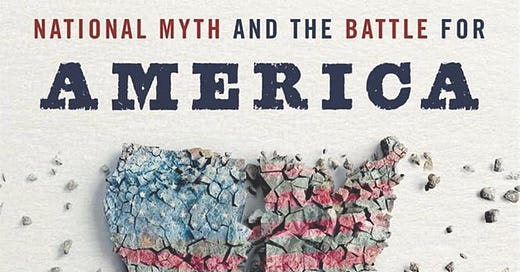

In A Great Disorder—National Myth and the Battle for America Wesleyan University Professor Richard Slotkin chronicles the uses and abuses of American historical myths to help us understand where we are today. Our national circumstances seem increasingly perilous after last week’s debate between President Joseph Biden and former President Donald Trump and this term’s Supreme Court decisions.

The book traces four myths that Slotkin calls, “the most crucial to Americans’ under-standing of what their nation is, where it came from and what it stands for.” (12) [These are the Myth of the Frontier, the Myth of the Founding, three different Myths of the Civil War, and the Myth of the Good War. The March 4, 2024 review of the book in The New York Times can be seen

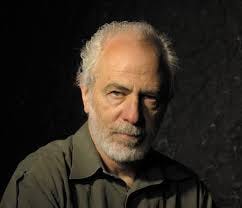

Slotkin, an expert on the impacts of literature and popular culture on American politics and character, is best known for trilogy of books on how myth, particularly the Myth of the Frontier, affected America’s development as a nation. Two books in the trilogy, Regeneration Through Violence; The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 and Gunfighter Nation, were finalists for the National Book Award. Slotkin has also written several novels including Abe, which imagines a young Abraham Lincoln, and The Crater, a novel about the explosion of a huge mine under the Confederate trenches in 1864 at Petersburg, Virginia.

I was very fortunate to take classes with Slotkin at Wesleyan in the early 1970’s. I was a naïve and callow college student. He was then in the early stages of a brilliant career at Wesleyan. In class, he was mesmerizing and challenging. He taught at Wesleyan from 1966 to 2009, ultimately retiring as the Olin Professor of English and American Studies, Emeritus.

I inherited an interest in American Studies—the examination and analyses of American history, literature, art and popular culture. My father returned from combat duty in the Italian campaign in World War II with the Army’s Tenth Mountain Division to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1951 in what was then known as American Civilization. He was a historian on the faculty of the University of Michigan for 38 years.

A Great Disorder describes the historical origins of each essential American myth so that we may “fully understand the charge that each myth carries.” (12) The origins and uses of America’s foundational myths relate directly to how these myths are used in today’s fractious politics.

Slotkin has an exceptional command of American history and culture. The book is clear and insightful on everything from James Fennimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales to the Lincoln-Douglas debates to Hollywood’s platoon movies. An astute friend recently described A Great Disorder to me as, “The book I would recommend if someone wanted one book that explained the Red/Blue divide in American culture and politics.”

A Great Disorder, at 417 pages with extensive notes, presents comprehensive analyses of American narratives and how those narratives become myths and how those myths have been used in our culture and politics.

For example, Slotkin traces the origin of the Lost Cause myth to an 1866 book, The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates by a Richmond editor, Edward Pollard. Slotkin says:

Pollard held that the South had been entirely within its rights in seceding, and that slavery had been a benevolent and productive institution. He blamed defeat on the North’s material advantages, its ruthless destruction of Southern property—and mismanagement by the Davis administration and certain Southern generals. Implicit in that last idea is a might-have-been: if the war had been better managed, the Confederacy might have won. (90)

Slotkin describes how useful the Myth of the Lost Cause has been to Donald Trump, who he describes as “the last President of the Confederacy” in part because of, “…his decision to become the chief defender of Confederate symbolism.” (354) Slotkin argues:

Trump thus made the content and meaning of America’s national myths an explicit campaign issue, and a centerpiece of his program for restoring American greatness. He would follow the Lost Cause paradigm, emphasizing the need for extreme and violent means to redeem an imperiled civilization, and he chose this over the themes of economic prosperity and “toughness” on international trade that advisers like Larry Kudlow and Stephen Moore wanted to make the basis of the campaign. (355)

MAGA, then, is a Lost Cause-derived myth of longing for what was and what might have been. And, like the Myth of the Lost Cause, MAGA readily embraces violence to redeem the culture and ideals that were supposedly lost by “real” Americans to alien populations.

Every page of A Great Disorder is informative, but the most compelling and immediate section of the book is the extended Conclusion titled National Myth and the Crisis of Democracy. The Conclusion is really an essay on how to deal with MAGA’s political and cultural appeals that are embedded, “…in a narrative that connects its adherents to the major American national myths and gives them the exhilarating sense of riding a wave of historical destiny.” (397)

Slotkin’s view is that myth turns history into symbols for actual use and he describes the challenge to those outside MAGA this way:

Thus the task facing the blue coalition is not just to enact policies but to combine political action with cultural reframing to convince a skeptical public that the federal government can be a force for meaningful change. Since the 1970s the Left and center Left have failed to formulate a coherent version of the American future, or a version of national myth that would root their program in historical tradition. (399)

Slotkin asserts that if Trump wins a second turn, “the damage to republican institutions and the national interest might well be irreparable.” (415) He calls for vastly expanded grassroots organizing focusing on “issues that go to the heart of reform” such as racial justice, voting rights, gun safety, workers’ rights, the preservation of democracy, women’s rights and climate change. These efforts, Slotkin says, “will have to be made to meet people where they are and reopen lines of communication within and between communities” in, for example, town and city meetings and proceedings.

He observes:

MAGA’s problem is that it can rule, but it cannot govern: it can use the instruments of law and government, the dictates of a conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court, and vigilante intimidation to impose a degree of obedience. But its theory of politics precludes the possibility of working with the opposition toward mutually acceptable policies. Thus it cannot create a stable political order, such as the New Deal and neoliberal orders were in their time. (415)

This essential, and easy to miss, insight derives from facts that are right before us: every MAGA-sponsored government initiative or proposal is either subtractive (reproductive rights) or a mandate (mass deportation, border walls, tariffs). The essence of MAGA is, as Slotkin argues, a great disorder.

A Great Disorder is not light reading, but its rewards are abundant.

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] All page citations are to A Great Disorder.

Special thanks to Allen Yale for assistance with this post.

First of all, your review is very compelling and makes me want to read the book. As someone interested in American History, I search for lessons of the past to explain the present (and future? shudder...) phenomenon of Trump. I'm not convinced the Lost Cause of the Confederacy explains it--but that's why I need to read the book! My interest in the phenomenon has led me to non-academic historian Eric Larson's latest book, "The Demon of Unrest." Larson's horror at the events of 1/6/21 led him to examine the period after Lincoln's election and before Lincoln's inauguration four months later, the period during which the Southern states seceded. The parallels between 1860 and today's red/blue divisions are stunning. Finally, I have to add that anytime I read the word "callow" I think of "The Fantasticks." and its song "Try to Remember." It might be a good time for a reprise of "The Fantasticks" on Broadway as life as we have known it, where civilized political behavior rules the day, continues to fade away.