The Best of What's Around: A Senior Thesis Describes Alexandria's Struggle for Racial Justice

Griffin Harris details the crosscurrents and paradoxes of a turbulent period in the city's history

According to Alexandria’s Planning and Zoning Department, every five years about 27% of the city’s residents, or over 40,000 people, move in or out of the city. Data nerds can contemplate the city’s demographic characteristics on Census.gov

Alexandria’s colonial-era history is commemorated in historic buildings, plaques and markers, and museums. In a city where nearly a third of the residents move every five years the history of more recent times can be overlooked. In Washington’s Shadow: Race, Class, and Neighborhood in Alexandria, Virginia, 1950-1970, Northwestern University graduate Griffin Harris’ deeply researched and very readable senior thesis provides a compelling portrait of Alexandria in a turbulent time.

Harris, an Alexandria native and graduate of the former T.C. Williams High School, won the Northwestern History Department’s 2023 prize for his thesis about Alexandria’s long struggle with the changes compelled by the Civil Rights movement and Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court case outlawing public school segregation. The thesis can be read

Harris focuses on, “…the collision of racial attitudes between the town’s diverse political factions, focusing chiefly on the issues of school desegregation and urban renewal.” (ii)[1] He asserts that Alexandria, which did not experience rioting and violence as intense as, for example, Newark or Detroit, was one of the cities that “defined the center” without a city-wide consensus about integration:

By following the factional disputes that animated Alexandria, this thesis shows the vulnerability and fragility of suburban racial moderation, demonstrating that postwar suburban politics was more complicated and more contested than the existing literature suggests. (7)

In Washington’s Shadow explains, “[W]hen desegregation did finally happen, it represented not just a transition in [Alexandria’s] politics, but in its very identity—from southern port town to middle-class suburbia.” (13)

A Diverse Cast of Characters

The best historical accounts bring alive those people who made history happen and In Washington’s Shadow passes this test easily. On the segregationist side, Harris describes the almost total control over Virginia politics exercised by the Byrd machine headed by Governor, and later Senator, Harry F. Byrd, Jr. The machine’s operatives included Byrd’s cousin, segregationist Alexandria Mayor Marshall Beverly, and Byrd’s brother-in-law James Thomson, a General Assembly power for many years.

The thesis describes the efforts and trials of Black Alexandrians such as Otto and Samuel Tucker, Ferdinand Day, Marion Johnson and Melvin Miller who collectively had to decide when, how, and how hard to confront the Alexandria establishment they were gradually joining.

In the public schools, segregationist high school Principal T.C. Williams was part of a culture that ultimately gave way to the “triumph of racial moderatism” (77) represented by Superintendent John C. Albohm. In Harris’ telling, Albohm “practiced a skillful form of retail politics as a regular presence at meetings of PTAs and civic groups, in living rooms and church basements.” (75)

Harris points out that Alexandria’s divisions were revealed in the 1963 election when the voters sent two veteran politicians to the House of Delegates. One was the arch-segregationist Thomson; the other was Marion Galland who had been the president of the League of Women Voters for most of the 1950s and, “a leader of the white moderates’ opposition to massive resistance.” Galland’s platform included increasing public school spending and abolishing poll taxes. (77)

The End of Mudtown

Harris describes the complicated issues that resulted in the razing of the historically Black Seminary neighborhood in the city’s center. The neighborhood’s name related to the number of residents who worked at the nearby Episcopal seminary. As one of the last areas in the city to have paved streets, the area was derogatorily known as Mudtown.

Some called the redevelopment of the approximately 30 acres in the city’s center into Chinquapin Park, and the site for the city’s new high school, urban renewal. Others termed it “Negro removal.” The process was enormously difficult. Miller and Johnson were involved negotiations beginning in late 1960 that culminated in the approval of the Mudtown Urban Renewal Project in February 1963. (72)

The compromise resulted in the construction of T.C. Williams High School, later renamed Alexandria City High School. Seven acres were reserved for the construction of new houses for families who had owned property in the Seminary neighborhood.

Armistead Boothe’s Delicate Balancing Act

Nobody walked a finer line than lawyer Armistead Boothe who was first elected in 1948 as a delegate to the General Assembly. Boothe, a native Alexandrian, saw that days of segregated schools were limited. Harris says:

Boothe’s approach to school segregation reflected neither the principled demands for racial equality endorsed by a minority of Virginians—Black Virginians, of course, but also a handful of white liberals—nor the strident racism espoused by the vast majority. Instead, he offered ardent pragmatism, vigorously trying to define and defend a fragile position at the center of the political spectrum. (22)

In 1954, Thomson was elected to Boothe’s seat in the House of Delegates when Boothe was elected as a state senator. Segregation advocates organized a state-wide referendum that year to repeal mandatory school attendance and amend the constitution to facilitate public grants for families who wished to send their children to private segregated schools. Thomson told his supporters, “When you go to the polls vote for segregation.” Harris observes, “It was a testament to the ideological crosscurrents pulling on Alexandria that the same voters, in the same year, elected men with such divergent views.” (28)

Armistead Boothe Park is in the Cameron Station neighborhood. The city’s website says:

On June 13, 2000, the Alexandria City Council approved the naming of the west end park at the former U.S. Army base at Cameron Station in honor of the late Armistead L. Boothe. A native Alexandrian, Boothe served as a special assistant in the United States Office of the Attorney General from 1934 to 1936 and as City Attorney of Alexandria from 1938 to 1943. He was a strong supporter of public school integration in the 1950s.

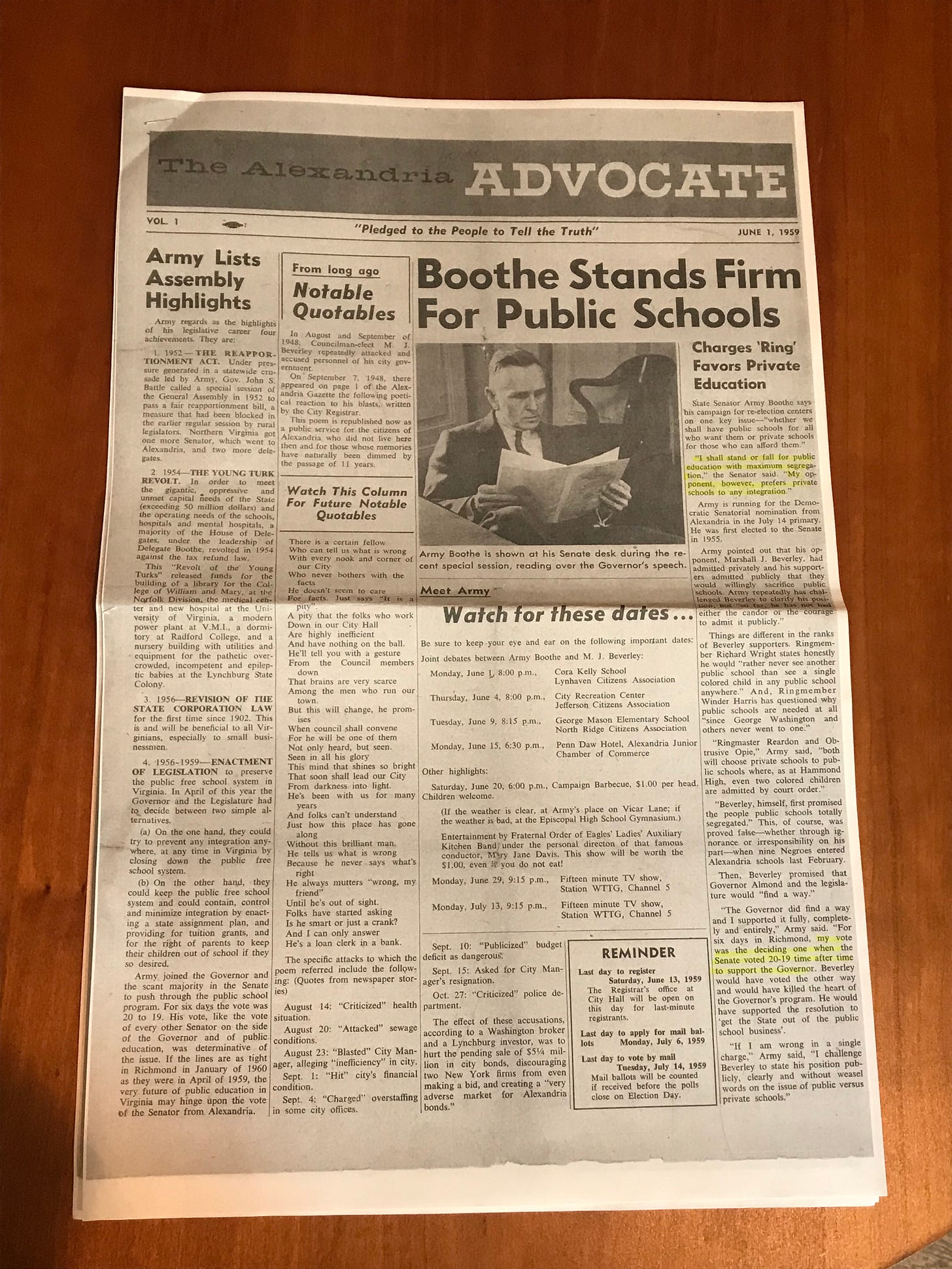

Boothe lost his last electoral run, a 1966 primary campaign against Harry Byrd, Jr. His 1959 campaign materials included a brochure in the form of a newspaper, The Alexandria Advocate, with articles about Boothe’s achievements, his platform, and poetry.

Here it is:

The lead article, titled “Boothe Stands Firm for Public Schools,” begins:

State Senator Army Boothe says his campaign for re-election centers on one key issue—“whether we shall have public schools for all who want them or private schools for those who can afford them.”

“I stand or fall for public education with maximum segregation,” the Senator said. “My opponent, however, prefers private schools to any integration.”

The Alexandria Advocate says, “…the truth, the whole truth and the brief truth about Army Boothe’s position on public schools, is as follows:”

1956-1958—Army voted for all bills and resolutions including interposition to preserve segregation in the public schools except bills closing public schools and cutting off state funds to the localities.

***

1959—Army supported fully the report of the Perrow Commission and the program of Governor Almond…In the Senate where the vote was 20 to 19 on the key issues involved, his vote was the single determining vote in putting through the Governor’s program and in killing the attempt of the resistors “to get the State out of the public school business.”

The Alexandria Advocate summarizes Boothe’s public education position this way:

Under the present state plan, for which Army voted:

1. The state public school system is maintained.

2. The public schools of Virginia will remain at least 99% segregated for an indefinite time.

3. No locality will be compelled to operate public schools against its will.

4. No parent will be compelled to send his child to an integrated school against his will.

Was Boothe a “strong supporter of public school integration” as described in the city’s description of the park named for him? The views on race and integration that dominated Boothe’s time in public life were intensely held. That Boothe is seen by some today as a moderate pragmatist is a reminder of the intensity of racism’s entrenchment.

It is easy to forget that the centerpiece of massive resistance—the idea making it “massive”—was the indefinite closing of Virginia’s public schools. Boothe stood against that. Even so, he supported integration, five years after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, only to the minimum extent possible. It took court rulings to make more than token integration a fact of Alexandria life.

Harris illuminates these and other fascinating events and paradoxes in a thesis that is essential reading for anyone interested in the city’s history.

Special thanks to Cindy Anderson for help with this post.

[1] All page citations are to In Washington’s Shadow: Race, Class and Neighborhood in Alexandria, Virginia, 1950-1970.