Going to the Movies: The Marx Brothers and "Duck Soup"

An election special on how a classic movie comedy explains authoritarianism and its practitioners

Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly and applying the wrong remedies. –Groucho Marx

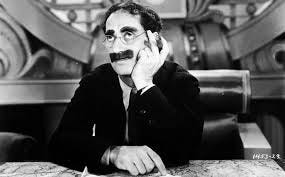

Groucho Marx’s skeptical view of politics is evident in his role (President Rufus T. Firefly) and those of his brothers, Harpo (Pinky), Chico (Chicolini) and Zeppo (Lt. Bob Roland, Firefly’s Secretary) in Duck Soup (1933), their timeless movie satire on authoritarian politics and war.

Their last movie for the Paramount studio, and the last movie in which all the scenes directly involved one or more of the Marx Brothers, Duck Soup is on the National Film Registry and ranks fifth on the American Film Institute’s 100 Years...100 Laughs funniest movies list. You can see the list

The movie is a fixture on other “Best Movies” lists more than 90 years after its release.

Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Zeppo[1] honed their performing skills under the watchful direction of their stage mother, Minnie, in live performances in vaudeville. Duck Soup, their fifth movie, clocks in at a crisp 70 minutes.

In his book, The Great Movies, critic Roger Ebert describes the brothers’ origins and influence as performers:

Movies gave them a mass audience, and they were the instrument that translated what was once essentially a Jewish style of humor into the dominant note of American comedy. Although they were not taken as seriously, they were as surrealist as Dali, as shocking as Stravinsky, as verbally playful as Gertrude Stein, as alienated as Kafka. Because they worked in the genres of slapstick and screwball, they did not get the same kind of attention, but their effect on the popular mind was probably more influential. ‘As an absurdist essay on politics and warfare,’ wrote the British critic Patrick McCray, ‘Duck Soup can stand alongside (or even above) the works of Beckett and Ionesco.’ (160)

What is Duck Soup About?

The plot of Duck Soup is almost incidental. Briefly, heiress Mrs. Teasdale (Margaret Dumont) has given the small, vaguely European, country of Freedonia $20 million (over $468 million in today’s dollars) from her late husband’s estate. When she is asked for more money, Mrs. Teasdale, smitten with Firefly, insists that that he become Freedonia’s President. Scheming Ambassador Trentino (Louis Calhern) of neighboring nation Sylvania is Firefly’s rival for Mrs. Teasdale. Trentino hires the hilariously incompetent Pinky and Chicolini to spy on Firefly and lay the groundwork for Sylvania’s conquest of Freedonia.

Duck Soup, with Freedonia’s echoes of the German and Italian regimes of the 1930’s, does not involve a compelling narrative—the plot functions mostly to show off the substantial and varied talents of each Marx brother.

Why Should We Watch Duck Soup?

Stefan Kanfer, in his biography, Groucho—The Life and Times of Julius Henry Marx, observes that Duck Soup “contains a cynicism so mordant and a pace so modern that it reaches beyond its time to join the classics of political satire.” (173) Kanfer observes that Duck Soup stresses director Leo McCarey’s central idea, “Do it visually” which means “…filling every scene with sight gags that make Groucho work harder for his laughs.” (173)

Duck Soup was shot in black-and-white which emphasizes the sheen of its elaborate Art Deco sets that include columns, staircases, uniformed trumpeters and sword-bearing soldiers, and ballerinas strewing flower petals. Duck Soup’s effective send-up of the theatrical aspects of politics and government make us look again at how events such as rallies and political conventions are staged.

In this scene, the elaborate set, movement of the actors, and rapid-fire gags introduce Groucho as Firefly. He awakes, fully clothed, and arrives at the “mammoth reception” (as the newspapers stills in the movie call it) in his honor by sliding down a fire pole, a scene viewable

Money Talks: Authoritarianism and Donor Class Transactions

Firefly is elevated to power by Mrs. Teasdale, a member of Freedonia’s ruling class. Duck Soup confirms that the donor classes of the Right (Adelson, Koch) and the Left (Hollywood, Soros) are essential to attain political power. By attributing Firefly’s rise to Mrs. Teasdale’s money, the movie emphasizes the transactional aspects of authoritarian politics: Mrs. Teasdale gives Freedonia a huge amount of money so she is empowered to select Firefly as Freedonia’s leader.

Other authoritarians have shown an instinct for politics as a series of financial trades. Vladimir Putin’s power derives in part from the economic benefits he confers on (or withholds from) Russia’s oligarchs. Donald Trump has encouraged oil company executives to give vast amounts of money to his presidential campaign in return for a pro-fossil fuel energy policy. According to The Wall Street Journal, oil companies and their executives have contributed more than $16 million since last October to Trump-aligned committees and the Republican National Committee. [2]

A Sublime Parody of Authoritarian Political Leaders

Firefly shows characteristics and values evident in the authoritarian leaders of our time. He is devious, has near-manic energy, and is totally self-focused. Freedonia’s future as a nation hardly concerns Firefly.

Firefly unleashes a torrent of insults on everyone around him and especially on women. Mrs. Teasdale tells him, “I sponsored your appointment because I feel you are the most able statesman in all Freedonia.”

Firefly, like other authoritarians, loves flattery. He responds, but with a typical Groucho twist:

Well, that covers a lot of ground. Say, you cover a lot of ground yourself. You’d better beat it. I hear they’re going to tear you down and put up an office building where you’re standing. You can leave in a taxi. If you can’t get a taxi, you can leave in a huff. If that’s too soon, you can leave in a minute and a huff. You know, you haven’t stopped talking since I came here. You must have been vaccinated with a phonograph needle.

Mrs. Teasdale (Dumont, an exceptional foil for the Marx Brothers) affirms Duck Soup’s absurdity when she ignores Firefly’s insults. She tells him, “The future of Freedonia rests on you.” Groucho’s greasepaint eyebrows and mustache supercharge his facial expressions.

Like many authoritarians, Firefly is self-absorbed, but open about his drastic plans for the nation. Those plans follow the authoritarian model of centralized control and limited personal freedoms. Firefly sings, “If any form of pleasure is exhibited, report it to me and it shall be prohibited.” Duck Soup shows that authoritarian politicians are less concerned with the quality of national life than they are with self-aggrandizement.

Thus, the paradox of authoritarianism is clearly shown. Firefly, and other authoritarian leaders, can rule. However, their disinterest in the mechanics of government, self-focus, and a political style based on hatred of the opposition preclude them from governing effectively.

Tellingly, authoritarian leaders—Hitler, Mussolini and their modern counterparts—are both humorous and humorless. They can be successfully parodied in Duck Soup or Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) or on Saturday Night Live, but they have no sense of humor themselves. This central aspect of the authoritarian identity obscures the unpredictability and danger of authoritarian leaders.

Gaslighting: Who You Gonna Believe, Me, or Your Own Eyes?

One of the hallmarks of authoritarian regimes, and politicians in trouble, is gaslighting, or psychological manipulation designed to make us doubt our accurate perceptions of reality. The determined and repeated denial of obvious facts has been applied to inauguration crowd size (Donald Trump), the severity of a pandemic (Donald Trump), the purpose of an attack on the United States Capitol (Donald Trump and others), the reasons for invading a neighboring nation (Vladimir Putin) and the increasingly pronounced limitations and infirmities that come with life at age 80 and beyond (until July 20-21, 2024, Joe Biden).

Duck Soup shows how gaslighting works in a scene in which Chicolini (Chico Marx with his Italian accent) is disguised as Firefly. Mrs. Teasdale sees Firefly, in his night dress, leave their room. She then sees Chicolini dressed as Firefly. Confusion ensues in a scene viewable

Who you gonna believe, me, or your own eyes? is a defining question for our politics. In a democracy subject to a constant stream of spin and disinformation accelerated or abetted by social media, our obligation is to sharpen our vision and ground our beliefs in objective facts.

How Authoritarianism, and One Man’s Compulsions, Start a War

The most compelling scene in Duck Soup may be when Firefly and Freedonia pivot astonishingly quickly from international politics to certain war. Sylvania’s troops are about to land in Freedonia. Mrs. Teasdale, “on behalf of the women of Freedonia,” has made one last effort to prevent war. She implores Firefly to meet with Trentino. At first, he agrees and promises to offer Trentino, on behalf of Freedonia, “the right hand of good fellowship.”

Then, in about a minute, Firefly constructs his own reality premised on the fear or assumption that Trentino might refuse to shake his hand. When Trentino arrives, Firefly slaps him for refusing his imagined handshake and commits Freedonia to war with Sylvania. The treacherous path to international conflict is viewable

The satire crystalizes the central element, and danger, of authoritarianism or any political system that vests enormous power in one person: a nation or nations can be seriously damaged or immobilized by that person’s insecurities, imagination, and compulsions. [3]

A Fine Reading Companion to Duck Soup

Humorist Roy Blount Jr.’s 2010 book, Hail, Hail, Euphoria: Presenting the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup, The Greatest War Movie Ever Made reads like watching Duck Soup with a knowledgeable friend and exceptional storyteller. Blount starts his short (145 page) book with, “But I’ve got Duck Soup up on the upper left corner of my computer monitor here, and I can fill you in on some background as we watch it together.”

Blount’s appreciation of Duck Soup is filled with inside information. He describes how Leo McCarey came to direct the movie, who really wrote the screenplay, how Groucho developed his slouching and scooting walk, and examines whether Margaret Dumont was in on the Marx Brothers’ jokes.

Blount observes, “In Duck Soup they [the Marx Brothers] manage to have it both ways—they are solidly in charge, yet thoroughly insurgent. Maybe that combination of rooted and rebellious is, or was, the American dream.” (137) This insight captures an essential aspect of authoritarianism: an authoritarian seeks extensive central control of the machinery of government while assuming an insurgent identity. Donald Trump’s promises to “drain the swamp” and eliminate the “deep state” while centralizing power in a White House staffed by people of unquestioning loyalty to him are a prime example.

A Few Final Words

Thank you for reading this far. Duck Soup is worth watching for its abundant laughs. The movie, and the Marx Brothers, have much to tell us about politics and the nature of authoritarianism.

Your comments are very welcome.

[1] A fifth Marx brother, Gummo, left the act when he was drafted into the Army in 1918 and was replaced by Zeppo. After World War I, Gummo became a successful businessman and theatrical agent.

[2] “Oil Billionaires Bet on Trump’s Energy Agenda,” The Wall Street Journal, July 25, 2024, p. A5; “Oil Lobbyists Draft Plans Targeting Climate Rules,” The Washington Post, October 20, 2024, p. G1.

[3] In Horsefeathers, a 1932 comedy set on a college campus, Groucho plays Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff, the new president of Huxley College. The movie illustrates another authoritarian theme—reflexive opposition to new ideas or to concepts “not invented here”—when Wagstaff sings “Whatever It Is, I’m Against It.” You can see it

Special thanks to Mark Freund and Trice Koopman for assistance with this post.

Thank you for reminding me about how timely and great this movie is. Hail Hail Freedonia!

Great post! My brother and I watched all the Marx Brothers movies as kids--probably explains a lot. "Duck Soup" and "Night at the Opera" were the best--as in funniest, as in most laughs per minute.